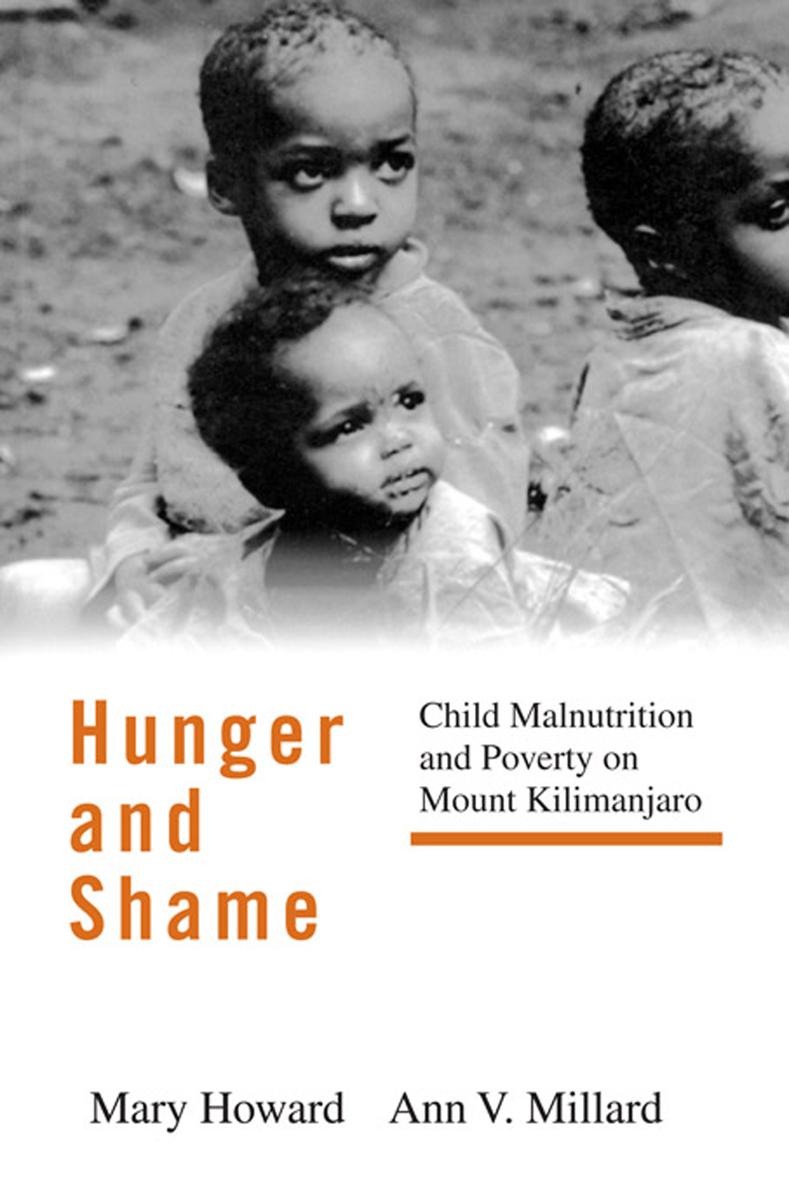

Hunger and Shame

Hunger and Shame

Poverty and Child Malnutrition

on Mount Kilimanjaro

Mary Howard and Ann V. Millard

Published in 1997 by

Routledge

711 Third Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Published in Great Britain by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park

Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Copyright 1997 by Routledge

The text was set in Minion.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Howard, Mary Theresa.

Hunger and shame: child malnutrition and poverty on Mount Kilimanjaro / Mary Howard and Ann V. Millard.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-415-91613-5 (hc : alk. paper). ISBN 0-415-91614-3 (pbk. alk. paper)

1. Malnutrition in childrenTanzaniaKilimanjaro Region.

2. Chagga (African people)Nutrition. 3. Kilimanjaro Region (Tanzania)Economic conditions. 4. Kilimanjaro Region (Tanzania) Social conditions. 5. Chagga (African people)Economic conditions. 6. Chagga (African people)Social conditions. I. Millard, Ann V.

II. Title.

RJ399.M26H69 1997 | 96-46937 |

363.8'2'0967826dc21 | CIP |

Illustrations

Figure 1 | Location of Mt. Kilimanjaro |

Tables

Foreword

Robert B. Edgerton

It is self-evident that the quest for food is crucial for all living organisms, humans very much not excepted. Most of our ancestors who lived by hunting and gathering usually managed to feed themselves reasonably well. It was with the advent of the cultivation of food crops and reliance on cereal grains that malnutrition became a widespread problem. Even so, rising fertility led to such population growth that there are now some six billion people on earth, fully one billion of whom suffer from major forms of malnutrition (Jelliffe and Jelliffe 1989:2).

Hunger, malnutrition, and starvation have not escaped the often pained scrutiny of anthropologists as they have described the lives of people throughout the world. They have written about subsistence strategies, the sacralization of food, and the dreadful consequences of prolonged hunger. This work is fundamental to our understanding of the evolution of human cultures just as it is to the problems of the contemporary world. Yet few of these works leave so vivid a mark as Hunger and Shame, by Mary Howard and Ann V.Millard.

The book is a report about malnutrition among the Chagga of Tanzania, a people who live on the southern slopes of beautiful Mt. Kilimanjaro. The natural beauty of their world hides the dismal reality that their rate of child malnutrition is among the highest in the country, itself one of the poorest in the world. We first meet the Chagga in the mid-1970s, when they were still suffering the effects of a profound famine that had struck the area. After nearly two decades, famine had ended but malnutrition had ravaged many poor families among this often prosperous African people. We are forced to meet parents who cannot feed their children or themselves and to visualize stunted bodies tormented by diseases involving malnutrition. The filth of their urine-soaked living quarters, their ragged clothing, and their dead eyes make an unforgettable impression. Much of the book's value lies in the impact of these images of human misery as the physical pain of hunger is joined by the sense of shame and loss of dignity that such poverty brings.

The book is more than a vivid introduction to malnutrition, shame, and death. It also provides a detailed analysis of the meaning of poverty among the Chagga and of the economic and political factors that have so weakened the kin networks that poor Chagga were earlier able to rely upon. Population growth and land shortage are obvious contributors, but the dichotomy between rich and poor is also a function of access to modern education, creating an enduring gap between rich and poor. Wage labor is another potent factor. Many men must migrate in search of wage-paying employment, leaving their wives to care for their farms and their children, a burden that leaves some women too exhausted to do either one well. More-subtle aspects of Chagga culture contribute to the plight of the malnourished as well. Finally, we are introduced to NURU, the Nutrition Rehabilitation Unit established among the Chagga in 1972. Paid for by private American funds and staffed by doctors from the United States and Europe, NURU provides an instructive example of the cultural complexities that must be confronted if nutrition rehabilitation is to succeed.

Half a century ago, a young anthropologist named Audrey Richards wrote a book entitled Land, Labor, and Diet in Northern Rhodesia, which examined nutrition in an African society. Since Richards wrote, the ravages of malnutrition in Africa are worse, not better. Hunger and Shame forces us to confront the problem, and while it offers no easy solutions, it opens the door to better understanding and, not least, to greater compassion.

preface

Reproduction, Social Relations, and History: Approaches to Child Malnutrition

Ann V. Millard and Mary Howard

The entry of Chagga farmers into coffee production is a contested part of their history. Around the turn of the century, the colonial regime coerced Chagga to work as laborers on Europeans plantations and blocked their entry into competition as coffee producers. Nonetheless, coffee was to become the major cash crop of Chagga farmers, who made it important to the national economy as well.

One story told on Mt. Kilimanjaro says that a Roman Catholic priest first gave coffee seed to the Chagga people, who thus began their own coffee plantations. Another version of the story focuses on a high-ranking Chagga official who privately bought seed from an Italian settler and began a farm, later to sell seed to other officials and the chief.

In the first version, the main actor is a European missionary taking the role of a generous interventionist who refused to favor the economic interests of European plantation owners. The story characterizes Chagga farmers as depending on European leadership for the key to their future. The second version depicts the Chagga as controlling their own destiny and successfully adopting a European cash crop while thwarting the monopolistic maneuvers of European farmers and other colonialists.

Illustrations

Illustrations Tables

Tables preface

preface