ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Because a creative work is seldom the result of one individual effort, I would like to extend my gratitude to the collection of folks who offered their time, resources, and expertise. Among those who informed and contributed to Swedish Chicago through their unselfish generosity of knowledge, photographs, and family anecdotes, I would especially like to thank: Clarence and June Anderson, Larry Anderson and wife Patty Rasmussen, Marcia Anderson, Pehr Bolling, Marti Corcoran, Bruce DuMont, Susan Erickson, Andy Freborg, Ray Helgeson, Elizabeth and Ralph Johnson, Rick Kogan, Elsie and John Lindgren, Roy Lundberg, Pearl Magnuson, Madeline Mancini, Vera Nelson, Ann-Britt Nilsson, AnnMari Nilsson, Annette Peterson, Bruce and Sharon Peterson, Evelyn Reese, Miriam Seaholm, Gail and Pat Shaw, Charles R. Smith, and Ingvar Wikstrom.

Several institutions were also of great help during the course of this project and to them I am deeply indebted: Ellen Engseth, director of Archives and Special Collections at North Park University, Chicago; Kerstin Lane, director of the Swedish American Museum Center in Chicago, without whose permission to access the museum, knowledge of the Swedish community, and willingness to inform this project, Swedish Chicago would not have been possible; and, the Chicago Historical Society.

Special thanks to my friend and mentor, Mario Lopez, for his early encouragement; Richard Francis Tracz, for his faith in my scholarly abilities; David and Beth Peterson, Alex Peterson, and Nicole Peterson, for family support; Rahan Ali, for his lifelong friendship; and Joan Bowers for her unselfish love and support throughout the journey of this project. Also, a thousand thanks to my editor, Samantha Gleisten, and the entire staff of Arcadia Publishing who work thanklessly behind the scenes to make these books possible.

Finally, sincere appreciation to you, the reader, for your interest in this text. It is my firm hope that this book will delight and inform your sense of Chicagos Swedish community as you reflectively journey through the century of photographs contained in these pages.

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

THE EARLY YEARS

Leaving a large farming family to immigrate to a metropolis in North America could prove especially distressing to those who came from a land where working the soil was as natural as breathing. But the early Swedes were Vikingsexplorers in search of new lands and welcoming opportunities much like the emigrants who sailed to America centuries later. In Chicago, the Essence of the Promised Land , Ulf Beijbom reports, Of the 1.2 million Swedes who emigrated between 1850 and 1920, approximately every fourth one came from a town. This alters the traditional notion that casts many Swedish emigrants as rural types. Because the intensity of Swedish emigration remained stronger in the towns rather than in the countryside, Beijbom notes, the Swedish desire to occupy cities testifies to the importance of urbanization.

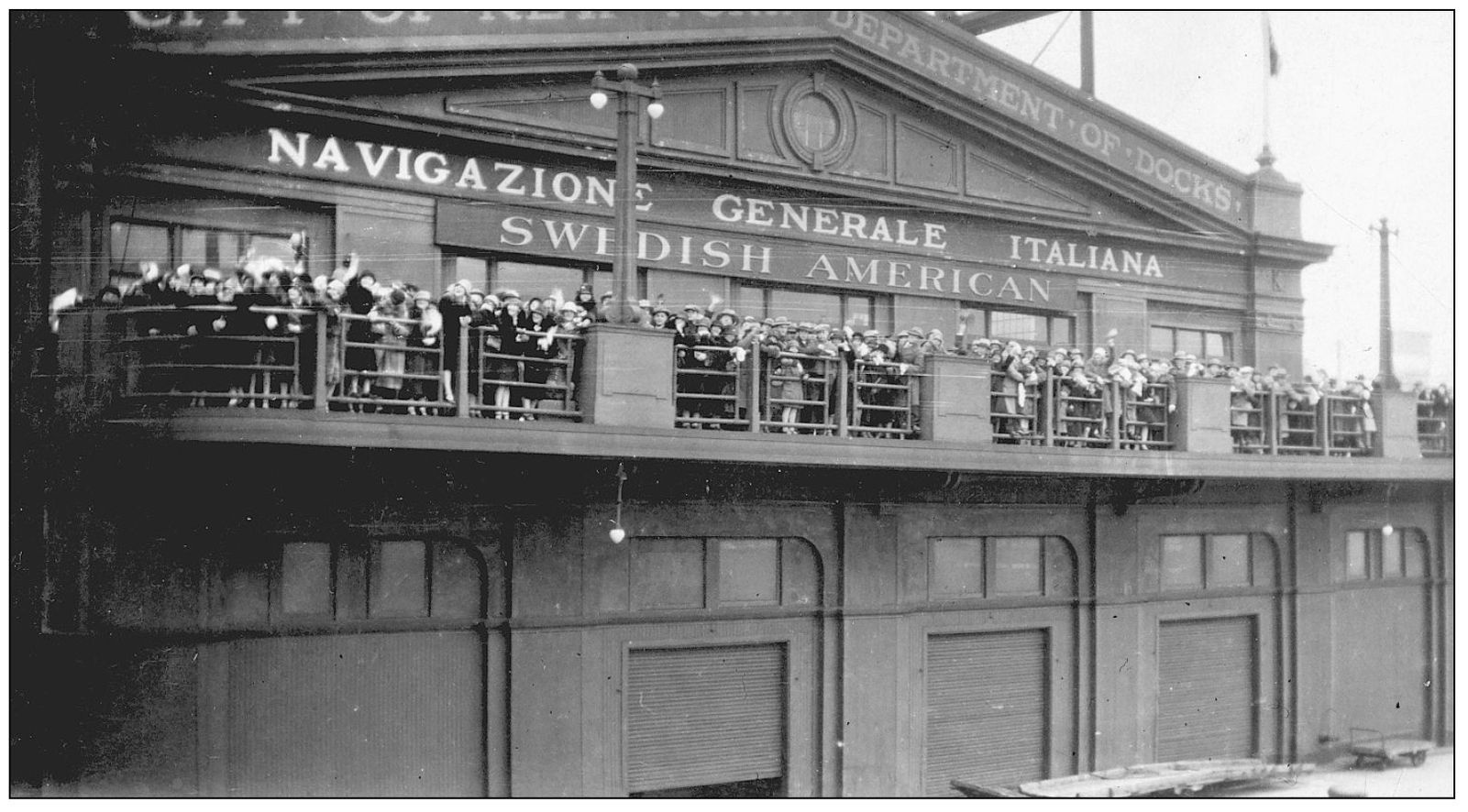

CITY OF NEW YORK, DEPARTMENT OF DOCKS. While those portrayed here are probably exhausted from their long voyage, one can sense the gaiety and anxious excitement on the faces of these Swedish immigrants as they await processing at the port of arrival. (Courtesy of Elsie Lindgren.)

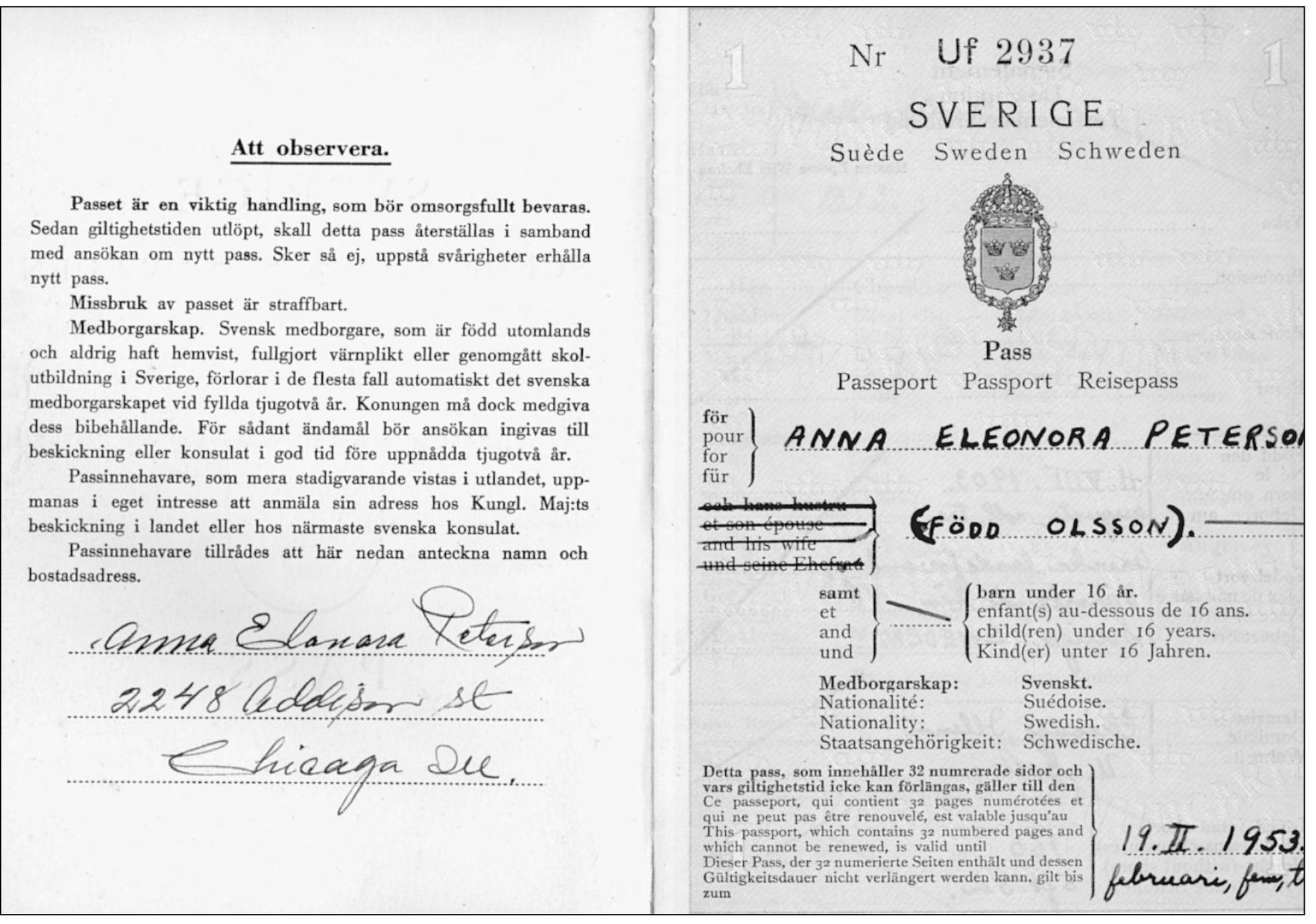

A TYPICAL SWEDISH PASSPORT. Utilized by the authors grandmother for vacation purposes years after her initial arrival to America, this passport reflects an image most common to those who traveled the Swedish American line. (Courtesy of Bruce Peterson.)

CROSSING THE ATLANTIC. Anna Olson (center), the authors grandmother, crosses the Atlantic with two friends as they make their way to the United States. Shortly after arriving in America, she would travel to Chicago, find work in a bakery, and later marry Charles Peterson with whom she had two childrenBruce and Evelyn. (Courtesy of Bruce Peterson.)

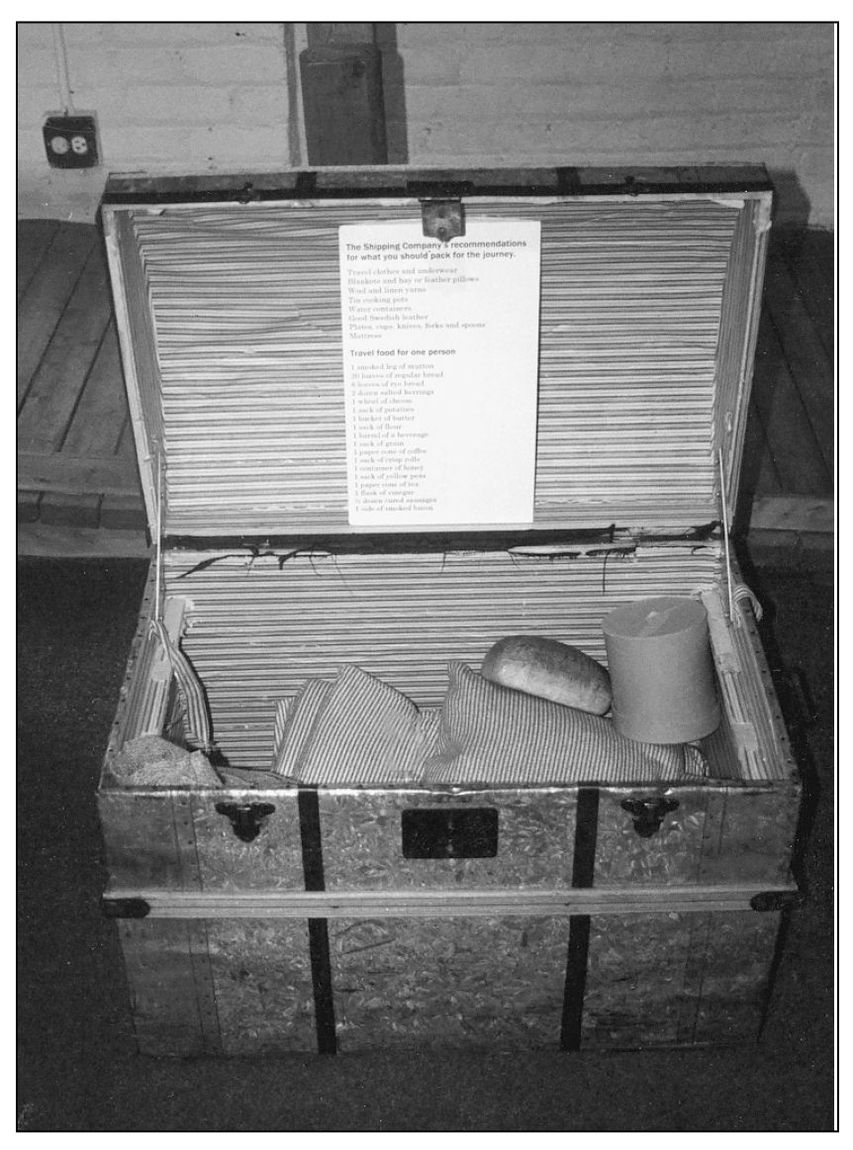

A SWEDISH TRUNK. Travel clothes, blankets, cooking pots, herring, and potatoes were just some of the items typically found in the trunks of Swedish emigrants. Any belongings or necessities to which one desired accessboth during the trip and after arriving in the United Stateshad to fit in this archaic form of luggage. (Photograph by Paul Michael Peterson; courtesy of Swedish American Museum Center.)

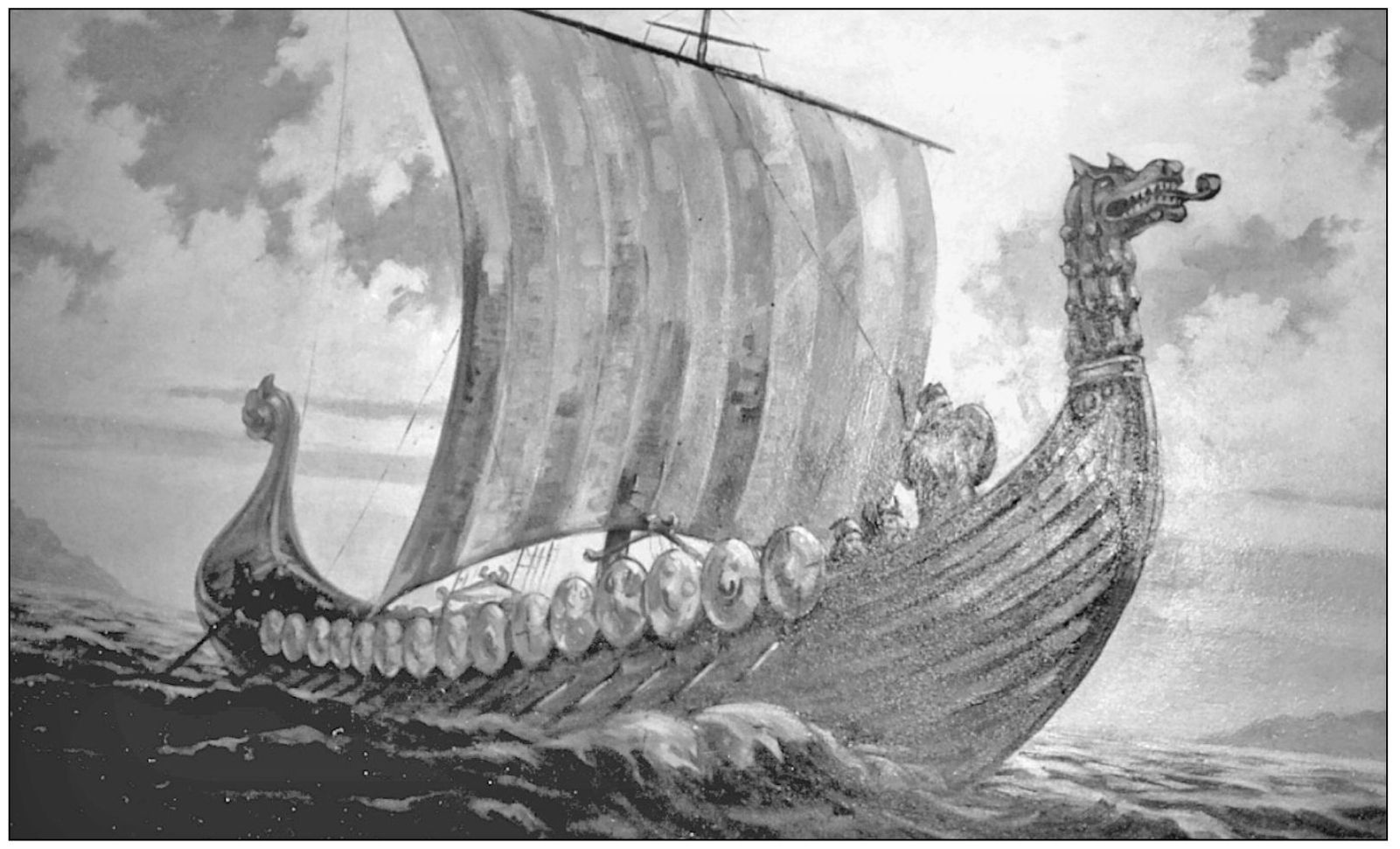

PAINTING OF A VIKING SHIP. Although not a member of the Swedish American line, the early Viking craft illustrated above is an impressive, if less luxurious form of travel. This piece, taken from a three piece mural restored by Edward Olson, was once displayed at the Swedish Club on LaSalle Street before its arrival at the Swedish American Museum Center where it hangs prominently today. (Photograph by Paul Michael Peterson; courtesy of Swedish American Museum Center.)

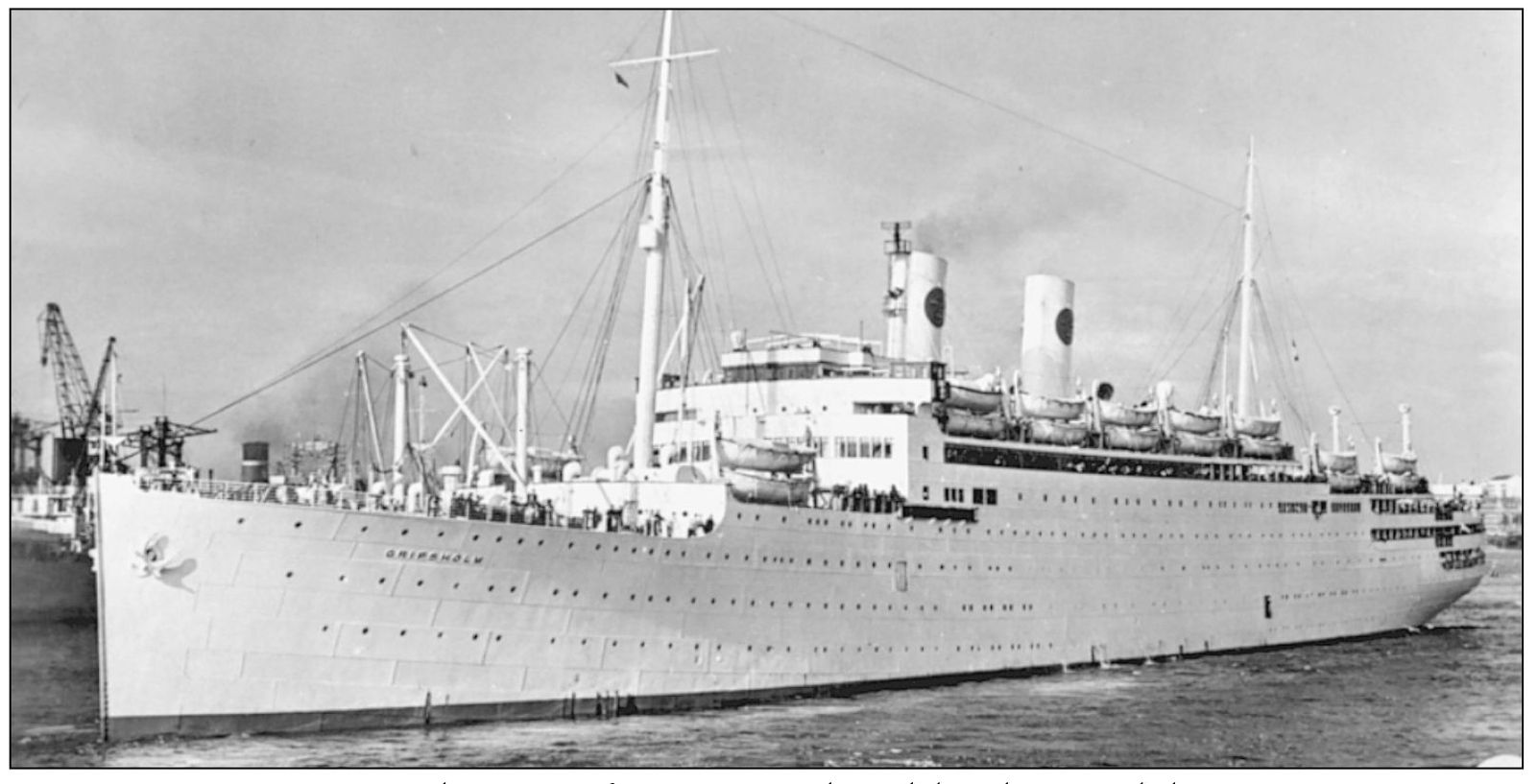

M.S. GRIPSHOLM. According to information gathered by the Swedish American Museum Center, the M.S. Gripsholm was the third ship in the Swedish American line, but the first to be built for the SAL rather than purchased from another steamship company. Because the U.S. government initiated an immigrant quota system in 1924, the Gripsholm was employed more as a cruise ship than as an emigrant transport. The first North American diesel engine motor ship (as opposed to her steamship predecessors), the Gripsholms smokestacks were merely decorative. (Postcard courtesy of Paul Michael Peterson.)

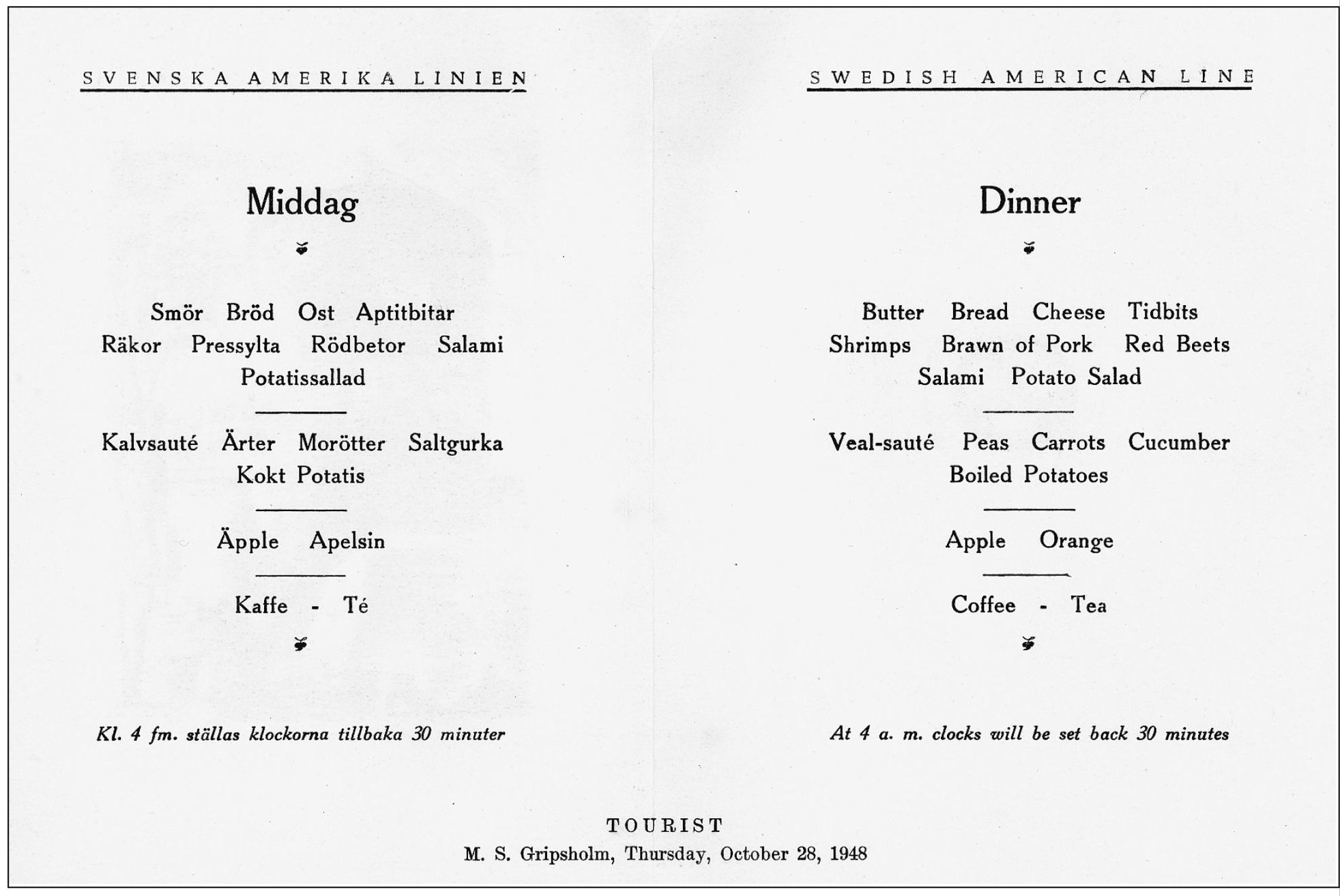

SWEDISH AMERICAN LINE MENU. This tourist menu from 1948 reflects the culinary selections for the dinner or middag meal. (Courtesy of Bruce Peterson.)

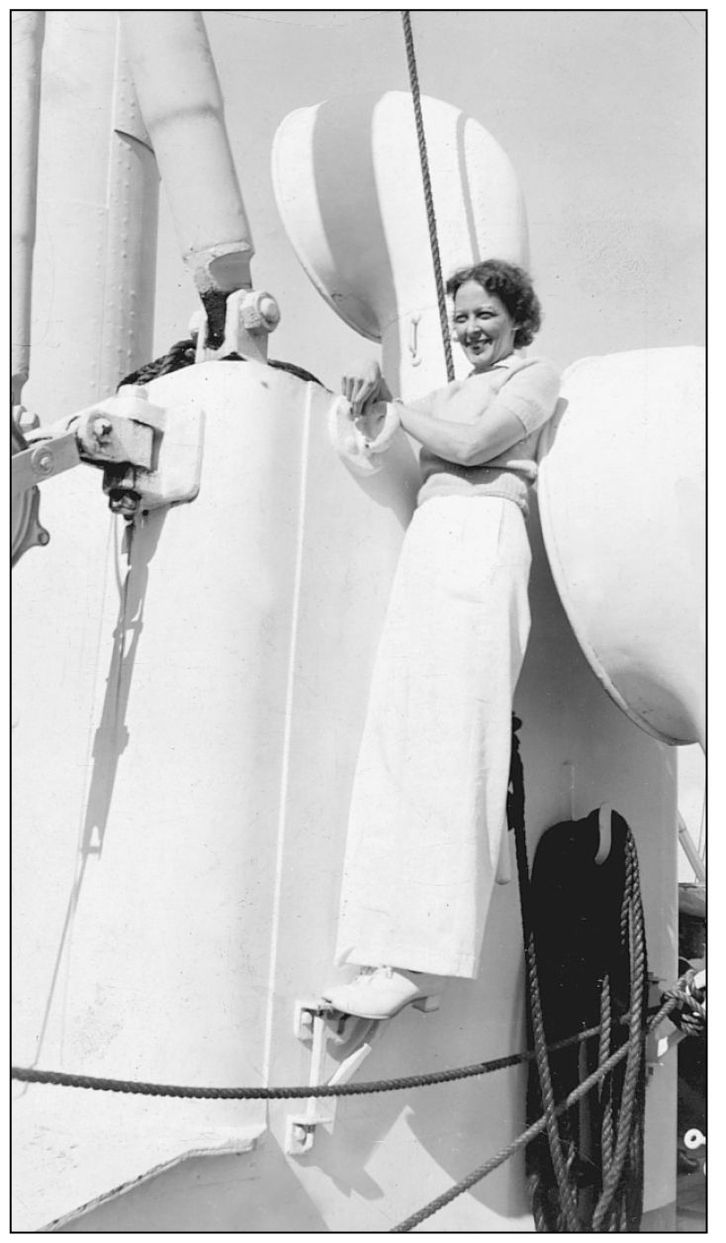

EBBA THUFVESSON. She sailed to America on the last boat out of Norway before 1940. Her husband, Alf (pictured in the back row, center, in the photograph below), traveled from Sweden through Russia and Siberia on a Japanese freighter before reaching America where he worked as a 3-D engraver. Ebba and Alfs daughter, Susan Erickson, presently owns and operates the Sweden Shop on Foster Avenue in Chicago. (Courtesy of Susan Erickson.)