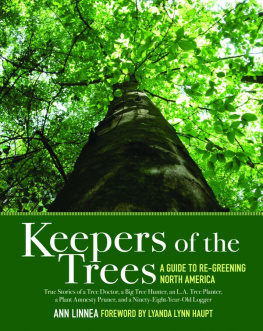

Keepers of the

Trees

Keepers of the

Trees

A GUIDE TO RE-GREENING NORTH AMERICA

ANN LINNEA

Skyhorse Publishing

Copyright 2010 by Ann Linnea

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 555 Eighth Avenue, Suite 903, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 555 Eighth Avenue, Suite 903, New York, NY 10018 or

www.skyhorsepublishing.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Linnea, Ann, 1949

Keepers of the trees : a guide to re-greening North America / Ann Linnea.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-61608-007-5

1. Forests and forestry--Citizen participation. I. Title.

SD387.C47L56 2010

333.75160922--dc22

2009052030

Printed in China

For my dear adult children, Brian and Sally

For my beautiful first grandchild, Jaden Joseph Villarreal

And for all of the children of the world

May you breathe deep and climb high.

Contents

Index

Foreword

W HEN I WAS A YOUNG graduate student with activist tendencies and a Stumps Suck bumper sticker on my ancient Subaru, I kept an old travel trailer on the Olympic Peninsula. Most of my masters thesis on radical environmental philosophy was written there, though Id take days-long breaks, hiking deep into old growth forests of Douglas fir, Sitka spruce, and western red cedar. This was a solitary period for me, and my time among the trees was a sustaining gracethese trees were animate presences in my life, and I came to know many of them as individuals.

One day I returned to the trailer after a long backpack up the Hoh Valley, still excited about the black bear Id seen up so very close. There was a large man in suspenders whod pulled his tiny ramshackle trailer up next to mine. I see youre tryin to put me out of business, he said, pointing at my bumper sticker, and laughing. I raised my brows questioningly. Im a logger, he told me, naming the large company he worked for. Oh, was all I could muster off the top of my head. We talked awhile, just chit-chat. But finally he paused. You know, he looked at me straight and waved his arm toward Hurricane Ridgethe high stretch of Olympic peaks that rose behind the harbor where we campedI love these trees as much as you do.

In another hour he knocked at my trailer door, as promised, and handed me a yellow plastic plate brimming with the oysters hed foraged that afternoon, deep fried into golden, mouthwatering perfection. Wow, thanks, I managed to say. Ill return your plate later.

Oh, dont knock, he said, Im going to bedhave to get up at 4 a.m. for work.

Those were the most delicious oysters Ive ever hadbefore or since. They were also the most generously offered, and they turned my idealistic young mind upside down. I didnt stop joining protests against logging and the woeful state of national forest management, but I finally understood, maybe for the first time, what this work was really about. It was not about right and wrong. It was about love. Deep, wild, lifesustaining love, more complicated than Id ever imagined.

It is easy to love trees. To feel graced by their presence, enriched by their beauty, playful in their limbs. We need treesa self-evident lesson if you pause to ponder it for even a momentand Ann Linneas wonderful Keepers of the Trees will underscore that lesson vividly. But what this book really brings home is the more nuanced lessonthat trees need us. To see them, to plant them, to know them, to save them. This saving comes from unexpected places, many of which I hadnt even considered before reading this book. Not just the eco-activists, bless them, but also the pruners, the wood-turners, the storytellers, and yes, the loggers.

The people in Keepers of the Trees are themselves like trees in a forestcoherent, complex, connected, yet individually beautiful. In telling the stories of these varied, amazing people, Ann Linnea gently prods us to consider our own role as tree keepers, to find, in the uniqueness of our individual lives, ways to turn the generous gifts that trees daily bestow upon us back upon these quiet givers.

Lyanda Lynn Haupt

Author of Crow Planet: Essential Wisdom from the Urban Wilderness

Pilgrim on the Great Bird Continent

Rare Encounters with Ordinary Birds

Introduction

U P HERE, AT ELEVEN THOUSAND feet, the white, dusty, rocky dolomite soil lies loose on the mountain slopes, swirls around my hiking boots, and kicks up easily in the nearly constant wind. In the mountains, temperature is determined by altitude. Its over 100F in the basin lands far below but barely 70F on the trail this July day. Snow and frost can occur in all twelve months of the year in this harsh, exposed place, and the growing season can be as short as forty-five days. Ballooning cumulus clouds indicate that afternoon thunderstorms are already beginning to build around me, so I stay focused on my exploration, knowing I need to be back to my vehicle before lightening begins flashing. Up here, I am a lone moving target for the fire of heaven.

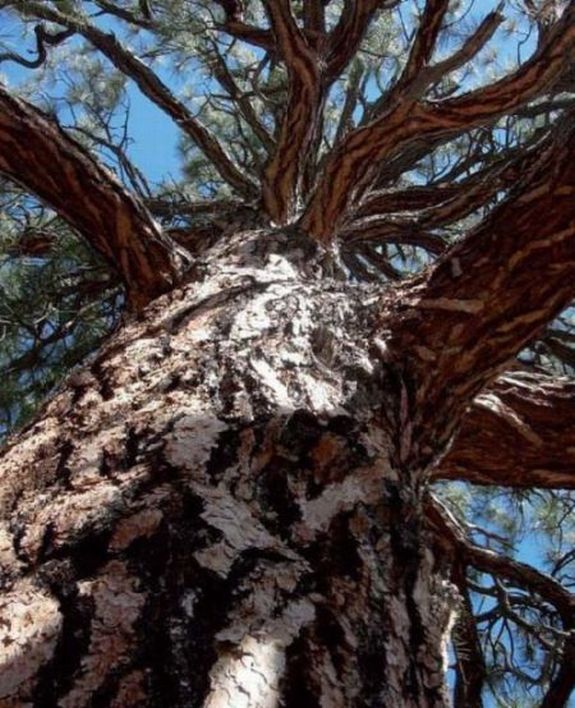

I am dressed in long sleeves and pants, sunglasses and hat. My camera and binoculars bounce on my chest, and my day pack carries the Ten Essentials and an extra bottle of water. I am on a pilgrimage to visit the oldest single living organisms on the planet. They have survived only because they hide out here in this place where few other species can live. They are so rare that only a few groupings of them have ever been discoveredall in remote high mountain slopes like the White Mountains between California and Nevada and in Great Basin National Park on the border between Nevada and Utah. A few specimens that have adapted to lower elevation are hiding in southern Utah in the national parks there. The species I seek is a tree.

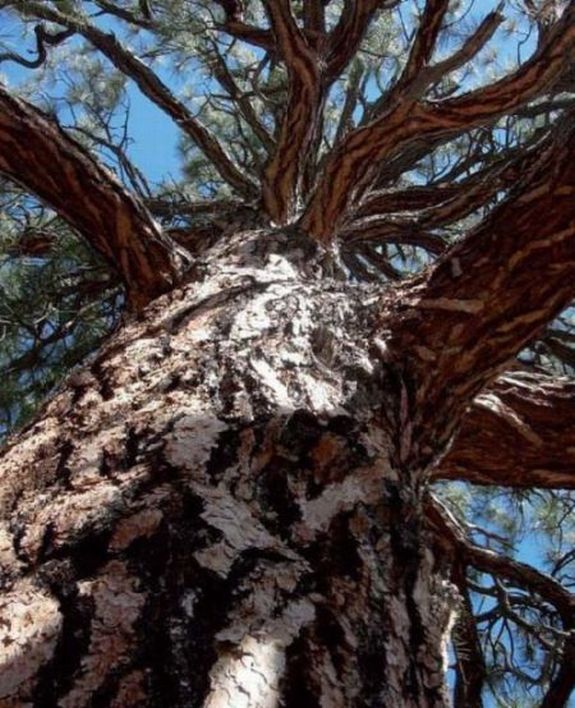

Mountaintop Meeting

Pinus longaeva, the oldest of the three known species of bristlecone pine, are unique, charismatic trees. They live right at or just below the tree line in these few remote mountain sites. Some of the elders stand twenty to thirty feet high, and others grow horizontally along the ground like shrubs trying to stay out of the wind. Bristlecone pines look more like exotic sculptures than trees.

Gnarled, twisted, and able to survive with only a few inches of living bark tissue carrying nutrients between roots and limbs, bristlecones have rock-hard wood that makes them nearly impervious to insect infestation or decay. A two- or three-foot-tall bristlecone sapling that brushes my pant leg may be nearly a century old. We determine the age of trees by counting the annual growth rings they lay down in their trunks. In a dry, harsh year, a growth ring is very thinsometimes less than a millimeter wide. In a lush, warm year, growth rings in some species of trees can be several centimeters wide. There is no such thing as a lush, warm year for bristlecone pines though. I stop to catch my breath. Around me are living trees that are over four thousand years old and gray sentinels of dead trees up to ten thousand years old. I am walking through a natural time machine.

Next page