Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

Our language is constantly changing. Like the Mississippi, it keeps forging new channels and abandoning old ones, picking up debris, depositing unwanted silt, and frequently bursting its banks. In every generation there are people who deplore changes in the language and many who wish to stop its flow. But if our language stopped changing it would mean that American society had ceased to be dynamic, innovative, pulsing with lifethat the great river had frozen up. It would be like Latin, a dead language that does not change because it lives only in books and few living people speak it. America unceasingly reinvents itself, and it must create language to express that reinventionin our social mores, in science and technology, in religion, in politics, in the artsand also to reflect our power and influence in the world.

Curiously and remarkably, John Adams, the future president, foresaw the role of American English even before he knew that the American Revolution would succeed. In 1780, he wrote:

English is destined to be in the next and succeeding centuries more generally the language of the world than Latin was in the last or French in the present age. The reason of this is obvious, because the increasing population in America, and their universal connection and correspondence with all nations, will, aided by the influence of England in the world, whether great or small, force their language into general use.

Whether great or small: it is fascinating that he already imagined such a question in his time.

George Bernard Shaw could joke that England and America are two countries divided by the same language. But H. L. Mencken argued that American and British speech had evolved so differently that by the beginning of the twentieth century Americans had as reasonable a claim as the British to consider English their language.

Voluminously and wittily, and animated by more than a little Anglophobia, Mencken demonstrated that our language began to diverge from the mother tongue almost as soon as the first colonists arrived in North America. He also showed that, for all the British fulminations about American usage, they could not resist adopting Americanisms: Even to belittle, which had provoked an almost hysterical outburst from the European Magazine and London Review when Thomas Jefferson ventured to use it in 1787, was so generally accepted by 1862 that Anthony Trollope admitted it to his chaste vocabulary. Recently it was pointed out that the color robins-egg blue, widely accepted in Britain, is an Americanism, because English robins lay brown eggs.

By his fourth edition, in 1936, Mencken had concluded that the pull of American has become so powerful that it has begun to drag English with it. He even predicted that, with the Englishman yielding so much to American example, what he speaks promises to become, on some not too remote tomorrow, a kind of dialect of American. Has that tomorrow arrived? We wont be impertinent enough actually to ask the English, Do you speak American? The British public would laugh at the notion. Still, British scholars have long conceded that American English is the more influential version of our now global language.

At a news conference in London a few years ago, Prince Charles uttered another of those testy cultural pronunciamentos so endearing to his future subjects. His target was American English, which, he said, tended to invent all sorts of new nouns and verbs and makes words that shouldnt be. He went on: We must act now, to ensure that Englishand that to my way of thinking means English Englishmaintains its position as the world language. Linguists would challenge Prince Charles on two grounds:

First, the concept of words that shouldnt be is alien to the freedom inherent in English. Some people may not like some words, but no one has the authority to forbid their use.

Americans do invent all sorts of nouns and verbs and make verbs out of nounsas do the British. Some new American verbs may be thought ugly, like prioritize; some too close to the cultural edge, like gocommando, from the TV series Friends, meaning to go out without underpants; some too obviously riding the news, like the post-Enron to be401kd; some extreme psychobabble, as in the film What Women Want, when Helen Hunt says, I didnt mean to guilt you; but some just exuberantly creative, as when a flight attendant was overheard saying, Were late leaving the gate because we overboarded the aircraft, so were going to comp the headsets in economy.

It is simply in the nature of English speakers to do this, and of some in every generation to despair. One estimate is that a fifth of all English verbs began life as nouns.

The other response to Prince Charles is that American, not British, English is the engine driving the language globally. Spoken by four times as many people as British, American English reflects Americas superpoweror, as the French put it, hyperpowerstatus (love it or hate it) in virtually every field: in literature, fine arts, popular culture, movies, music, television, science, medicine, space exploration, technology, industrial efficiency and productivity, the power of Wall Street, and American military and political might.

As a result, says the Oxford Guide to World English, American English has a global role at the beginning of the 21st century comparable to that of British English at the start of the 20thbut on a scale larger than any previous language or variety of a language in recorded history. The Oxford English Dictionary now has to maintain a New York office to keep its database and publications current with American usage.

A New York Times story about Americanisms newly adopted by the mother dictionary in Oxford led with this sentence: Hear the one about the fashionista and his arm candy who live in parallel universes, prefer chat rooms and text messaging to snailmail, suffer sticker shock at the cost of pashminas and like chick lit or airport novels?

Still a revolutionary society in our rapid acceptance of new lifestyles, manners, and morals, the United States, albeit with some backsliding, has been a world leader in recent decades in promoting equality for women and blacks; environmental protection; health, fitness, and dieting; and the reduction of smoking. And our society has undergone a transformation to new levels of informality in clothing, eating, and personal relations.

To communicate all of this, American language adapts. Think, for example, of how you guys has now become a generic form of address: it is gender-, age-, and class-neutral, and decidedly informal.

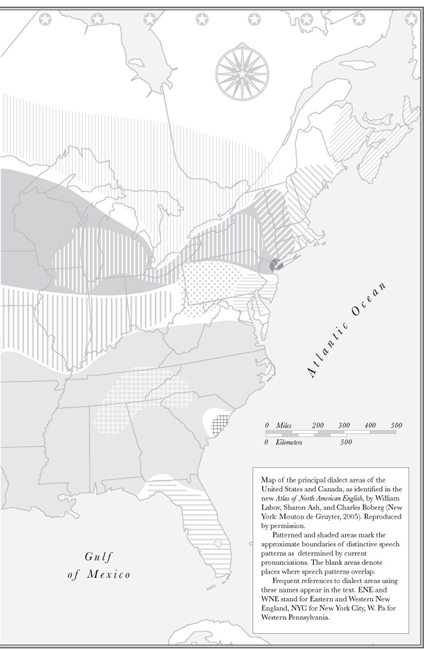

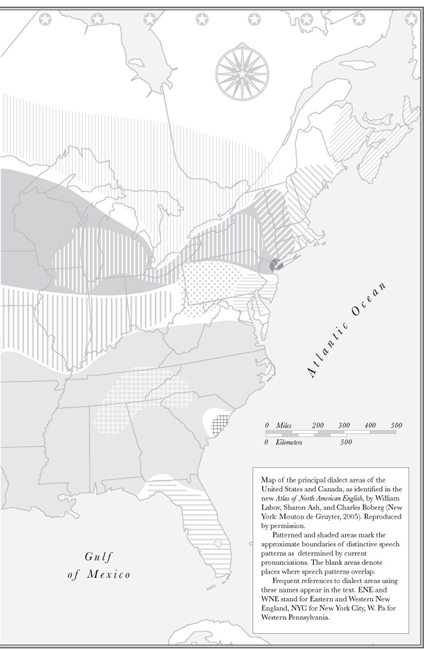

Well, if American English is so vigorous and influential, and millions speak it, why ask, Do you speak American? The answer really supposes another question: what is American English today, when Americans may speak Cajun, Chicano or Spanglish, Surfer Dude or Valley Girl, the urban black language of hip-hop artists, or any of a dozen other regional or ethnic dialects that together constitute American Englishsome of them barely intelligible to one another? Add to the mix the extraordinary variety of what is usually considered grammatically standard American, such as the regional speech differences of broadcasters, or of recent presidents from Massachusetts, Georgia, Arkansas, and Texas. With all that variety, is there even an American English to speak of?

Next page