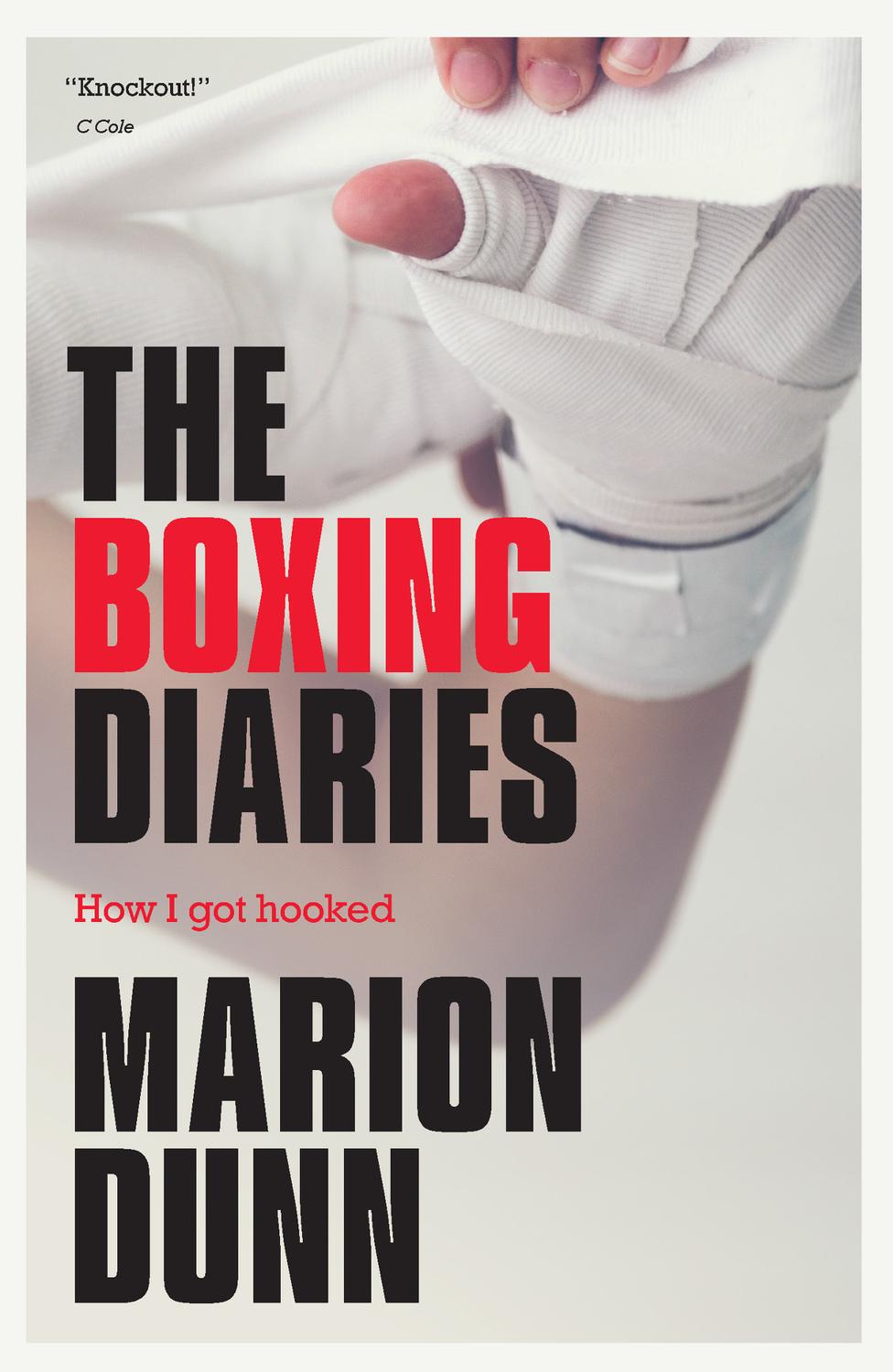

It is 7.45 p.m. on a Monday night in October 2013, and I swing the car round into the car park off the small side road. It is not actually snowing yet, but nearly. Over the previous few months, I have festered, putting on unacceptable amounts of weight. This has led to a search for cheap gyms in my local town. According to various websites, there is a gym here at the youth club just down the road from work which is open to the public three evenings a week. I am not flush with cash so the advertised cost of 2 per session is the decider. Although I am no youth, I push the doorbell and wait.

A largish, friendly man opens the door and introduces himself as Stuart. He leads me into the recreation room, which contains a tatty, blue table tennis table plonked in the middle, plus a few plastic tables and chairs set out for drinking tea and coffee. Next door is a kitchen with a serving hatch. Two podgy kids with thick glasses are pinging and ponging their lives away. I look through two dusty internal windows into the gym itself. I am expecting deep carpets, svelte people in Lycra, coffee and other glistening machines, but instead there is a slightly drab and silent gym. The surroundings are Edwardian no, Victorian, but for the presence of electric light. The walls are lined with bricks, painted in powdery red up to half the wall height, then above a stark, military grey. An ancient football has become lodged in the dusty ironwork that holds up the ceiling. There is a yellowing linoleum floor marked out in white paint as badminton and basketball courts.

Suddenly there is a blast of noise, which sounds much like very garbled speech reverberating. I see the back of a mans head bobbing up and down through the internal windows, then ten children, ranging in age from about eleven to sixteen, leaping and jumping up in time with the shouts. There are four boxing bags hanging from sturdy, black iron stanchions in the opposite wall. The children become locked in their own worlds, pummelling away on the bags for all they are worth. There is a brief lull in proceedings when the shouting stops. Then more shouting, jumping and pummelling.

Stuart tells me that he is the senior youth worker there and introduces me to the cheap delights of the adult boxing club: The adult session follows the youth session. It is free for the first night, 2 per session, and then 10 to join insurance, you see. I have somehow materialised in a boxing gym. Well, give it a go, I think. At the age of fifty, Ive got no shame and have nothing to lose except my pride. As I optimistically part with my 10, I wonder what I am insuring myself against. Possibly the most dangerous aspect is deciding to turn up in the first place. This Christian youth club is subsidised by the charity Children in Need, and I wonder if God would approve of all that pummelling, and if I already am or will be in need. My previous encounters with boxing were nil as a participant, and only limited as a spectator, although I do remember choosing a boxing book out of the school library when aged about seven and being quite fascinated by it. Perhaps it was the sheer quirkiness and the slightly transgressive element that appealed to me, as in the late 1960s this was not a sport promoted for girls.

Brendan arrives; I later find out that he lays carpets on oil rigs for a living. He looks like he knows what he is doing, and I watch intently as he puts on the boxing wraps, long strips of fabric that he winds around his hands.

Eventually the pale, sweaty kids heave out of the gym and lurch for their various electronic devices, then parents. They all look exhausted. That will be me in a minute, only much worse. Rather nervously I enter the gym. It smells of toil and sweat and chalk. I explain to the boxing coach, Gerard, that I would like to get fitter.

How fit dyer think yer are, love? he says, in a thick Scouse accent and with a wry smile.

I say rather lamely that I have a chequered history of various outdoor pursuits, including potholing, and that I am not as unfit as I might first appear.

If yer can stick the first month, yousell be well on the way, love. Ill ask yer again in six weeks, he says without a flicker of malice.

I suspect that he is one who has seen it all before, legions of youths and adults and their aspirations, hopes and dreams come and go. Franois arrives. He is a dapper French chef, with a sharp haircut, who kindly gives me a bottle of water which he says I will need. I later discover that his name is not Franois at all, but Gaspard. Gerard calls him Franois and no one seems to mind.

No one can pronounce my actual name, so I immediately and permanently become my boxing alter ego, Marianne. Peter arrives. He is late and is sworn at by Gerard as soon as he enters the gym. He is black and has a public school accent. He is known as the Politest Man in the World, and he is. Nobody knows much about Peter except that he is extremely well mannered, owns a nice Border collie and washes up in a pub.

At Gerards barked-out command, we all start to skip. It is exhausting. I have not done this since the playground over forty years ago, and none of the right muscles or even bones are in place. My feet ache, my shins ache, my knees ache, in fact all of me aches, but I keep going, the rope swishing and slapping onto the floor, feeling heavier by the second. By chance, I have picked out an orange plastic skipping rope of exactly the right weight and length. It will become both friend and foe over the coming months.

I am severely out of breath, but I carry on as Gerard swears his own kind of encouragement. You lazy fkers, he shouts. Youve all got lazyitis! He turns to me apologetically, Not you love. Sorry for the language. But there is no need for apology. Next we run around the gym, alternately dropping left and right hands to the floor, lurching from one direction to the other as Gerard shouts: Change! Change! Change!

Against all modern Health and Safety legislation, Gerards Staffordshire bull terrier DJ runs around the gym with us. I like DJ, but I wonder about what happens if he gets overexcited and starts nipping at our heels. Next we do some stretching, arms whirling and legs thrown to each side. The dog barks and jumps to waist height as if on springs. All my joints loosen. I am dripping with sweat and very glad for that small bottle of water that Gaspard has provided. DJ stops orbiting the room and finally calms down. This is a relief to us all.

I go into the boxing store to get my first ever pair of worn, red boxing gloves. The store is a small, dark room next to the gym. It has its own smell of ancient leather, dried sweat and something unidentifiable. There is an old weighing machine painted in telephone-box red in the corner of the room, similar to the Speak Your Weight machines that used to be popular in penny arcades. Rows and rows of boxing gloves and headgear are ranged in size order on wooden shelves. A decaying wooden desk in the corner has drawers which are stuffed with boxing wraps. Like multicoloured carnival ribbons, they spill out onto the floor. Spare boxing bags are stacked like coffins near to the door and twenty skipping ropes of differing weights and lengths dangle from hooks on the wall.

Brendan shows me how to put on the boxing wraps. Apparently, the wraps are not really designed to provide cushioning for the hands. Instead, they pull together all the small bones of the hands, so that any impact does not allow them to splay outwards. This reduces the chance of a broken hand now and arthritis later. It is the gloves that provide the cushioning. The wraps also absorb sweat from the hands, and prevent the passing on of any blood-borne infections. I have read that the famous boxer Muhammad Ali had to have cortisone injections into each knuckle prior to a boxing match. Ouch. I learn that if you bash your hands too much, bad things follow.