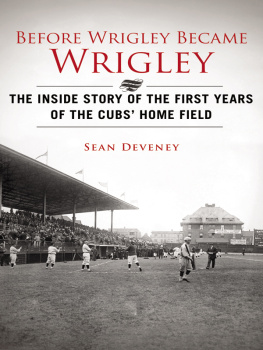

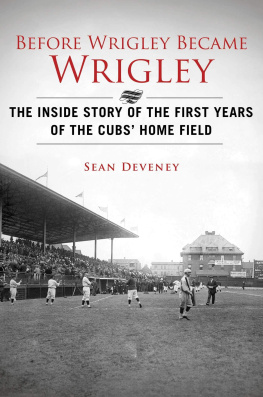

Copyright 2014 by Sean Deveney

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Sports Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Sports Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sports Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Sports Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.sportspubbooks.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61321-648-4

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

The Cubs and the North Side, Day One

F or the Cubs and the teams sitting president, Charley Weeghman, it was the strangest of weeks. It was as though every actor in the drama that had unfolded over the previous two years made some sort of cameo appearance around the teamenemies, rivals, friends, well-wishers, and even peripheral players who had popped up only in tangential roles. The 1916 season was getting underway, but there was no avoiding his confrontations with the recent past. It could all be met with a smile and a wave, now that circumstances had shoved Weeghman into the spot hed long coveted, the leading role as a baseball magnate with the Cubs. But that didnt change the bizarreness. The season opened on the road on April 12 in Cincinnati. It was there, just over sixteen months before, that Weeghmans first run at purchasing the Cubs, aided by Reds owner Garry Herrmann, had fallen apart, because of the obstinance of owner Charles Taft and the negative influence of former Cubs president Charles Murphy. And just four months before in that city, at a happier moment, a deal was hammered out with Taft which ultimately delivered the Cubs to Weeghman.

The Cubs would win their Opening Day game, with George Slats McConnellwho had once been a source of tension between Weeghman and the very Cubs he now ranon the pitchers mound. They would, however, lose their next four and by the time they were ready to return to Chicago for their own home opener eight days after their first game against the Reds, they were just 24 and struggling. But their record didnt much matter, because for the Cubs, April 20, 1916, was destined to go down as a red-letter day in team history. It would be their first game at Weeghmans concrete-and-steel park at Addison and Sheffield on the North Side, the Cubs having deserted their longtime home on the West Side after Weeghman bought the team. Many in Chicago felt that the Cubs belonged to the West Side, that there was some sacrilege in the team playing anywhere but the section of town that had supported them through the wildly successful years just after the turn of the century when the team was the most dominant in all of baseball. But Weeghman aimed to silence doubters quickly. He knew how to hold a celebration, and he did not skimp on this one. Plans were laid for a motorcade to leave from Grant Park, through Chicagos busy downtown Loop district, back up Michigan

Meanwhile, Weeghmans manager, former Cubs great Joe Tinker, was more concerned about the clubs poor start and the fact that many of his players had never performed for so much as an inning at the North Side park. On April 19, while Weeghman was prepping the park with a new section of seating that would fit 3,000 fans along the first- and third-base linesmore than 100 carpenters were hurriedly working to finish the jobTinker called for his players to report for hitting practice at 10:30, allowing his men the afternoon off to find apartments in the city. When rain scotched those plans, Tinker held a strategy session in the team clubhouse until it was dry enough to take some swings, after noon. The fences down the left and right field lines in the park were notoriously short, and, when batting practice started, players sized up the length of the fields. Immediately an effort was started to drive the ball over the barricades. The apartment-hunting, apparently, had to wait.

By Opening Day, all was prepared. The park was sold out, the seats were finished, the Cubs players had at least gotten a look at their new home. The parade, which got underway at 1 PM, proved to be a bad ideathough it was unseasonably warm, even reaching the low seventies, it was rainy, and neither Mayor Thompson nor Governor Dunne showed up. Still, when the group reached the park, an array of fireworks went off, and the procession of players and dignitaries was greeted by thousands of waiting fans. The rooters went wild with enthusiasm, the Daily News reported, for it was the first appearance of Manager Tinker and the Cubs on the local grounds . Cubs rooters with all sorts of noise making implements cheered and greeted the Cubs as if they were world champions.

Maybe a more apt gift was presented to Weeghman by the 25th Ward Democratsa donkey. Weeghman, ever popular around the North Side, was once considered as a Democratic candidate for alderman of the ward. Another four-legged gift came courtesy of one of Weeghmans fellow Cubs investors, meatpacking millionaire J. Ogden Armour, who offered a live black bear cub. The bear would become the teams mascot and would be nicknamed JOA in Armours honor. The donkey wisely galloped under the friendly shelter of the stand on the appearance of the Armour bear.

Well after the appointed time of 3 PM, umpire Hank ODaywho had been the Cubs manager for a season in 1914got the game started. It would be a long one. Cubs starter Claude Hendrix struggled with his control from the beginning, yielding two runs in the first, but the Cubs were able to tie the score in the bottom of the inning by plating two runs off of

For the West Side of Chicago, 1916 marked the first year without professional baseball since 1884. The Cubs were gone and, with them, the major leagues left that huge swath of the city forever. Now, the Cubs would belong to the North Side, which was simply unnatural to most Chicago sports fans. In the Chicago Tribune , just before Opening Day, humorist Ring Lardner offered The North Side Standard Guide, a column he hoped would help introduce West Side fans to the Cubs new home. Lardner poked fun at the array of upscale homes and hotels that had been built along the shore of Lake Michigan on the North Side, as well as the insularity of West Siders.

The North Side is that part of Chicago situate north of the river, west of the lake, south of Evanston and east of Kedzie Avenue. Its accessibility, natural beauties, and mild climate are responsible for its popularity with people who previously have passed their summers in Europe . The North Side is a well-equipped, modern city. It has asphalt and brick pavements, gas and electric lights, artesian water, fire department, well-stocked markets and stores, elegant churches and an increasing number of palatial apartment buildings. It is the fashionable summer resort of Chicago. Visitors find every convenience and luxury. The North Side is

Indeed, the area had developed considerably over the previous decade, but, at the time, the move of the Cubs into what is now known as Wrigley Field represented the most significant event in the history of the North Side, a move that brought the neighborhood to full integration and significance within the city. After 1916, the West Side would never quite be the same. And neither would the North Side, with its shimmering ballpark just blocks from Lake Michigan now occupied by a much-beloved team that was a Chicago institution. Though it was bizarre for Chicagoans in 1916, it didnt take long for the North Side to become synonymous with the Cubs, as has been the case since.