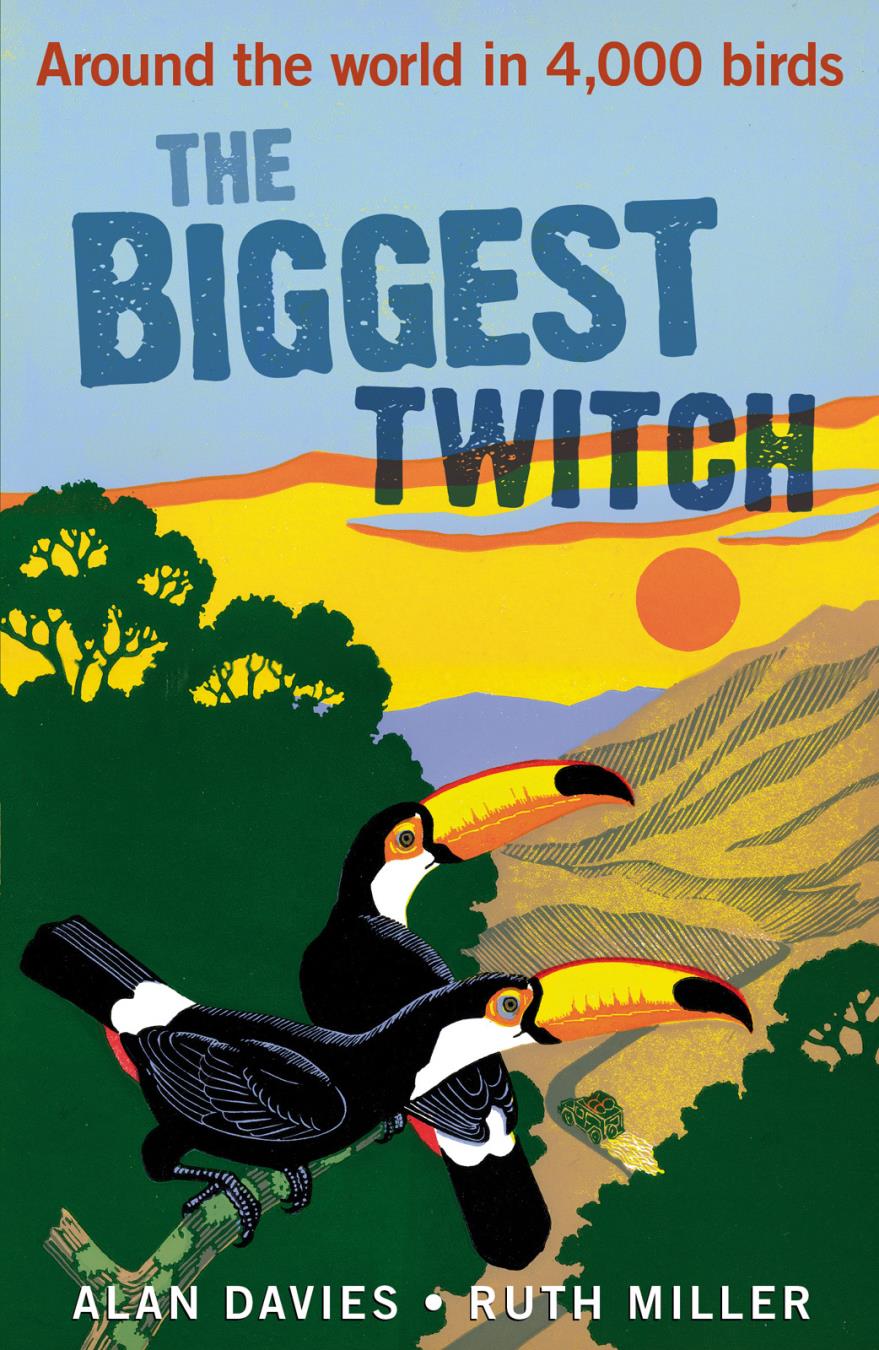

THE BIGGEST TWITCH

Birding is hunting without killing, preying without punishing, and collecting without clogging your home.

Mark Obmascik

This book is dedicated to Cecile Miller, without whose enormous generosity The Biggest Twitch would never have been concluded. Not only did she ensure the success of The Biggest Twitch, but she also had a major part in supplying half the personnel! We are forever grateful.

We also wish to thank Iain Campbell, once described as a manic genius, who is perhaps the person most responsible for our year of non-stop birding; a better friend would be impossible to find.

The list of birds seen on The Biggest Twitch in 2008 was based on the 2007 edition of The Clements Checklist of the Birds of the World. However, for ease of reading, the species names in the book are those commonly used in the relevant field guides. A full list of species seen is available on our website, www.thebiggesttwitch.com.

THE BIGGEST TWITCH

ALAN DAVIES AND RUTH MILLER

CHRISTOPHER HELM

LONDON

Published 2010 by Christopher Helm, an imprint of A&C Black Publishers Ltd.,

36 Soho Square, London W1D 3QY

www.acblack.com

Copyright 2010 by Alan Davies and Ruth Miller

eISBN: 978-1-4081-3404-7

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means photographic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage or retrieval systems without permission of the publishers.

This book is produced using paper that is made from wood grown in managed sustainable forests. It is natural, renewable and recyclable. The logging and manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

Commissioning Editor: Nigel Redman

Project Editor: Jim Martin

Copy Editor: Mike Unwin

Design by Mark Heslington Ltd, Scarborough, North Yorkshire

Cover artwork by Robert Gillmor

Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Books Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Seen from the outside, a birders preoccupation with lists would be easy to misinterpret. I have heard it said that we reduce birds to mere numbers, checking them off so well never have to look at them again. But most of us love seeing birds over and over. Otherwise it would be hard to explain the popularity of year lists.

I have been birding almost my whole life, and almost every year on the first of January I feel the urge to start a list for the new year. Its a way of appreciating the birds all over again: yesterday that bird was just another robin or sparrow, but today its a new one for the annual tally. As the year goes on, the list furnishes an excuse for getting out. Maybe Ive seen scores of Long-eared Owls in the past, but I havent seen one this year, reason enough to go seek out this trim, spooky owl and admire it afresh.

Practised on a local level, as in our home county, the year list keeps us on top of local bird happenings. The game becomes more intense when we shift from just keeping a year list to actually working on one, and the game become crazier as we play it in larger and larger areas. I learned this the hard way as a teenager, when I set out to break the year-list record for all of North America. The year that I turned nineteen, I spent more time travelling than birding, in an exhausting, madcap dash around the continent. Was it, as some suggested, an insane and useless stunt? Sure. But I would not have traded that adventure for anything.

For bird lists, the ultimate arena is the world: no fussing with arbitrary boundaries, just go for the whole planet. When I was a kid, few of us thought seriously about trying to bird the world. The number of bird species globally was considered to be about 8,600, but in the 1970s it was almost impossible to find illustrations or precise localities for most of them. If anyone had asked, we would have said that the style of birding practised in the U.K., northern Europe, Canada, and the United States simply couldnt be applied elsewhere.

By that point, however, a few people already were actively birding the world. One of the most influential was the late G. Stuart Keith. Stuart was an intrepid British ornithologist and birder who had moved to the United States and had become the first president of the American Birding Association. I was lucky enough to go birding with Stuart when I was still a teenager. I was tremendously impressed by him, and even more impressed a few months later when he published a landmark article entitled Birding Planet Earth: A World Overview. For many young birders, that article changed everything. Stuart wrote about adventures around the globe, and made it clear that birding the planet was not only feasible but irresistible. He made it clear that anyone could travel and find life birds by the thousands. Indeed, Stuart himself had just become the first to hit half, listing 4,300 of the then known 8,600 bird species in the world.

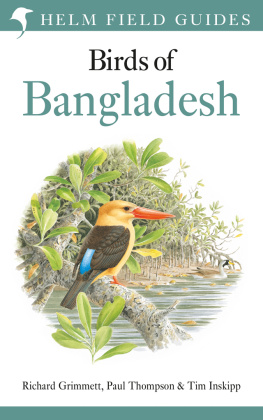

Looking back, its stunning to see how birding has changed. With better understanding of classification, bird species worldwide are now considered to number about 10,000. Almost all are now illustrated in field guides. Travelling birders, scouring the globe and sharing tips, have turned up reliable sites for most; rather than somewhere in the Andes or somewhere in the Outback, they are known from specific stakeouts where you can find them if you work hard enough. In the 1970s, Stuart Keith asked whether it was even possible for a life list to reach 7,000; today dozens of birders have surpassed that mark, and a few have reached 8,000.

But what would happen if the new reality of world birding were combined with pursuit of a year list? For the answer to that, again we turn to intrepid British birders. Alan Davies and Ruth Miller had already decided to quit their jobs and spend 2008 birding around the globe, but their focus changed after a fateful conversation with Iain Campbell, one of the mad geniuses behind the tour company Tropical Birding. Iain is infamous for big ideas, and his response to Alan and Ruths travel plan was typical: while youre at it, why dont you try to break the world record?

Sensible people would have rejected the idea. Alan and Ruth embraced the suggestion and ran with it. The previous record of 3,662 had stood for 19 years, but Alan and Ruth blew it away and kept going. From dawn on 1 January through to the end of December, they grabbed 2008 and squeezed it out for every possible drop of fun and excitement, zigzagging around the globe to see a dizzying and glorious galaxy of birds.

They also encountered a terrifying galaxy of obstacles, from unexpected weather and vanishing reservations to comically bad rental cars and absurd levels of logistical disaster. Ordinary people would have given up and gone home. This extraordinary duo laughed at the challenges and kept going, buoyed up by all the fabulous birds they were seeing. They ended with a one-year tally strikingly close to the 4,300 that Stuart Keith had considered a worthy lifetime achievement back in 1974.

This account of their quest is a page-turner, jam-packed with excitement. If youve ever been intrigued by a bird or by the idea of travel, youll be swept up by this book, with its exotic landscapes, astounding birds and amazing people. The most memorable characters in the story are Alan and Ruth themselves, plucky and resourceful, and filled with good humour in the toughest of circumstances. The fact that they were able to survive this intense level of togetherness for a full year proves that they are both wonderful people, and both crazy, in a delightfully compatible way. In