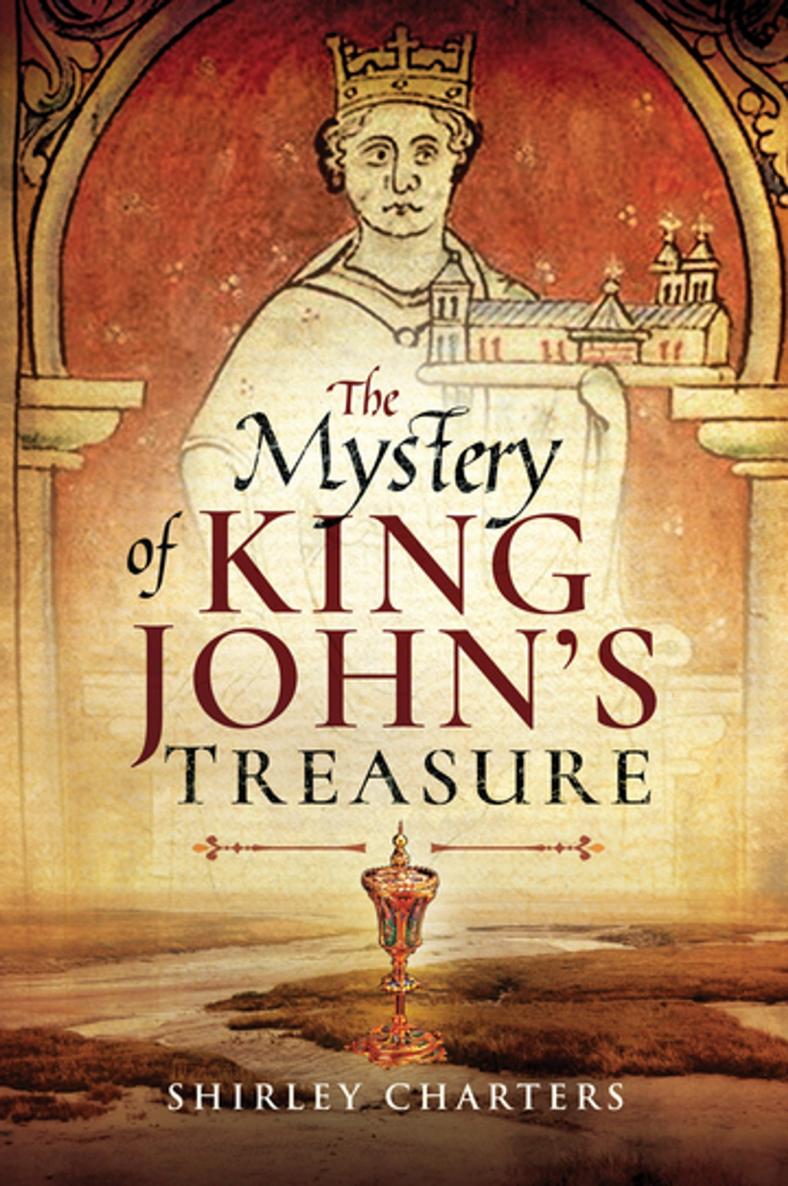

The Mystery of King Johns Treasure

The Mystery of King Johns Treasure

Shirley Charters

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

PEN AND SWORD HISTORY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Shirley Charters, 2018

ISBN 978 1 52671 549 4

eISBN 978 1 52671 551 7

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52671 550 0

The right of Shirley Charters to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword

Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery,

Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways,

Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press,

Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When,

Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

For my son Charlie

who has for so long, cheerfully and helpfully put up with

my interminable musing upon King John.

Preface

King Johns cup is a fifteen-inch high, silver-gilt, enamel and bejewelled goblet that resides in the Museum of Kings Lynn on the Norfolk coast of East Anglia (front cover). It is the oldest and one of the finest pieces of secular medieval English craftsmanship to still exist. For centuries, it was believed to have been a piece of Johns vast treasure trove which shortly before his death was supposedly lost in the marshes of the Wash, and which someone, somehow, somewhere, retrieved. However, it has now been shown to have been made in the mid-1300s, more than a hundred years after his death.

First recorded in the Hall Book of Kings Lynn in 1548, the cup was listed as the prime item of plate to be delivered to the then mayor. Then, as happens in so many centuries of history, the passage of time subsequently wound Johns name around it until it became accepted. However, if the cup has a misguiding title, more wishful thinking than reality, then the inaccuracy inevitably leads on to the thought that perhaps the whole story of King Johns lost treasure might itself be similarly questionable. Or would it?

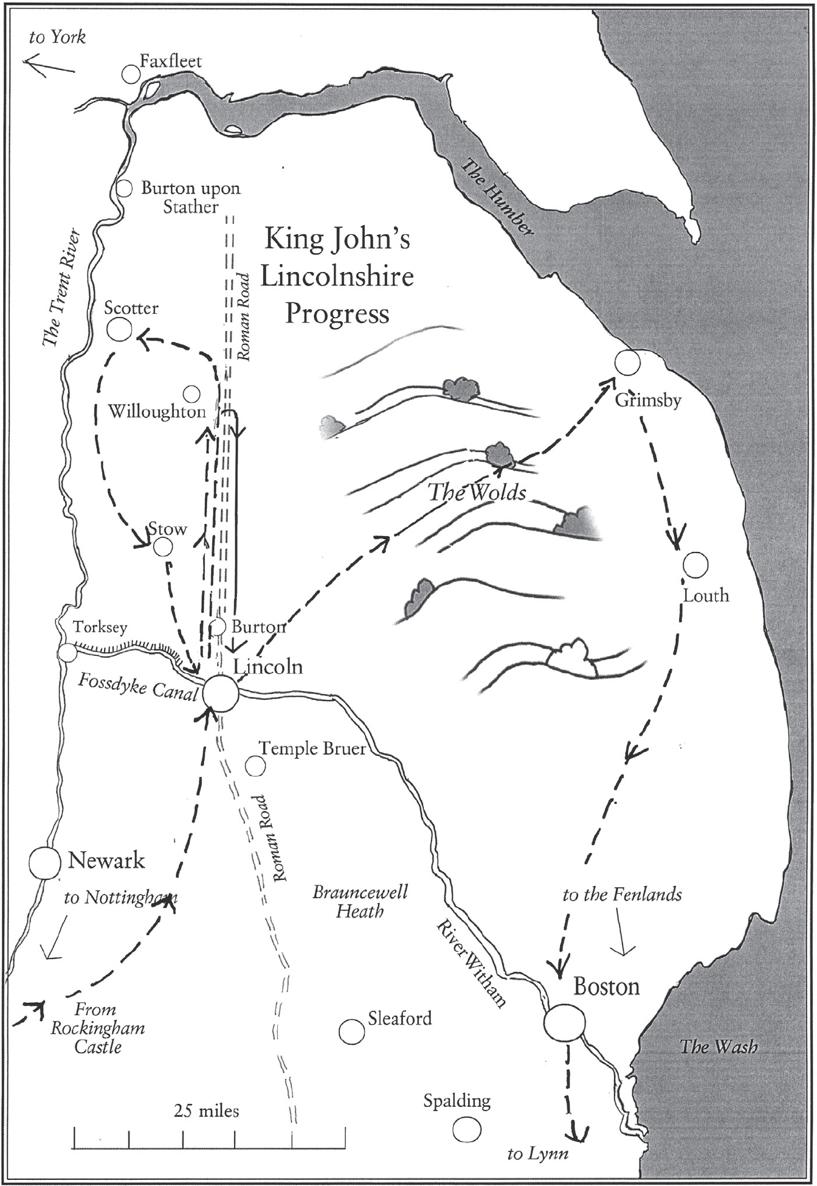

Over the past eight hundred years, there have been endless folk tales, academic papers, false leads and vastly expensive explorations concerning the mystery of the treasure. Lost, when it seems, he was taking a secret short-cut across the Fenlands of East Anglia known only to certain local guides, and when the crown jewels of England and ... all the things he most valued ... were sucked into the unfathomable morass of the Wash. But so, far nothing has ever been found.

Nevertheless, the quest has continued and has been looked into through many and varied magnifying glasses; a search so wonderfully tempting for archaeologists, for readers of monthly metal-detecting magazines and for online valuers of recently discovered medieval artefacts.

Every year now in Britain more than seventy thousand finds both large and small are uncovered. Think of the recent discoveries of the Tudor hoard of jewellery hidden in a Cheapside cellar, or the Viking gold ornaments found in a Staffordshire field, or the cache of gold and silver coins dug up from under a busy street corner in Cambridge. These were all surprise finds, happened upon, and made with no knowledge of what lay hidden below the thick layers of history.

But the search for Johns lost treasure is quite different. The contents of the treasure are known from contemporary lists. And the designated location of the loss, is the Fenland of East Anglia. What more lead for a search could one ask for?

A hundred years ago, the pace of that search quickened. Shortly before the First World War, Lord Northcliffe, proprietor of the Daily Mail formed a syndicate, the Wash Committee, to obtain licences and make Fenland searches of nearly one and a half thousand acres. Then in the Thirties an American professor of John Hopkins University set up The Fen Research Ltd. Company, with a backing of 40,000 to search a further 5,500 acres. After the Second World War, an engineering company, Evershed and Vignoles, followed. They were designers of earth-testing instruments and they moved in with their resistivity survey equipment to take many thousands of readings, working over several years. Nottingham University followed them making bore-hole tests. And in parallel, there has been a continuing flurry of private explorations by hopeful dowsers and detectorists. Many hundreds of thousands of pounds have been spent, yet always without success.

Why has there has been no hint, no sign, no evidence at all of Johns treasure, no fragment of a knights armour, no precious jewel, no golden chalice or crown from Englands crown jewels, no stirrup from a saddle, or heraldic pendant from a bridle or barrel of silver short-cross coins with his image on them? And why indeed, did a Plantagenet King of England find himself with the crown jewels and all of his vast treasure in such an inhospitable place as the medieval wilderness of the Fenlands?

Here lies a mystery, hidden in a strange landscape, put to sleep by time, which this book now resolves; unravelling the answer from the spiders web complexity of the last ten days of Johns life.

CHAPTER 1

Sunday 9 October 1216; Late Afternoon at Lynn

John is late arriving towards the port of Lynn. It has been an awkward days ride from Spalding in Lincolnshire; starting just after cockcrow and skirting some forty miles right round that seemingly endless, demon-ridden Fenland. Hes chilled by nagging gusts of an easterly wind that whips up unimpeded from the sea. It pierces the marrow of his bones. He can taste saltiness in the bite of it as he dismounts, dragging himself off his horse with the heaviness of a man burdened by woes of more years than he has managed to live. Oh God, so much yet to be done so much still left undone. Does he already sense that the Fates in charge of his thread of life have gathered together, Clotho spinning and Lachesis measuring? Does he already suspect their final conclusion: that his woes will remain unresolved, at least they will remain unresolved by him? For in ten days time, he will be dead.