Contents

Guide

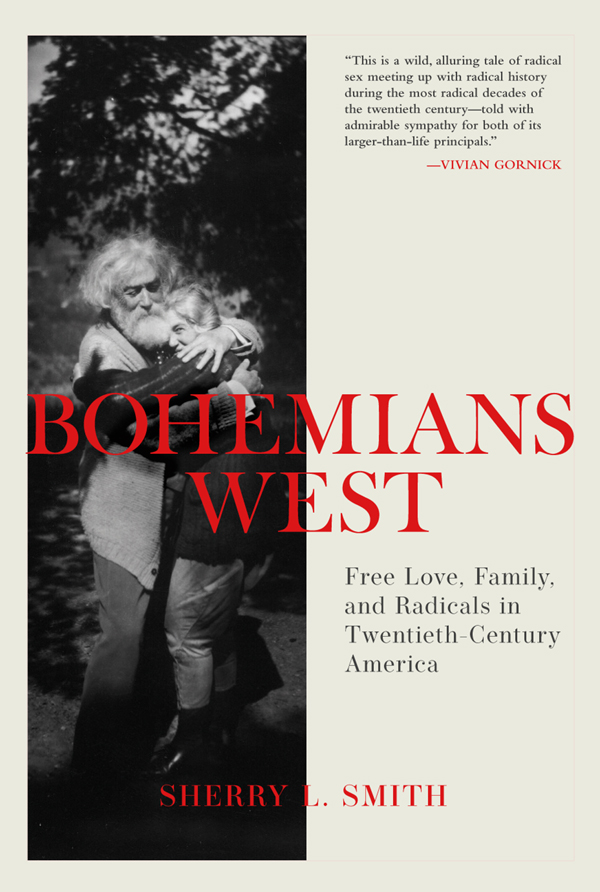

Copyright 2020 by Sherry L. Smith

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Smith, Sherry L. (Sherry Lynn), 1951- author.

Title: Bohemians West : free love, family, and radicals in twentieth-century America / Sherry L. Smith.

Other titles: Free love, family, and radicals in twentieth-century America

Description: Berkeley, California : Heyday, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020015153 (print) | LCCN 2020015154 (ebook) | ISBN 9781597145169 (cloth) | ISBN 9781597145176 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: West (U.S.)--History--1890-1945--Biography. | United States--History--1901-1953--Biography. | Field, Sara Bard, 1882-1974. | Wood, Charles Erskine Scott, 1852-1944. | Man-woman relationships--United States--History--20th century. | Radicalism--United States--History--20th century. | United States--Social conditions--20th century. | United States--Politics and government--1901-1953.

Classification: LCC F595 .S666 2020 (print) | LCC F595 (ebook) | DDC 978/.03--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020015153

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020015154

Cover photo courtesy of the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California.

Cover and Interior Design/Typesetting: Ashley Ingram

Published by Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, California 94709

(510) 549-3564

heydaybooks.com

Printed in East Peoria, Illinois, by Versa Press, Inc.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For

Robert W. Righter

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Sara Bard Field and Charles Erskine Scott Woods love affair began the day Clarence Darrow came to town. Darrow, a nationally renowned attorney for the underdog, visited Portland, Oregon, in October 1910 on business. He also made time for pleasure, bursting into Erskines office and insisting he join him for dinner that night. Darrow wanted Erskine to meet Sara, a reluctant newcomer to Portland. He knew her from the Midwest, where they shared a commitment to progressive politics and the love of a particular woman. Saras sister, Mary Field, was Darrows mistress.

At first, Erskine declined. He planned to take his wife to dinner at the Portland Hotel. But Darrow would not be denied, and when Erskine pressed for more information about this woman, Darrow admitted she was the wife of a Baptist minister. What, Erskine thought, could he, a self-proclaimed atheist, not to mention a philosophical anarchist, possibly have in common with her? Darrow promised, Listen, shes one of us.

Sara, too, resisted Darrows invitation. Erskine was a wealthy lawyer who lived on Portland Hill, an upscale neighborhood above the towns commercial center, where he traveled in the highest social circles. He was much older than Sara, and besides, she had no decent clothes to wear. Darrow persisted, however, so Sara and her husband, the Reverend Albert Ehrgott, joined Darrow and Erskine at the Hofbrau, a bohemian eatery, while Woods brother escorted Mrs. Wood to dinner elsewhere. Thus began a passionate and tumultuous relationship that lasted thirty-four years.

This book tells the story of that relationship and its connection to early twentieth-century American radicalism in the American West. It focuses on people who fought for far-reaching change not only in union picket lines and at suffrage rallies but in homes and bedrooms, in public arenas and in private lives. It charts their determination to transform the nation not from the vantage point of New Yorks Greenwich Village, normally seen as the epicenter of radical/bohemian America, but from the West. And it does so through the lives of Charles Erskine Scott Wood, Sara Bard Field, and their circle of friends and colleaguesa constellation of radicals that spanned the continent. The tale spins out over one hundred years of American history, from Erskines birth in the antebellum 1850s to Saras death in the mid-1970s. Coursing through its pages are tensions between capitalists and labor organizers, militarists and pacifists, suffragists and sexists, politicians and poets. It also explores friction between men and women, parents and children, love and loss, passion and power, freedom and responsibility, selfishness and sacrifice.

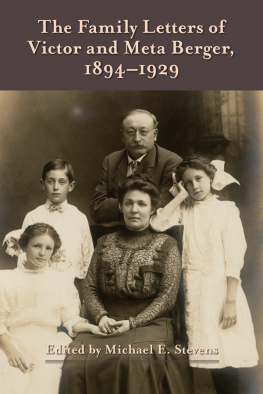

In falling in love and pursuing a life together, Erskine and Sara challenged deeply rooted social conventions as they dove into the radical politics of intimacy. They did not do so recklessly, thoughtlessly, or quietly. In fact, they wrote hundreds of letters explaining themselves and their purpose. They declared marriage obsolete and themselves as pioneers in free love. They advocated a new progressive form of partnership that exalted individual freedom and womens emancipation. Sara and Erskine knew they were ahead of their time and thought their example could be helpful. So, they saved their capacious correspondence, believing a chronicler would someday tell their story and give others the courage to chart their own course for freedom.

In some respects, they proved prophetic about the fate of marriage in the United States. The institution has fallen increasingly out of favor over the last century, and divorce rates have grown steadily, recently plateauing at nearly 50 percent of marriages. Few have thought as deeply or written as extensively as Erskine and Sara about marriages pitfalls or shared the most intimate details of their experiences as free lovers so candidly, with people they would never know. They lived lives of emotional intensity, reflection, and deeply ingrained self-consciousness. But they did not advocate thoughtless or irresponsible promiscuity. Instead, Sara and Erskine attempted to craft a purposeful relationship that joined commitment with freedom. At least, that was the intention. It proved a challenge. The pair differed on issues of timing, levels of commitment, sacrifice, and monogamy. Ultimately, tensions percolated down to which person exercised greater powera calculation that shifted over time.

Family commitments, too, thwarted their ideal love. Sara and Erskine were married with children when they met. Consequently, this is a story as much about those families as about the couple. Both operated in webs of relationship and obligation they could not easily shed. Their love led to heartbreak for spouses, offspring, and other lovers. It tore deep wounds from which some never recovered. For all its light and joy, their affair cast long shadows. And Sara and Erskine were not themselves oblivious to the suffering they unleashed; neither escaped heart-wrenching pain of their own. In choosing to prioritize their desires over those of family members, they wrestled with whether self-realization or responsibility to others, self-expression or self-sacrifice, should prevail. Both believed their lives, for too long, had been defined and constrained by others. They chose one another because they wanted to express their true, authentic selves, even though that meant breaking bonds. They agonized over ending commitments, made in early adult life, to people for whom their love had faded. They wrestled with whether marriage vows and parental responsibility trumped everything else.