ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Italian American history and culture is at risk of being lost. I am pleased to acknowledge and thank the following people who understand that we must make sustained and robust efforts to preserve it: Helen, Rosemary, and Steve Andolino; Angelo and Josh Battaglia; Tony Arduino; Hoacio Baggio; Rita Baggio; Gino Bartucci; Cleto Bonanotte; Emil Bracco; Joe Bruno; John Bucci; Dominick Bufalino; Joe Camarda; Fred and Sandy Ciccotelli; Tony Concialdi; Louis Corsino; Antonio DAmbrosio; Pasquale DiMaso; Chris Caliendo; Cathy and Paul Ciminello; Richard Della Croce; Vincenzo DeVito; Maria DiMarco; Dominick Gambino; Giuliano and Maristella Gozzi; Rosetta Grano; Carmelina and Gino Impellizzeri; Anna Clara Ionta; Angelo Liberati; Carlo and Judy Lombardo; Domenico Mancini; Mario Manfredini; Josette and Benedetta Mentesana; Eligio Minini; the Joseph Monastero family; Tony Napoli; Gino and Maria Nuccio; Mina Pacini; Americo, Italo, Phyllis, and Rosemary Petrongelli; Eugene Planera; Dino Porto; Diva Pulcini; Ann Marie and Joe Quercia; Matteo Ribaudo; Tony Romano; Luigi Sciortino; Luciano Silvestri; Peter Silvestri; the John Storino family; Enzo Tribo; Renato Turano; Carlo Vaniglia; and Giovanna Verdecchia. Their specific contributions to this book are indicated by last name in parenthesis at the end of each caption.

All of the 1,000 donated images and the informal interviews conducted in this book project will become a part of the Casa Italia Digital Archive. Please accept my sincere thanks for making this book possible.

Paul Basile and Mary Racila of the Fra Noi have been extremely helpful. I was again impressed by the treasure trove of information that has appeared in the Fra Noi . Each issue that the staff produces is the equivalent of another good book on Chicagos Italians. Readers seeking additional information on the topics touched on in this book should consult the 50 years of back issues of Fra Noi that are on file and microfilm in the Casa Italia Library.

Thanks also to Jeanette Risatti Viehman of the Casa Italia Library, to Anne and Caroline Klos, who tried to get me organized, and to Melissa Basilone, who went beyond the call of duty as acquisitions editor. Thanks to my wife, Carol Cutlip Candeloro, for strategic support in the final stages. This book is dedicated to our grandchildren: Caroline, Daniel, and Matthew Klos and Trevor and Charlie DeButch.

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

WORLD WAR II CHANGED EVERYTHING

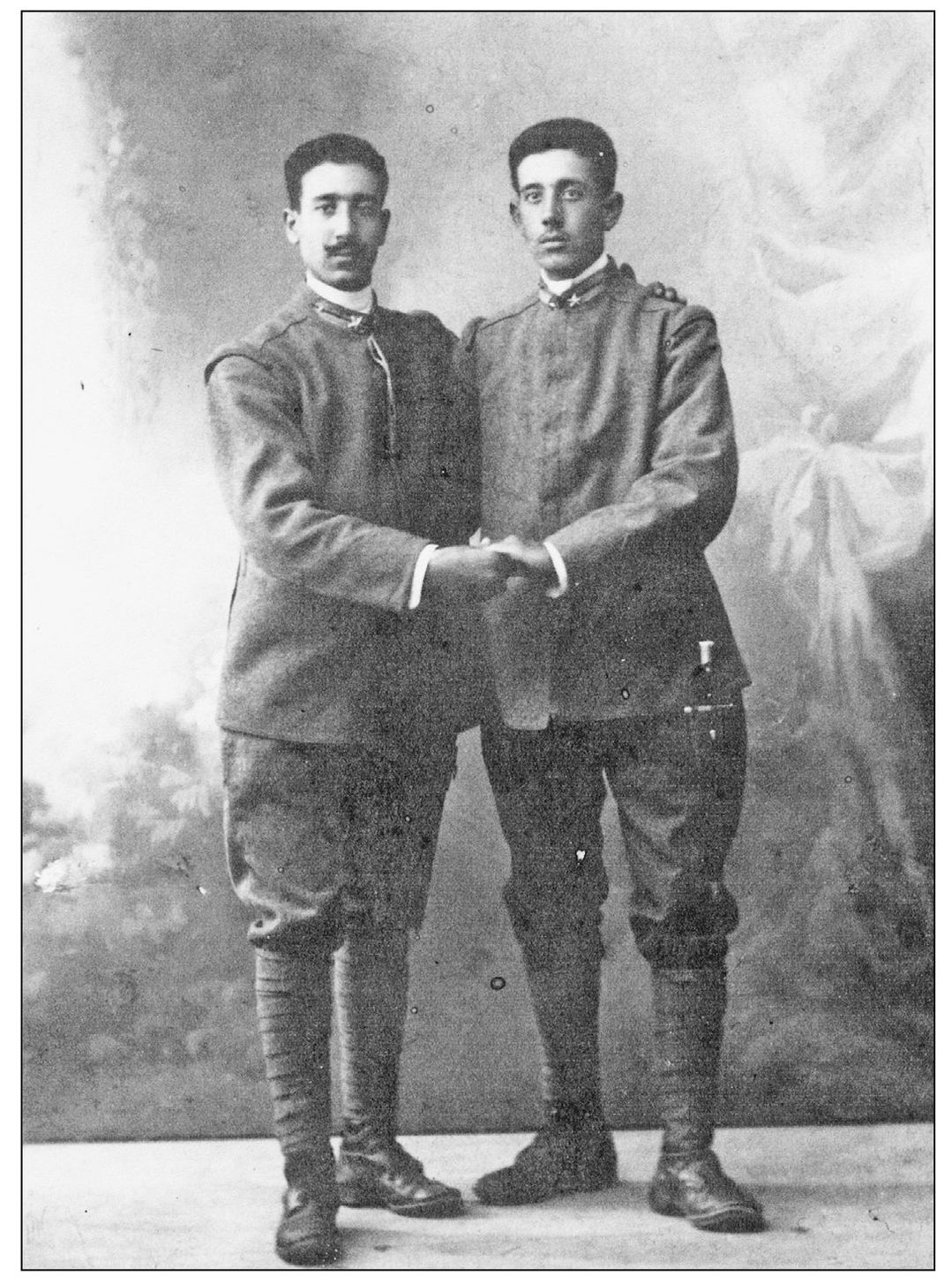

Brothers Carlo and Giuseppe Piombino from Palermo had immigrated to the United States before World War I, then answered the call of their birth nation to return to Italy to defend their homeland in 1916. Their early venture to the United States and Carlos many return trips produced four children born in the United States and two in Italy, the last of whom was Maria Piombino Nuccio. (Nuccio.)

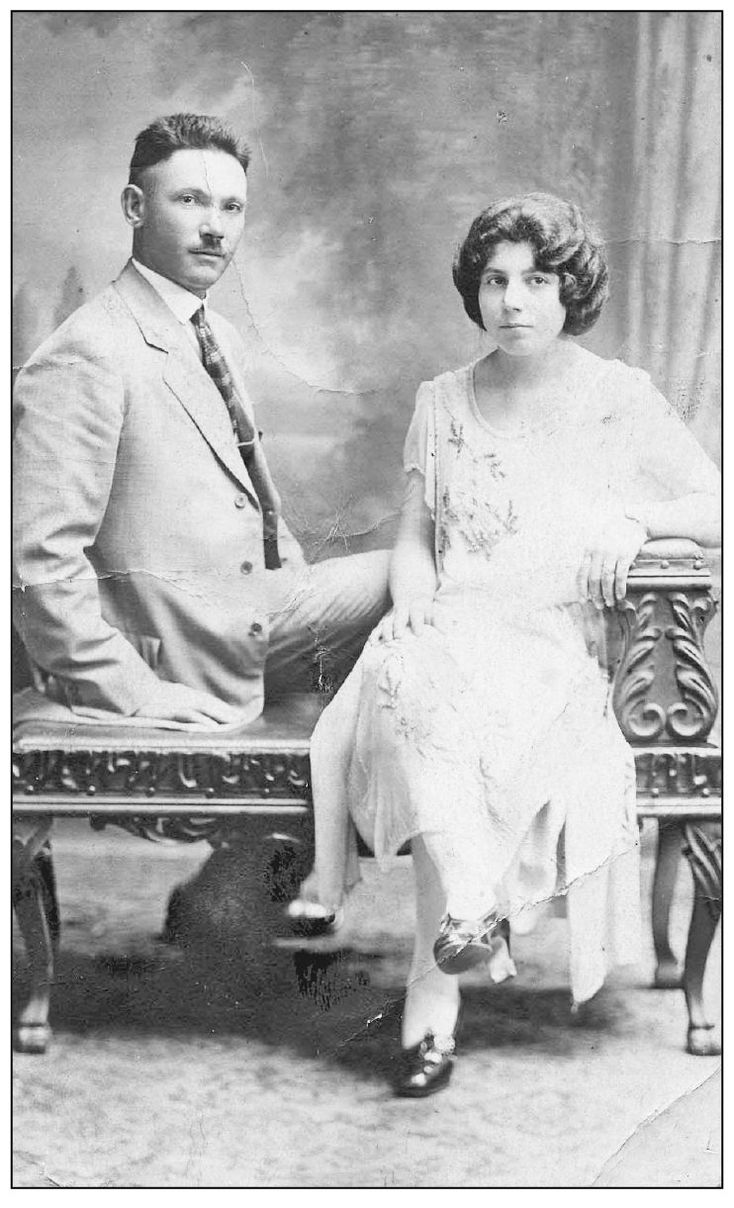

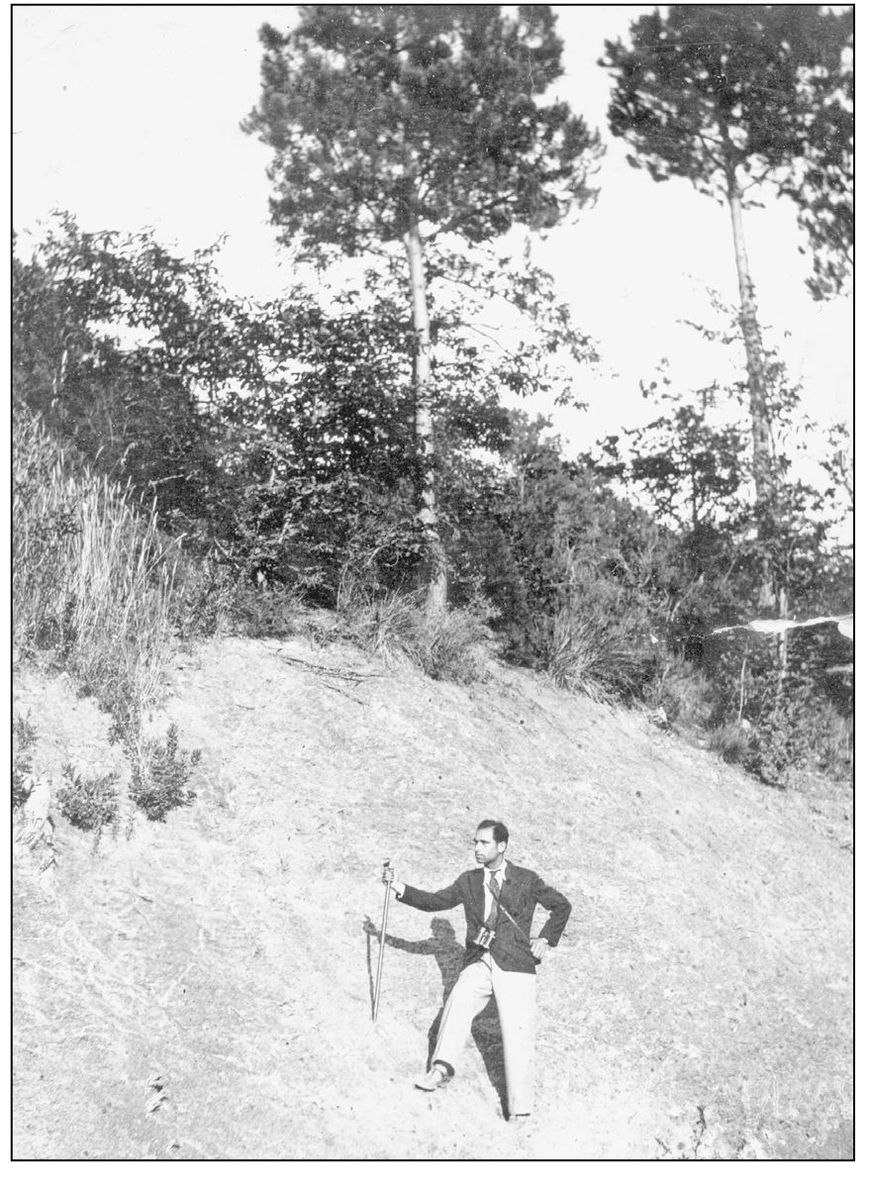

Antonio Petrongelli poses with his cousin Yolanda Giannetti in the mid-1920s in Chicago Heights. Petrongelli gained citizenship and returned to Amaseno in the 1930s, giving his first son, Americo, the right to immigrate to the United States in 1950. (Author.)

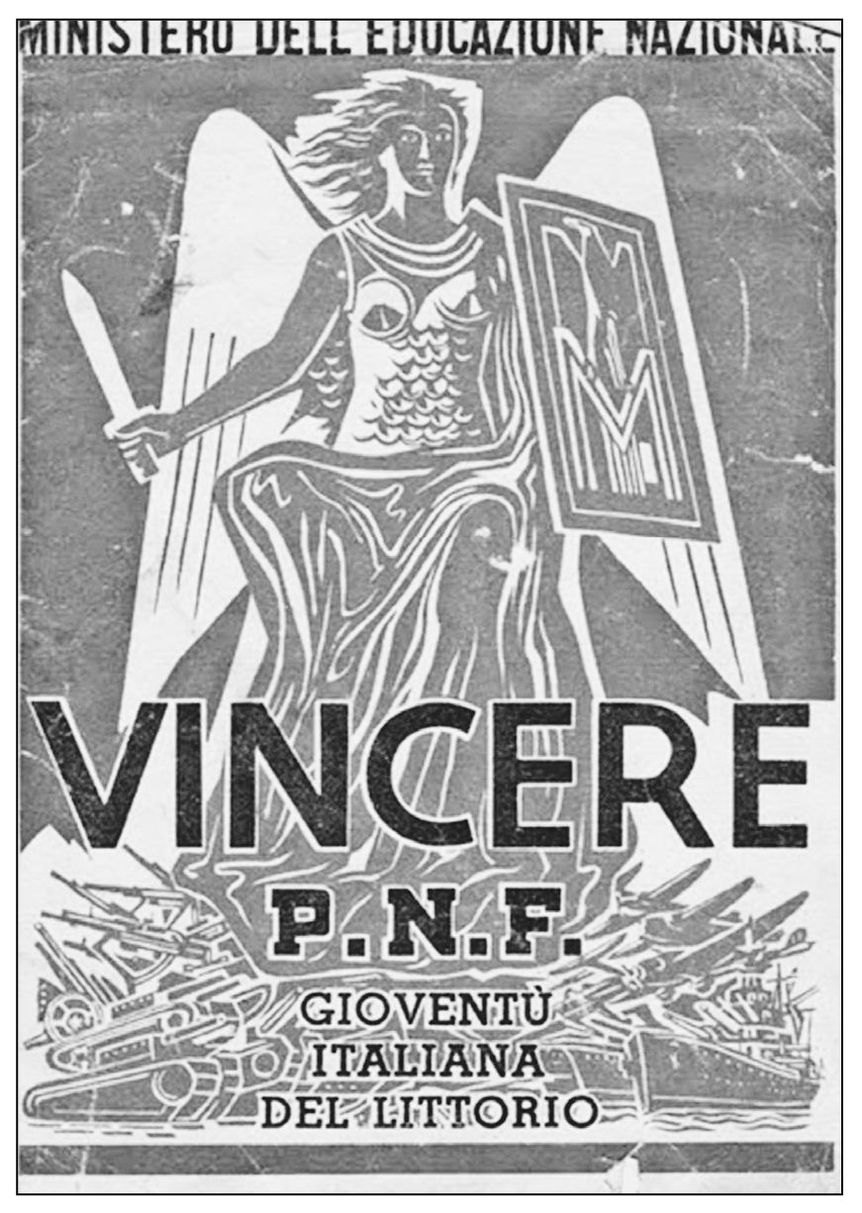

Among the souvenirs of the postwar Italian immigrants to Chicago were report cards. This one from the early 1940s reflects Italys nationalist education policies and fascist propaganda cheering the tanks, ships, and warplanes of the armed forces to a victory that never came. On the other hand, the fascist government vastly expanded public education, and these report cards also symbolize the increased educational qualification of the new immigrants over the preWorld War I group, a sizeable portion of whom were illiterate. (Rubino.)

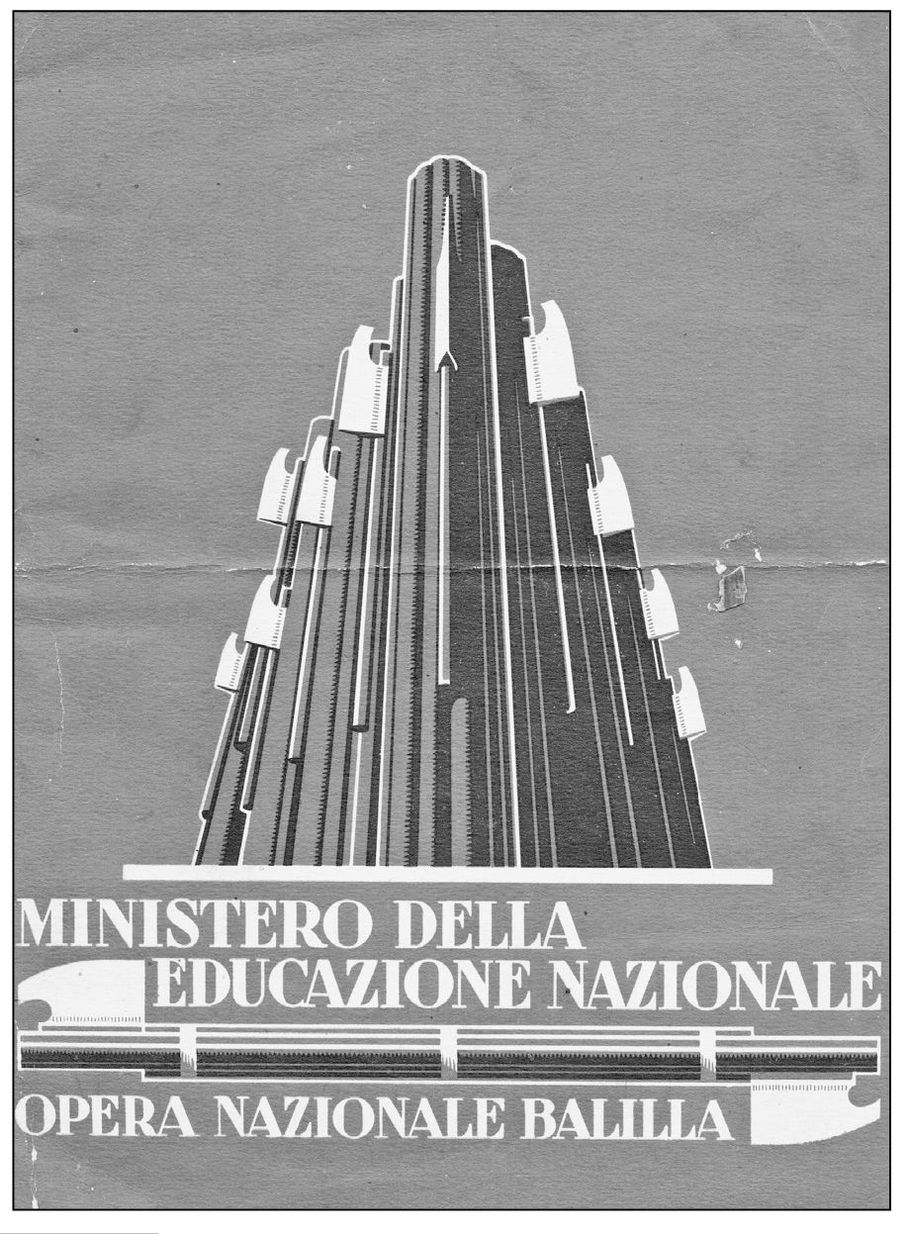

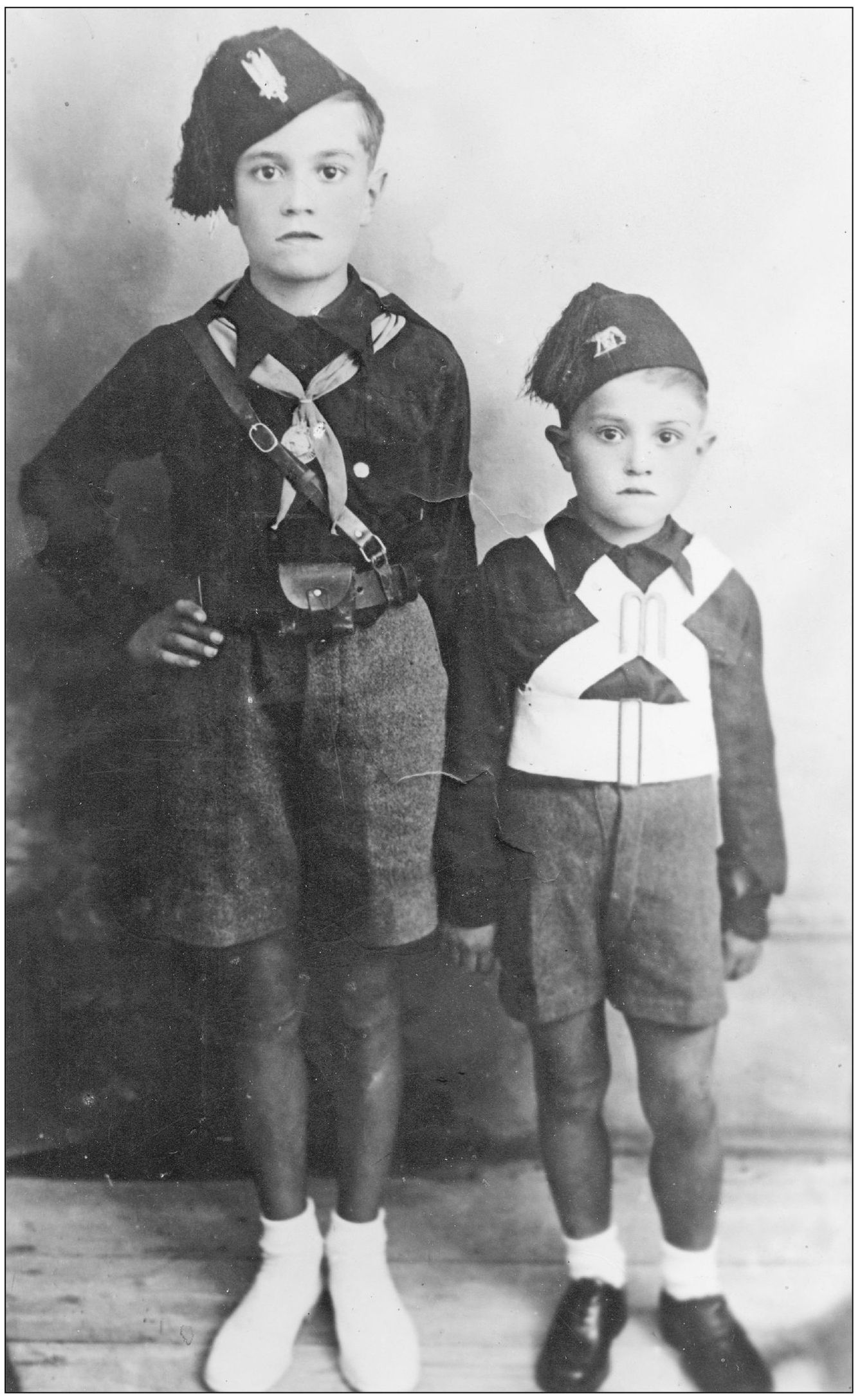

The fascist government put a lot of resources into the development and training of youth, with the object of creating a nation of disciplined and healthy citizens and soldiers. In the years under Mussolini, the Balilla movement, roughly comparable to Boy or Girl Scout programs, functioned during the school week and on Saturdays throughout Italy and even in many of the Italian Catholic parishes in Chicago. (Vaniglia.)

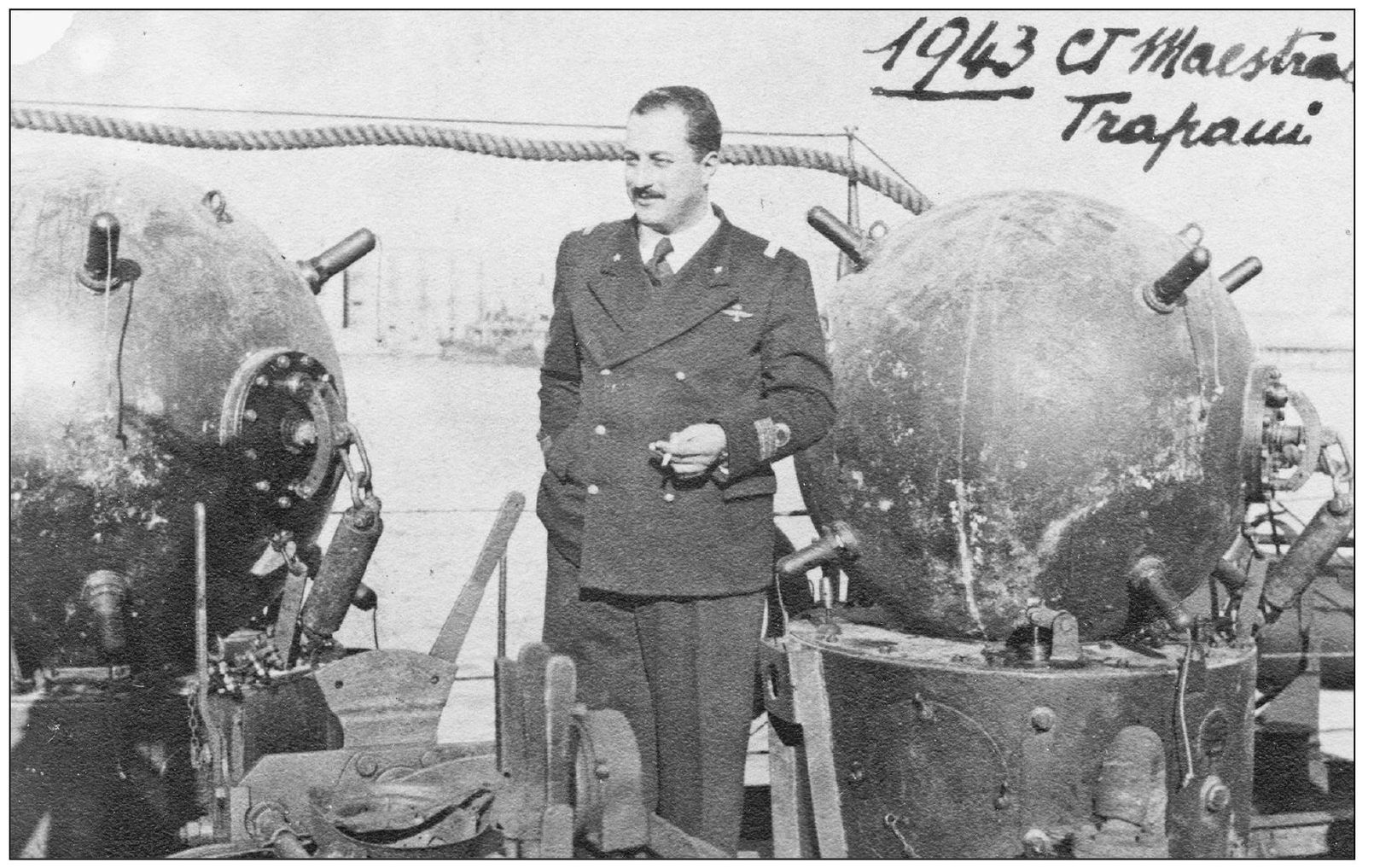

Antonino Ciminello went from Sicily to Africa to work as a civilian colonist. He opened up a barbershop and had a partnership in a stone quarry. He intended to bring all of his family to Africa, but the war came and he was taken prisoner. At the end of the war, he returned to Sicily in a red suit, destitute. Postwar conditions nudged him to accept an invitation in 1954 to join his brother Sam in Chicago. Thus, in a 20-year period, he went from being a colonist in Africa to an immigrant in Chicago. (Nuccio.)

Mario (left) and Manfreddo Ciccotelli were part of the Balilla and the Figli di Lupo, respectively, in Caramanico (Pescara). The large colorized version of this photograph is inscribed Caramanico 5-5-1939 XVII. The Roman numerals represent the literary convention of the time to indicate the age of Mussolinis fascist regime. It never got beyond XXII. These boys came with their father, Eugenio, to Chicago Heights in 1947. (Ciccotelli.)

Vincenzo Tribo was only a year and a half old when his folks dressed him up in this Balilla outfit in Fiume in December 1934. The Balilla gets its name from the nickname of a legendary Genovese boy, Giambattista Perasso, who precipitated the ouster of Austrian occupation troops from Genoa in the 1740s. (Tribo.)

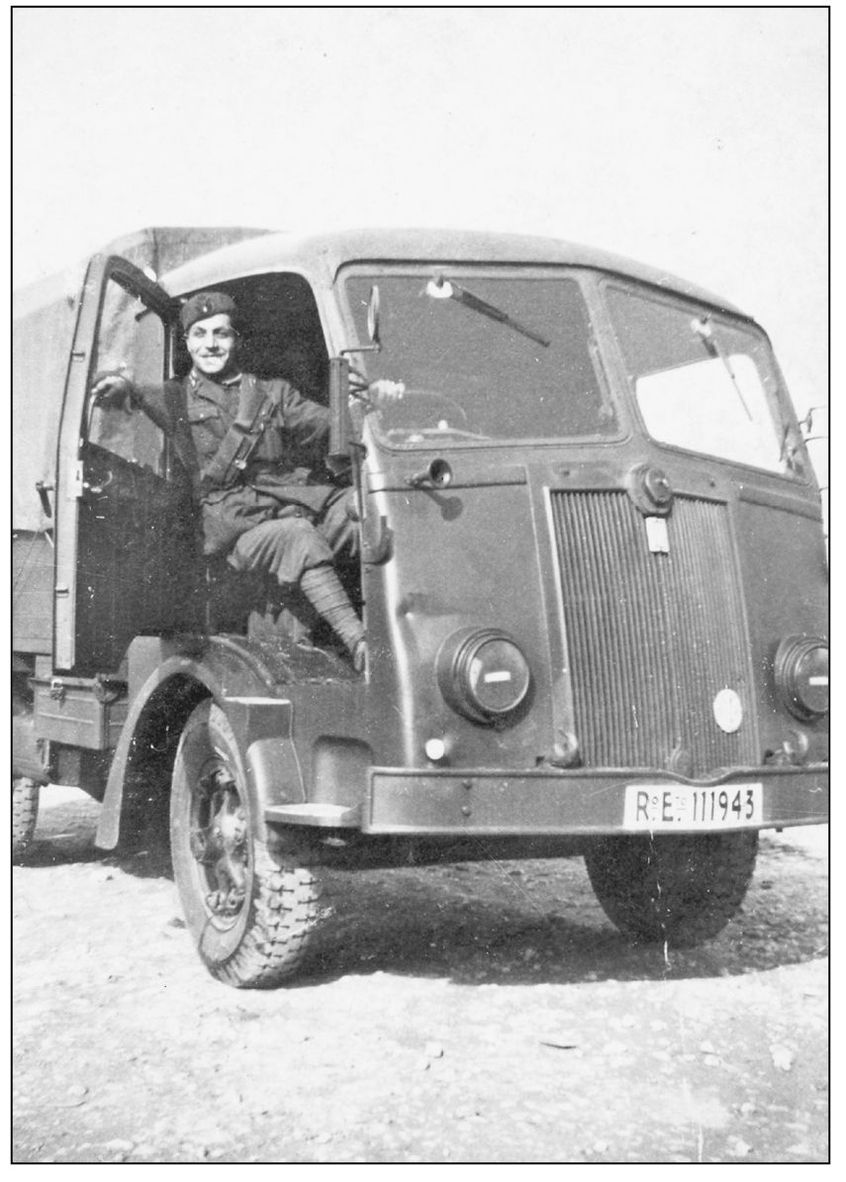

Antonio DAmbrosio spent the early part of World War II as a truck driver in Trieste and ended it being captured and held as a prisoner of war in Africa. He spent more than five years in the Italian Army. (DAmbrosio.)