2014 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Corsino, Louis, 1948

The neighborhood outfit: organized crime in Chicago Heights / Louis Corsino.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03871-6 (hardback)

ISBN 978-0-252-08029-6 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-09666-2 (ebook)

1. Organized crimeIllinoisChicago HeightsHistory. 2. Italian AmericansIllinoisChicago HeightsHistory. 3. Chicago Heights (Ill.)History.

I. Title.

HV6795.C43C67 2014

364.106097731dc23 2014018821

PREFACE

This book has been some fifteen years in the making. Though in a more comprehensive sense, it has been brewing since I was a young child. Growing up in Chicago Heights, Illinois, I experienced what was in many ways a typical childhood. My father went to work each day; my mother stayed home; my grandparents lived down the block; my house was filled with the working-class status symbols so common during this era (linoleum floors inside the house, aluminum siding on the outside). I earned good grades in the public schools (though my older sisters always earned better grades); I went away to school (my sisters were not encouraged to do so) as a first-generation college student. This seemed like a pretty normal life for a second-generation Italian family in Chicago Heights, Illinois, during the 1950s and 1960s.

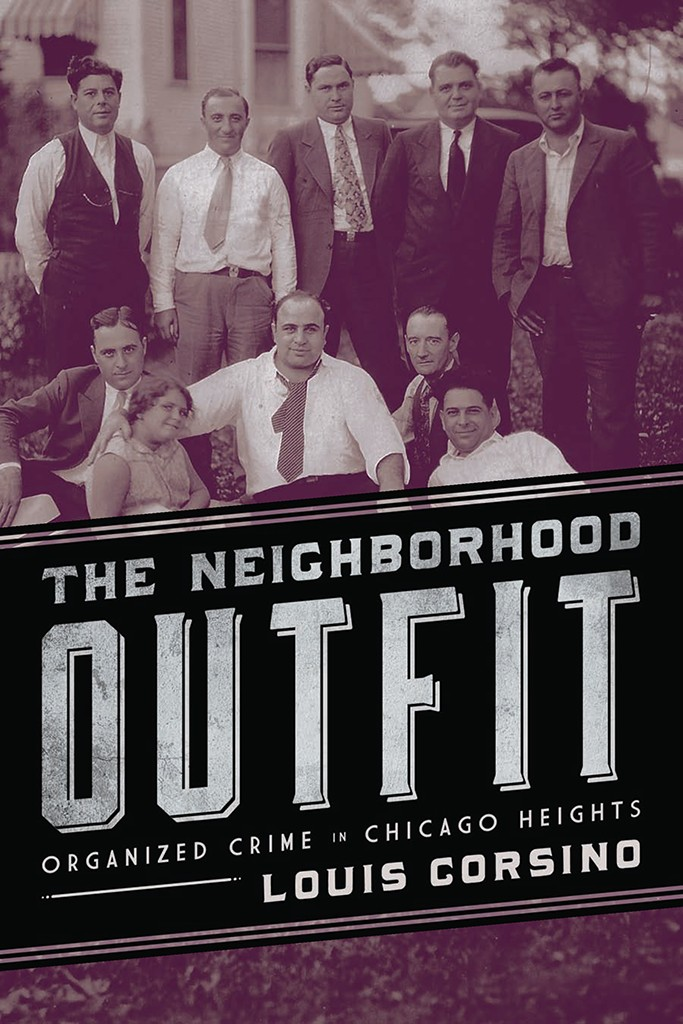

There were signs, however, that there was a world that lay underneath this mundane lifean underworld, so to speak. My father, Andy Corsino, worked for a large part of his life as a route man for a jukebox company in Chicago HeightsCo-Operative Music. This put him in touch with a cast of friends and associates who seemed, in retrospect, a bit unusual. Perhaps, the names should have been a giveawayOne-Armed Jimmy, Black George, Johnny Bum, among others. At the same time, on more than one occasion, my family and my familys circle of friends would have strikingly similar items of dress or household appliances. Years later, Martin Scorsese captured this experience brilliantly in an opening scene of Goodfellas when the mobsters hanging out at the cabstand were wearing the exact, same yellow sweaters that had presumably fallen off of the truck. So many years after my own experiences in Chicago Heights, this scene struck a response cord. And I remember extended family get-togethers at my grandparents house that would periodically become disrupted when Compare John (pronounced JO-wan) (or John Roberts aka Giovanni Roberto) made one of his visits to my grandparents family basement. Roberts commanded great respect on the part of the adults and children. At that time, I had little idea of who Roberts was and why he was treated with this extreme deference. Still, I knew that when we took the family picture (which appears on the back cover), Roberts was to occupy the center position. I knew enough not to ask why.

Over time, I began to put the pieces together. I came to realize that my father (as well as other relatives and family friends) were connected. For example, John Roberts was a leading organized crime head in Chicago Heights and was listed among the top Mafia leaders in the nation by the United States Treasury Department. Other family members and friends were variously at some point in time bootleggers, bagmen, and muscle. I also realized that my father knew a great deal about the organized crime operations and would on occasion be called upon to carry out routine tasks for the boys of Chicago Heights or the Chicago Heights crew of the larger Chicago Outfit, not that my father was a part of the inner circle or took part in any of the violent activities. More so, he was a person who serviced the jukeboxes in the local taverns but who knew about and was friends with the Outfit guys who handled the slot machines in the backroom. Or he would be called up by one of the Outfit bosses to help load the slot machines on a truck in the middle of the night to avoid confiscation by a raid the next morning. Or he would be asked to dispose of incriminating evidence involving any number of organized crime activities perpetrated by the boys.

This more fully formed awareness of my family history came at a cost as I matured intellectually. It raised personal and academic questions as to how a person like my father could mesh himself into this criminal underworld. Characterizations of Outfit members as thugs or goons did not seem to capture the realities of my fathers or most mens participation in organized crime. These were moral classifications, which though justified in a few instances, did not advance an understanding as to why Italians, in particular, dominated organized crime for the greater part of the century. Thus, I wondered whether it be correct to assume that Italians had a greater proportion of thugs and goons relative to other groups in the population and thus were better adapted to organized crime. By the same token, I did not feel comfortable with the explanation that the historical link between organized crime and Italians was simply the result of a few bad apples. Again, such pronouncements seem also to be driven by moral concerns. Certainly, only a small proportion of Italians have participated in organized crime. But a link exists nevertheless and this link ran deeper and was more widespread than many Italians were willing to concede. My family and family friends stood witness to this. How then, I asked, could I make sense of this affinity without resorting to a search for some endemic, enduring stereotypical criminal motive that lay embedded in an Italian personality, culture, or legacy?

With my own familial experiences as a point of entre and with my sociological knowledge in hand, I sought to answer this question with an examination of the boys of Chicago Heights. I drew upon a series of personal interviews, historical records, census manuscripts, and other available resources. The central thesis was to demonstrate how this organized crime operation grew out of the Italian enclave in this community and more specifically how it grew out of the cultural, political, and economic forces at work for the greater part of the last century. In examining these forces, social capital became the key conceptual tool that connected these more encompassing community processes and the ability of Italians to sustain a criminal operation for nearly the entire century. The following chapters detail this argument.

In undertaking such a study, I am keenly aware this analysis falls awkwardly between the popular first-person (in my case second-person) accounts of life in organized crime, on the one hand, and the academic, research-driven explanations on the other. As you read through the chapters, I believe you will find that the academic focus dominates. This was critical because the underlying roots of organized crime transcend the particular historical situation and particular historical actors. Specifically, if we are to understand contemporary organized crime groups, especially those developing out of African American and Latino communities (as they have in recent years in Chicago Heights), academic concepts and insights provide a firm basis for comparison and generalization. At the same time, this academic focus was essential because organized crime proceeds and sustains itself not on the basis of the sensational, headline grabbing activities, but on the more routine social relationships that link organized crime groups to the surrounding community. The first-person, blood-in-the streets narratives often bury these more sociological relevant processes. Indeed,

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.