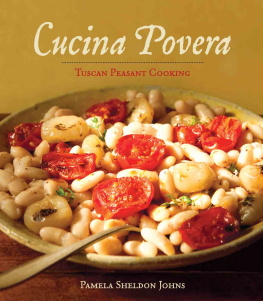

Cucina Povera

The Italian Way of Transforming Humble Ingredients into Unforgettable Meals

Giulia Scarpaleggia

Photographs by Tommaso Galli

Artisan | New York

To my family

Contents

Cooking from the Garden

Offal and Affordable Cuts of Meat

Recipes from the Farmyard

Italian Pesce Povero

Dairy-Based Meals

Plant Proteins

Staples from the Mountain Regions

Making the Most of What Youve Got

Making Do for Cakes, Tarts, Puddings, and Cookies Too

Breads, Stocks, and Sauce

Introduction

Cucina povera, Italian peasant cooking, is the way people have been cooking in Italy for centuries, in both the cities and the countryside. Cucina povera is not just a unique approach to cooking and ingredients; its the highest expression of the Italian arte dellarrangiarsi, the art of making do with what youve got.

Traditional cucina povera dishes are immediately recognizable from some common traits: the use of humble ingredients, seasonal vegetables, and simple cooking techniques, along with a healthy dose of imagination. This culinary approach may be ancient, but it is still relevant today; it is a way of cooking that transforms simple ingredients into hearty meals that are more than the sum of their parts.

Italian cucina povera relies on basic, affordable ingredients that are available no matter where you live, from a loaf of sturdy bread to different types of dairy and cheese, as well as seasonal vegetables, grown in your garden or obtained from a local market. Leftovers of all sorts, from the remains of a Sunday roast to scraps from homemade fresh pasta, are reinvented to make a second (or even third) meal that is just as tasty and nutritious as the original one. Day-old bread and leftover pasta, rice, and boiled meats are transformed with inventiveness and an innate sense of taste into treats like fried arancine, spaghetti frittata, beef stew with onions, and meatballs. Cucina povera brings excellent value to your cooking, and who doesnt need that?

Meat is eaten only on rare occasions. Rather, the cuisine is centered around dishes with fish or vegetable and plant proteins such as chickpeas and fava beans, along with basic ingredients like chestnuts, potatoes, and pasta. These ingredients may be simple, but when you use them the Italian way, you will never feel like you are missing out. And some of the most popular Italian dishes, those that are some of the best examples of cucina povera, require only a few ingredients. Think of cacio e pepe or polenta.

Cucina povera employs some clever strategies to make the most of what you have in your pantry. Stale bread soaked in water or in a tasty vegetable stock makes soups more filling and nutritious; Tuscanys hearty ribollita and Apulias pancotto both incorporate this trick. Breadcrumbs become a filling for stuffed vegetables, another layer in a cod and potato bake, or, when fried until golden, a crisp, tasty seasoning for orecchiette. A boiled chicken will give you more than one meal: the next day, toss the shredded meat into a colorful salad with radicchio and pickled vegetables, and then use the golden stock to cook risotto or passatelli, or to make stracciatella. The most important principle of Italian cucina povera is an economical, waste-not approach, which is still practiced today in most Italian households.

There are recipes for weeknight suppers and Sunday gatherings, recipes to celebrate the season with a group of friends, and recipes youll find yourself making time and time again as they become new favorites. With their short lists of affordable ingredients and simple cooking techniques, cucina povera dishes easily fit into our modern lives, with a traditional yet contemporary attention paid to sustainability, budget, and inclusiveness, with dishes that are naturally gluten-free, vegetarian, or vegan.

Cucina Povera in Italian History

Nowadays Italian cooking is often viewed as fragmented into different regional cooking styles, based in part on the local preference for particular ingredients, such as butter rather than olive oil (or vice versa), meat over fish, and pasta rather than polenta. These differences are influenced both by availability and historical political domination: Arab and then Spanish in the South, Austrian and French in the North. There is a common ground, though, that characterizes all Italian cuisine, that makes it unique and recognizable, and that is an allegiance to the principles of cucina povera.

Historically, Italian cucina povera was considered the cuisine of poor people, as opposed to the cuisine of the elite. Throughout time, different cuisines were classified as cucina povera: the cuisine of the countryside, that of poor mountain people, that of nomad shepherds, and that of city dwellers struggling to make ends meet in an impoverished environment. In cucina povera, you can find recipes, ingredients, and techniques that go back to medieval times or even before, as well as more recent recipes that sustained people through the hardship of postwar Italy.

Every Italian region has its own traditional ingredients and foods: polenta and rice are the staples of the cucina povera in the North of Italy, where dishes such as risi e bisi and polenta concia are a source of pride and identity. Tuscany has its pane sciocco, a bread made without salt, used to create quintessential Tuscan recipes such as pappa al pomodoro, panzanella, and ribollita. Dried pasta, legumes, and vegetables are staples in the Southern diet: for example, pasta e fagioli in Naples and lagane e ceci in Basilicata. In big cities where butchering traditions have always had a significant role, the cucina povera revolves around the quinto quarto, the affordable cuts of meat left after the slaughtering, including heads, tails, and all the innards. So in traditional trattorias, you still find hearty, gutsy dishes such as rigatoni alla vaccinara in Rome, along with trippaa fixture also in Milan and in Florenceand liver stewed with onions in Venice.

My Tuscan Roots

Tuscanys cucina povera is in my blood. I was born in the Tuscan countryside and raised in a traditional tight-knit family, with a mother and a grandmother who applied the principles of the cuisine to our everyday meals. My mother, Anna, and my grandmother Marcella informed the way I now cook for my family.

My grandma, who was also born and raised in the Tuscan countryside and grew up during World War II, taught me that a well-stocked pantry is not only the starting point of almost every meal but also a source of pride and security. In her home, any leftover pieces of stale bread were religiously collected in a cotton bag that hung behind the kitchen door, to become the basis of a stuffing for green peppers, a topping for roasted vegetables, or, in summer, panzanella.

Next page