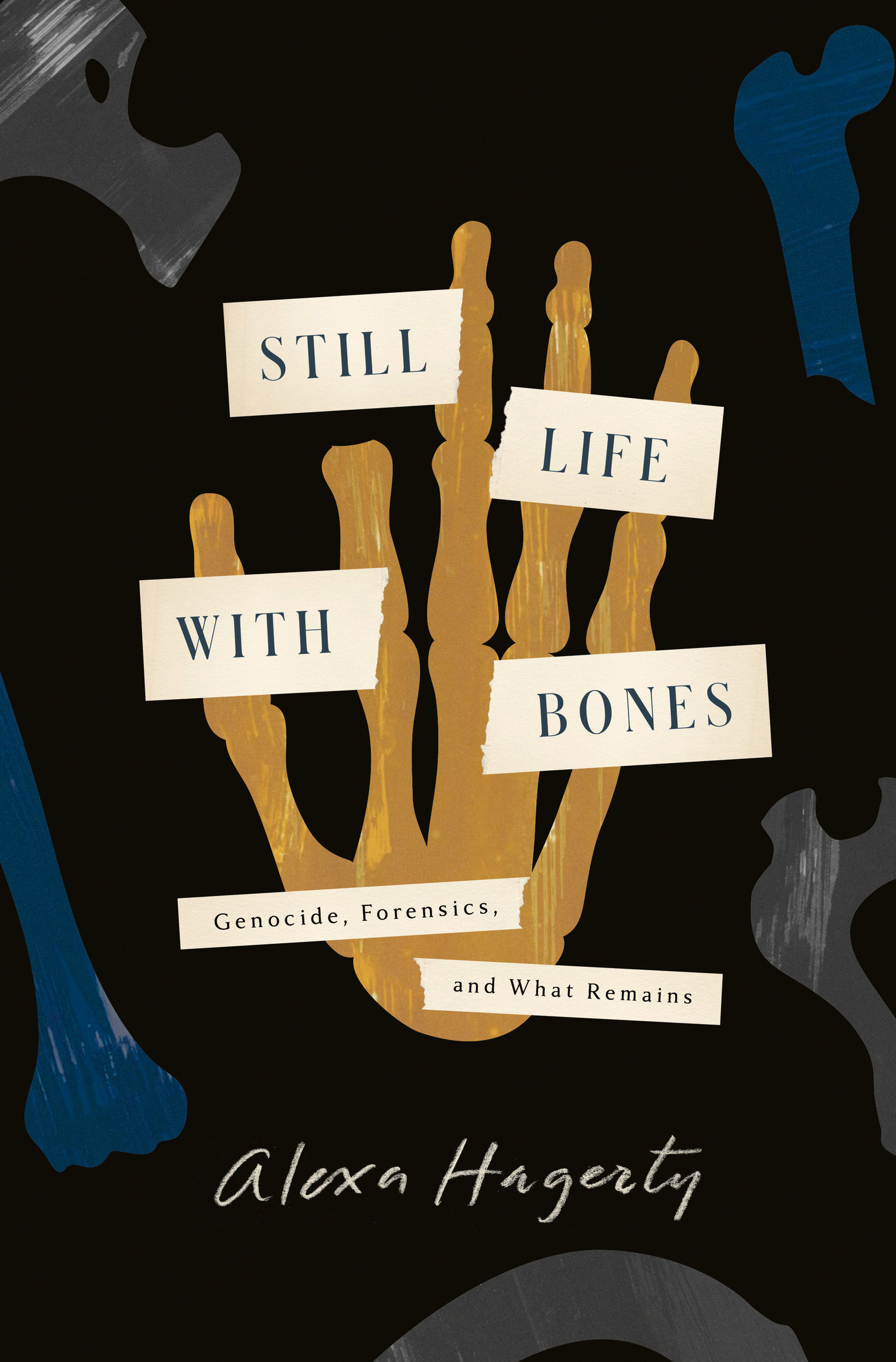

Alexa Hagerty - Still Life with Bones : Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains

Here you can read online Alexa Hagerty - Still Life with Bones : Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2023, publisher: Crown, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Still Life with Bones : Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains

- Author:

- Publisher:Crown

- Genre:

- Year:2023

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Still Life with Bones : Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Still Life with Bones : Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Alexa Hagerty: author's other books

Who wrote Still Life with Bones : Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Still Life with Bones : Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Still Life with Bones : Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 2023 by Alexa Hagerty

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Crown and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Portions of this work were previously published in slightly different form. Portions of the chapter A Lovely Grave for Learning originally appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2018. Portions of the chapter The Ghosts of Argentina appeared in Terrain in 2018. Portions of the chapter Seven Griefs appeared in Ethos in 2022.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hagerty, Alexa, author.

Title: Still life with bones / Alexa Hagerty.

Description: First Edition. | New York: Crown, an imprint of Random House, [2023] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022039668 (print) | LCCN 2022039669 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593443132 (Hardcover: acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780593443149 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH : Forensic anthropologyLatin America.

Classification: LCC GN 69.8 . H 33 2023 (print) | LCC GN 69.8 (ebook) | DDC 599.9dc23/eng/20221109

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022039668

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022039669

Ebook ISBN9780593443149

crownpublishing.com

Book design by Simon M. Sullivan, adapted for ebook

Cover design by Evan Gaffney

ep_prh_6.0_142813758_c0_r0

_142813758_

We have always said that the truth is in the earth.

Rosalina Tuyuc

Following the conventions of anthropology, I have changed the names of family members and team members, as well as the names of the disappeared. On occasion, I have also altered identifying details. Some people requested that I use their real names, and in those cases, I have done so. Politicians and other public figures appear under their real names.

There are 206 bones and 32 teeth in the human body and each has a story to tell.

Dr. Clyde Snow

W hen I first washed bones in the lab in Guatemala, I was aware that I was touching a part of someones body. It was disturbing and uncanny. This has faded.

Months later in Argentina, I wash a skull packed with mud. It is hard to remove; I lean over the sink, intent on the work. Suddenly a maggot slithers across my gloved finger. I scream. My lab mates Emilia and Adriana burst out laughing. Those little gusanos surprise you, says Emilia, who has already pinched the worm between her fingers and tossed it into the trash. Ill clean the rest, she offers. She would probably like to see if there are more larvae in the cranium. I turn down her offer and go back to work, but the skull seems different now. I feel disgust. The maggot signifies rotting fleshand it is horrible. I am acutely conscious that I am holding a dead mans head.

Sitting in front of the sinks with Emilia and Adriana, I scrub recognizable bones from spines, legs, and fingers without thinking much of their humanity. I search their surfaces for interesting features, something worthy of closer examination. This detachment isnt just numbness; it is also the product of an increasing fluency reading the bones. As a certain form of sensitivity dulls, others grow sharper.

I force myself to keep scooping the mud out of the skull cavity. The revulsion slowly ebbs. I think about how this man saw things through these bony orbits. Just as I am seeing him through holes in bone. With this mandible and maxilla, he drank yerba mate tea, kissed someone, spoke kind words, and said things he regretted. Through these bones he heard a friend call his name and smelled earth after rain. I sponge away traces of dirt. I am careful and thorough, feeling penitent for my disgust and also my detachment.

Forensic exhumation is practiced at the crossroads of two ways of thinking about the dead body: as a scientific object to be analyzed for evidence of crimes against humanity, and as a subject, an individual, someone loved and mourned.

In the lab, forensic anthropologists confront collections of bones and fragments that must be puzzled into a meaningful form. Skeletal remains recovered from mass graves are usually incomplete and often intermingled, meaning that the bones of more than one individual are present. Bones may be broken and eroded. Some are likely to be missing, like the tiny ossicles of the middle ear and the smallest of the twenty-six bones of the feet. Forensic anthropologists articulate the skeleton, placing the bones in anatomical order, in the position of someone lying on their back, palms up. Arranging the bones is inevitably an exercise in the partial and incomplete; there are always absences and gaps, elements lost and deteriorated. Anthropologists scrutinize whatever remains, searching for marks of trauma and clues to identity, reading the forensic story the bones tell about a death and a lifetheir testimony of violence.

Before I set foot in a forensic lab, I associated the term articulate with language: the ability to express ideas with clarity or to enunciate words crisply. Bones, like words, can be eloquent. The linguistic root of articulate refers to joining together distinct parts, as bones are united by joints and words strung together into sentences. Both words and bones must be arranged in the right order for their meaning to be clear. Bodies and texts are linked, evident in the Latin word corpus, which means both body and a body of literary or artistic work. This root gives us corpse and military corps, with its suggestion of violence, of many bodies and the dead body.

There is a hidden materiality to textsa word that originally meant weaving, a connection seen in texture. Forests haunt writing: The English word for book is related to beech tree by its Germanic root, and library comes from the Latin for the inner bark of trees. In most Indo-European languages, writing comes from carving and cutting. Language carries the memory of words etched into wood tablets, tree trunks, and bones. Reading bones, as forensic anthropologists do in the lab, is not an analogy so much as a return to the material roots of texts.

The forensic story told in this book explores the matter and meaning of bones: how they are marked by violence and tested in genetic labs. It is also about how bones are always joined to grief, memory, and ritual.

In the late twentieth century, governments in Latin America killed hundreds of thousands of their citizens. Authoritarian leaders directed acts of state terror and genocide against those they labeled as subversives and internal enemies. The catastrophic violence recounted in this book is in the past, but the world is still learning painful lessons about how tyranny leads to atrocity.

The two countries I explore here, Guatemala and Argentina, are different in many ways, but they share a history of disappearancein which people were abducted, tortured, and killed in secret prisons, their bodies discarded in hidden graves. They are also both key sites where forensic human rights practices have been pioneereddeveloped in the long search for desaparecidos, the disappeared. Latin American forensic teams have led the field, sharing their technical expertise and community-centered approaches with the rest of the world.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Still Life with Bones : Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains»

Look at similar books to Still Life with Bones : Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Still Life with Bones : Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.