Contents

Introduction by Billy Reed

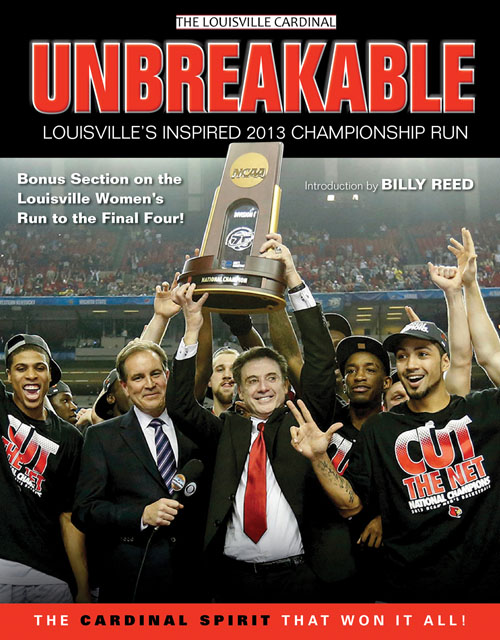

Americas Team Finds the Will to Win Louisvilles Third National Championship

Pitino Melds a Mosaic of Talents, Skills and Backgrounds En Route to an 82-76 Win over Michigan

This is the enduring image of the 2013 NCAA mens basketball tournament: Louisvilles Luke Hancock cradling the head of Kevin Ware in his arms and saying a prayer in the immediate aftermath of the most horrific injury in tournament history. It happened when Ware, flinging himself skyward while attempting to block a Duke players shot, came down wrong on his right leg, causing the femur to snap and puncture Wares skin. As soon as they saw it, Wares teammates either recoiled in horror or fell to the floor, wailing and weeping.

Except, that is, for Hancock. As the arena went silent and even the CBS announcers were almost too shocked to talk, Hancock prayed in Wares ear. A student manager draped a towel over the shattered leg to block it from view. Hearing Hancock, Ware reached deep into his soul and found a kind of grace that defies explanation. Even as he was going into shock, he urged his teammates to not worry about him, to carry on, to win the Midwest Regional championship and the ticket to hoops heaventhe Final Four in Atlanta. And so they did. They wiped away their tears, pulled tightly together and blew out the mighty Blue Devils in the second half.

It went largely unnoticed that Ware is black and Hancock white. But for basketball fans old enough to have a sense of basketballs history and sociology, the Hancock-Ware tableau was symbolic. Throughout the history of the NCAA tournament, which celebrated its 75th anniversary this year, only a few champions have carried the name of a city instead of a state or, in the case of Georgetown University, a neighborhood. Forget UCLA and UNLV, which were the local branches of larger state university systems. The city schools that have won titles are City College of New York, San Francisco, Cincinnati, Loyola of Chicago, Syracuse, and, of course, Louisville.

In their home states, urban universities often get short shrift from the legislature and are considered to be second-class citizens by the public. In the late 1980s, for example, former Kentucky coach Eddie Sutton, ignoring the championship Cardinal teams coached by Peck Hickman and Denny Crum, dismissed U of L as little brother. But what Sutton either didnt knowor chose to ignorewas that U of L and the other urban universities have made contributions to sports and society that were far more important than anything that happened on the floor.

Rick Pitino, the only head coach to win national championships with two different NCAA teams, holds the trophy aloft. (Austin Lassell/The Louisville Cardinal)

Every time significant strides have been made in integration, urban universities have been in the forefront. San Francisco became the first integrated champion in 1955, Cincinnati the first to start three African-American players in 1962, and Loyola the first to start four blacks in 1963. When Hickman and assistant John Dromo recruited U of Ls first African-American players in 1962, it made U of L the first predominantly white university in the statethe first south of the Mason-Dixon Line, according to some accountsto integrate its program. This is a proud heritage of which Kevin Ware and Luke Hancock probably were unaware when they transferred from Tennessee and George Mason, respectively, to play for Rick Pitino, the native New Yorker who had won the 1996 national title at Kentucky and who also was the first coach to take three programs (Providence, UK and U of L) to the Final Four.

When they arrived at U of L, they found Pitino building a team not from one-and-done future NBA stars, but from players who had different backgrounds and skill levels. Sure, some had pro bodies and pro ambitions, such as forwards Wayne Blackshear and Chane Behanan. But there also was Stephen Van Treece, a 6-foot-9 player with marginal D-I skills. The teams core consisted of Gorgui Dieng, a stoic 6-foot-11 center from Africa who could speak five languages; Peyton Siva, a slight point guard from Seattle who was so nice it was impossible to hold his trespassesturnovers, if you willagainst him; and a free spirit from Brooklyn whom Pitino called Russdiculous because of his penchant to put up shots that defied logic, not to mention the laws of gravity.

From the time Russ Smith arrived on campus, the mental tug-of-war between player and coach provided plenty of fascinating fodder for the talk shows and the fans. They truly seemed to have the sort of love-hate relationship that only a couple of New Yorkers could understand. Watching on TV back home in Queens, Smiths high school coach, the beloved Jack Curran of Archbishop Molloy, could only shake his head. Timeouts, [Pitino] is always yelling at Russ, Curran told Sports Illustrated early this season. And Russ puts his face right into Pitinos face. Like a soldier, he stands there. Hes almost touching noses with him. Hes very sober-looking while making believe that hes listening.

If Smith began to come around as the season unfolded, making better choices and become more team-oriented, his transformation became complete when he arrived in New York for the Big East Tournament in Madison Square Garden and learned that Curran had died unexpectedly of a heart attack. He dedicated his play to Curran and his teammates rallied around him, rolling to the tournament championship. In the title game against Syracuse, U of L trailed by 16 in the second half, only to have Smith, Silva and Ware ignite a second-half explosion in which they blew past the Orange and pulled away almost before Coach Jim Boeheim was able to work up one his famous scowls.

Still, though, the Cards didnt become Americas Team until the Ware tragedy. Because it happened before the CBS cameras in one of the tournaments most anticipated games, people around the globe became caught up in the sheer horror of the injury and the courageous way Pitino and the Cards responded. Suddenly the urban university from Louisville was feeling love it had never before received. Suddenly everyone became curious about the urban university located practically next door to Churchill Downs, home of the Kentucky Derby, and the changes that had been wrought since Tom Jurich became athletics director in 1998.

Guard Kevin Ware, an inspiration for the teams Final Four run, cuts down the nets despite being limited on crutches. (Austin Lassell/The Louisville Cardinal)

In the 15 years of the Jurich era, new arenas and stadiums have been built for every varsity sport, transforming the formerly drab campus into something vibrant and pleasing to the eyes of the millions who drove past every day on I-65. He also hired coaches who built teams that were nationally competitive in every sport. And most importantly, he insisted on full compliance with the NCAA rules and the provisions of Title IX. When plans were being made for the state-of-the-art KFC Yum! Center on the banks of the Ohio River, Jurichs main requirement was that the womens basketball team have a dressing room and practice court that was identical to the men.