First Published in 2001

by Curzon Press

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2001 Reuben Ahroni

Typeset in Photina by LaserScript Ltd, Mitcham, Surrey

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book has been requested

ISBN 978-0-700-71396-7

ISBN 978-1-315-02860-6 (eISBN)

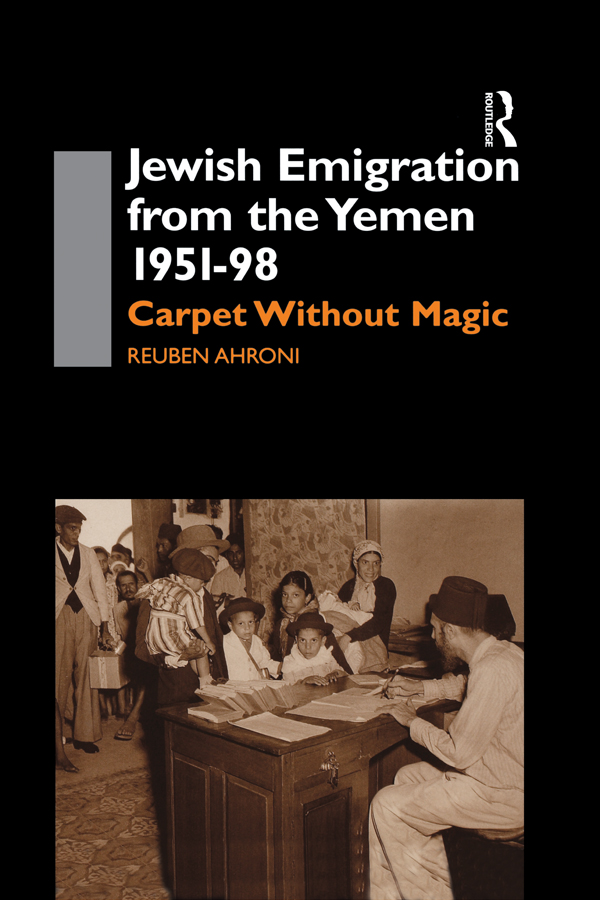

This book is a sequel to my three works on the Jews of the south Arabian peninsula. It was in 1996 that Robin Gilbert of London presented me with a valuable collection of documents and photographs. Gilberts collection has been partially exploited by Dr. Tudor Parfitt (SOAS) for his penetrating study of Yemeni Jewry, The Road to Redemption (E.J. Brill, 1996), which focuses on the years 1900-1950.

The collection had initially belonged to the late Colonel Max Lapides. During his mission in Aden on behalf of the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem, Colonel Lapides had painstakingly preserved and assembled these documents in the hope of publishing an account of his mission. Unfortunately, Lapides died before he had the opportunity to write his book. His immense collection was augmented by Robin Gilbert who, thanks to his knowledge of Arabic and his good relations with the British authorities, served during the years of 1957-1958 as valued associate to Lapides in Aden. For decades, this unique archive was kept intact in Gilberts possession.

The story of the Yemeni Jews who remained in Yemen stands in contradistinction to that of their brethren who emigrated to Israel during Operation Magic Carpet (1949-1951). For one thing, the attitude of the Yemeni remnants towards emigration to Israel was stunningly different. Before and during Operation Magic Carpet, Yemeni Jews who were motivated by messianic frenzy, poured continuously into Aden, en route to Israel. They came on their own in overwhelming numbers, many of them on foot, undeterred by the prospects of the trials and tribulations which they knew would await them in the course of their travels. They arrived in Aden half-starved, destitute, and emaciated. Despite these and other inconveniences such as the stifling heat of the Aden camp, the gale-force winds, and the sand storms so characteristic of the Arabian desert, the Yemeni Jews hardly complained. With great anticipation, they awaited the day when they would be flown to Israel on eagles wings, as promised in the Hebrew Scriptures. They were very grateful for that privilege.

In contrast, the Yemeni Jewish remnants displayed a strong hesitation, if not reluctance, to leave Yemen. Despite the immense efforts exerted by the Aden Jewish Community Council and the Jewish Agencys representatives to prod them through letters, promises of free transportation and other monetary incentives, they remained ambivalent about emigrating to Israel. Thus, since Operation Magic Carpet and until 1962 the year of the coup dtat which brought about the elimination of the autocratic Imamic regime in Yemen and the closing of the Yemeni gates for Jewish emigration only some four hundred Yemeni Jews heeded the call to emigrate to Israel. It is for this reason that I have subtitled the present study Carpet Without Magic. A red carpet was indeed spread before the Yemeni Jewish remnants, but the magic was no longer there.

Having written the chapters pertaining to Lapides mission, namely until 1962, I decided to extend the study to the last stages of the saga of the Yemeni Jews. The story of the Yemeni Jewish remnants, particularly during the years 1980-1996, is also quite exceptional. Rarely have so few triggered so much interest on the part of so many Western governments and humanitarian organizations.

It is a great honor to be asked by Robin Gilbert to write this book, thus bringing the dream of Lapides to fruition. I feel immensely indebted to them both, particularly to Gilbert who graciously entrusted me with his precious collection. Throughout the writing of this book, I kept in close contact with him; the enthusiasm with which he greeted the work has been a constant source of encouragement. I am also indebted to Dr. Tudor Parfitt for having recommended me in the first instance to Gilbert.

The Appendix to this book features a selection of letters and documents from the Lapides-Gilbert collection. Inevitably, it has been necessary to make hard judgments about which documents should be included in this selection. I strove to include a wide variety of materials, reflecting the major issues that confronted Lapides and Gilbert during their mission in Aden. Regrettably, considerations of space excluded a great deal of excellent material.

All major works cited in the book can be found in the Bibliography. Diacritical marks have been used in transliterating Arabic and Hebrew names and uncommon words. They have been omitted, however, in many instances where the word or its adjectival form is in common English usage. I have chosen to use the current academic term Yemenis) (instead of Yemenite(s)) to refer to the people of Yemen Jews and non-Jews alike unless it appears otherwise in citations.

I wish to acknowledge the abundant and varied assistance which I have received from various individuals; their names are too numerous to cite individually. I would, however, like to record my indebtness to the following prominent members of the Adeni Jewish community in London, who faithfully and unfailingly supported my studies on the Jews of the south Arabian peninsula: Simon and Gabriel Shalom; Simon and Geulla Mahalla; Yona and Joseph Mansoor; Uri and Raphael Shalom. I am thankful to Joseph Galron and Dona Straley of the Ohio State University libraries, who patiently assisted me in locating the more recondite sources relating to my research. I am also grateful to the late Gabri Shalom who provided me with valuable information regarding life in Aden during the 1950s.

I would also like to acknowledge with thanks the encouragement and support which I have received from the following Ohio State University units: the College of Humanities, the Melton Center for Jewish Studies, the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, and the Middle East Center.

Thanks are also due to the Frank Nutis Foundation, and to the Israeli Association for Society and Culture, Documentation and Research, particularly to its president Ovadiah Ben-Shalom, for allowing me to rummage through the Associations rich archives and for the generous support extended to me. Above all, many thanks are due to Rachel, my wife, for helping me in so many ways.