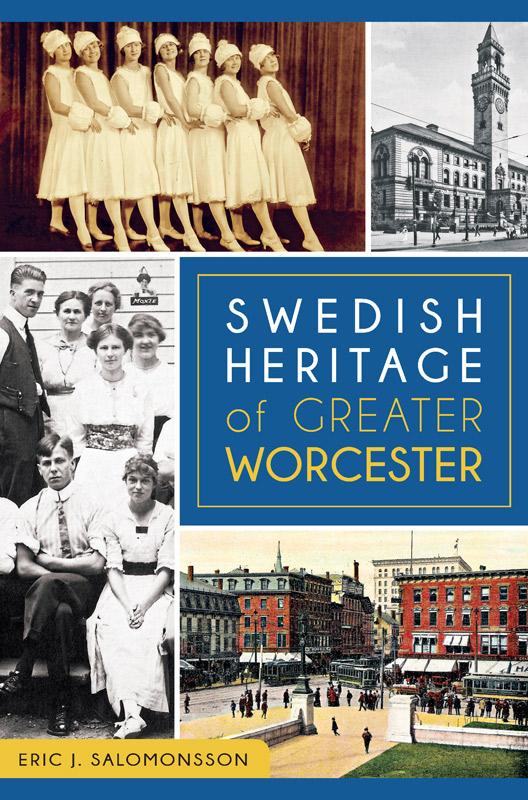

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Eric J. Salomonsson

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.698.2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015951459

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.942.9

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Dedicated to my family, especially my mother, Shirley, who has graciously risen to the challenge of being a Swede by marriage.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Writing a book is a journey during which one meets so many wonderful people along the waya proverbial literary yellow brick road, if you will. Writing history allows one to become the detective. Books, newspapers and ephemera of all types, as well as archives, photographs and maps, become your best and, at times, your only friends. Its a fantastic experience, and I encourage the reader of this book to accept the challenge, be it for history or another passion.

This book is partly a revision and rewrite of a portion of an earlier MA thesis that I had written. Since that time many moons ago, more information has been uncovered, and certain inconsistencies have been corrected and updated as a result. History is never static, and neither is the researcher.

The following people helped to guide and encourage me along this journey; each provided resources and information that have helped make this story a reality. I thank you.

The staff at the Worcester Historical Museum, especially Director William Wallace and Head Librarian Robin Christensen.

Dr. Susan Williams (retired), Fitchburg State College.

Professors Ren Reeves and Benjamin Lieberman, Fitchburg State College.

Nancy Gaudette (retired) and the staff at the Worcester Public Library.

Mott Lynn, head of collections management, Clark University.

The staff of the Worcester Registry of Deeds.

Philip Becker, Massachusetts District No. 2 Historian, Vasa Order of America.

Millie Johnson (deceased), Trinity Lutheran Church.

John Anderson, former mayor of Worcester.

Members of the Worcester Swedish-American community.

Karmen Cook, Ryan Finn and the entire staff of The History Press.

Tom Fox, for your love and support.

INTRODUCTION

The Swedish-American historical narrative has generally become a footnote within the context of the overall American experience. With the exception of interested scholars and novice historians, that narrative is largely unknown to the academic and general public at large. Even among a great many Swedish-Americans today, there is a general lack of knowledge in terms of Swedish-American history.

It is a well-accepted fact that Vikings established a small settlement at LAnse aux Meadows in Newfoundland in the year 1000. The Swedish presence in what would become the United States can be traced back to as early as 1638, when the colony of New Sweden was founded along the shores of the Delaware River. This founding has been the cause of celebrations for Swedes in America since 1888. The roots of the modern-day Swedish-American experience can be traced to the 1845 founding of the first permanent Swedish settlement in the Midwest, when Per Cassel and more than a dozen followers established New Sweden in Iowa. The following year, about 1,200 followers of self-proclaimed prophet Erik Jansson laid claim to Bishop Hill in Illinois, signaling an era of mass immigration. Bishop Hill is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and home to the archives of the Vasa Order of America.

During the antebellum period, the earliest arrivals settled at coastal ports or within the western interior. Eventually, large-scale Swedish immigration began, particularly in the period following the end of the American Civil War. The lure of prime land, as promoted in the Homestead Act of 1862, attracted prospective farmers to areas in the Midwest. Despite the visions of an independent life and the romanticized visions of these immigrant settlements, the environment oftentimes proved hostile. The elements were extreme, often violent. Most of the immigrants were ill prepared either from the burning summer sun or the icy blasts of winter in the great interior. Minnesota, Illinois and Kansas, in particular, housed significant Swedish-American populations whose presence continues to influence the history and culture of the region. Groups or families, settling chiefly in the rural areas of the Midwest, characterized the earliest immigration, and many of these groups established townships that still bear their Swedish names.

TABLE 1. SWEDISH IMMIGRATION STATISTICS, 18511939

| Decade | Total | Annual Average |

| 185159 | 14,774 | 1,477 |

| 186069 | 73,570 | 7,357 |

| 187079 | 80,336 | 8,034 |

| 188089 | 331,071 | 33,107 |

| 189099 | 213,802 | 21,380 |

| 19001909 | 211,929 | 21,193 |

| 191020 | 98,375 | 9,837 |

| 192029 | 95,755 | 9,575 |

| 193039 | 9,133 | 913 |

Source: Figures tabulated from Lars Lindmark, Swedish Exodus, 14547.

As industrialism exploded in America, the demographics of Swedish immigration changed. By the 1890s, the majority of Swedish immigrants had begun to settle within the thriving urban centers of America, particularly in the Northeast. Many were single, skilled male workers attracted by the bustling activity of the age. Single women also came in greater numbers, enticed by an independent lifestyle free from the hierarchy of Swedish everyday life. Many of these adventurous ladies became domestics and servants for those of the upper class. In time, chain migration patterns developed, fueled by kinship links. In these urban centers, of which Worcester is a prime example, the Swedes became one of a host of ethnic groups struggling to maintain cohesiveness within this new tumultuous environment. Numerous Swedish colonies were established, with large settlements in Chicago, Illinois; Jamestown, New York; and Worcester, Massachusetts. By 1910, more than half of Swedish immigrants resided in urban areas, and according to Lars Ljungmark, this pattern has kept pace with the overall process of urbanization in American society. Between 1850 and 1930, more than 1 million Swedes immigrated to the United States; about one-fifth returned to Sweden.

As the Swedish population increased, a network of national and local organizations developed in order to establish group cohesiveness within the American context. This included the foundation of social, fraternal, benevolent and religious institutions of varying denominations. Numerous weeklies and the establishment of Swedish-language publishing concerns helped to knit the local and national community together. By the turn of the twentieth century, the Swedish-American identity, in combination with the influence of American society, revealed both the preservation of fundamental homeland values and the rejection of traditions and practices that had alienated them in Sweden.

Next page