PRAISE FOR

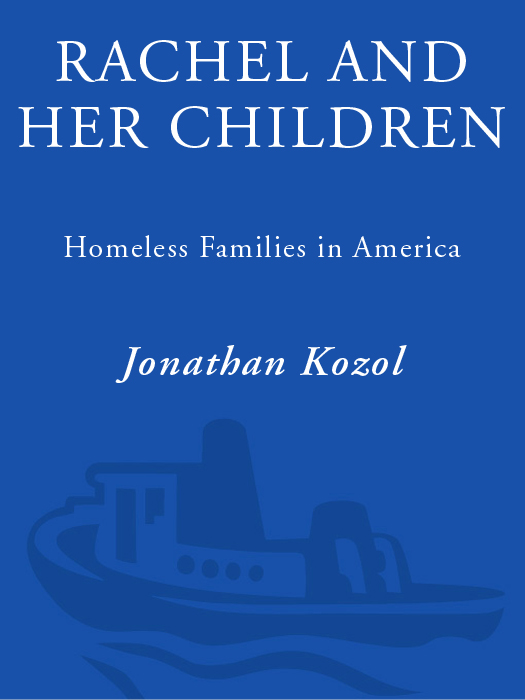

Rachel and Her Children

Extraordinarily affecting A very important book. To read and remember the stories in this book, to take them to heart, is to be called as a witness.

The Boston Globe

A book that should be read by every middle-class (and any class) American pulls us, willingly or not, straight into the heart of what it means to be a homeless family in America.

San Francisco Chronicle

Bitterly eloquent.

Newsweek

Compelling, moving, eloquent An extended tour of Hell.

Los Angeles Times

Kozol, todays most eloquent spokesman for Americas disenfranchised, won a National Book Award for Death at an Early Age, and this new work is every bit as powerful. Reading it is a revelation. A searing trip into the heart of homelessness.

Chicago Sun-Times

Kozol has written it down, in a clear, passionate, and horrifying book that strips away all comfortable illusions we like to maintain about the homeless.

Boston Herald

Gripping desperate stories of more than a dozen families and their children Kozol bears witness to their suffering and to the inhumanity of the system created to help them.

The Atlanta Journal and Constitution

Also by Jonathan Kozol

DEATH AT AN EARLY AGE

FREE SCHOOLS

THE NIGHT IS DARK AND I AM FAR FROM HOME

CHILDREN OF THE REVOLUTION

ON BEING A TEACHER

ILLITERATE AMERICA

SAVAGE INEQUALITIES

AMAZING GRACE

ORDINARY RESURRECTIONS

THE SHAME OF THE NATION

For Yvonne Ruelas

Beverly Curtis

Michael Stoops

CONTENTS

PART ONE:

PART TWO:

PART THREE:

TO THE READER

Homeless people in this book are not identified by their real names. This decision is dictated in part by the wishes of the people interviewed. It is commonly believed by residents of homeless shelters, including hotels, that they render themselves subject to retaliation or eviction by authorities if they speak with candor to a writer or reporter. For this and other reasons, many have asked me to disguise sufficient details (time, date, place of interview, hotel room, floor number, physical features, exact ages of children in a family, and other identifying details) to assure their anonymity.

In some instances, conversations are condensed and events told to me out of order are resequenced. Dialogue is reconstructed from notes or edited from tapes. Apparent inconsistencies or contradictions that occur from time to time, especially in stories told by children, are allowed to stand. Corrective information is provided in the notes.

All events described to me within this book took place in the locations indicated. All events that I describe firsthand took place in my presence. All words spoken by shelter residents of New York City in this book were spoken by residents of the shelters I describe.

Ordinary People

H e was a carpenter. She was a woman many people nowadays would call old-fashioned. She kept house and cared for their five children while he did construction work in New York City housing projects. Their home was an apartment in a row of neat brick buildings. She was very pretty then, and even now, worn down by months of suffering, she has a lovely, wistful look. She wears blue jeans, a yellow jersey, and a bright red ribbon in her hairfor luck, she says. But luck has not been with this family for some time.

They were a happy and chaotic family then. He was proud of his acquired skills. I did carpentry. I painted. I could do wallpapering. I earned a living. We spent Sundays walking with our children at the beach. They lived near Coney Island. That is where this story will begin.

We were at the boardwalk. We were up some. We had been at Nathans. We were eating hot dogs.

Hes cheerful when he recollects that afternoon. The children have long, unruly hair. They range in age from two to ten. They crawl all over himexuberant and wild.

Peter says that they were wearing summer clothes: Shorts and sneakers. Everybody was in shorts.

When they were told about the fire, they grabbed the children and ran home. Everything they owned had been destroyed.

My grandmothers china, she says. Everything. She adds: I had that book of gourmet cooking

What did the children lose?

My doggy, says one child. Her kitten, born three days before, had also died.

Peter has not had a real job since. Not since the fire. I had tools. I cant replace those tools. It took me years of work. He explains he had accumulated tools for different jobs, one tool at a time. Each job would enable him to add another tool to his collection. Everything I had was in that fire.

They had never turned to welfare in the twelve years since theyd met and married. A social worker helped to place them in a homeless shelter called the Martinique Hotel. When we meet, Peter is thirty. Megan is twenty-eight. They have been in this hotel two years.

She explains why they cannot get out: Welfare tells you how much you can spend for an apartment. The limit for our family is $366. Youre from Boston. Try to find a place for seven people for $366 in New York City. You cant do it. Ive been looking for two years.

The city pays $3,000 monthly for the two connected rooms in which they live. She shows me the bathroom. Crumbling walls. Broken tiles. The toilet doesnt work. There is a pan to catch something thats dripping from the plaster. The smell is overpowering.

I dont see any way out, he says. I want to go home. Where can I go?

A year later Im in New York. In front of a Park Avenue hotel Im facing two panhandlers. It takes a moment before I can recall their names.

They look quite different now. The panic I saw in them a year ago is gone. All five children have been taken from them. Having nothing left to lose has drained them of their desperation.

The children have been scatteredplaced in various foster homes. White children, Peter says, are in demand by the adoption agencies.

Standing here before a beautiful hotel as evening settles in over New York, Im reminded of the time before the fire when they had their children and she had her cookbooks and their children had a dog and cat. I remember the words that Peter used: We were up some. We had been at Nathans. Although I am not a New Yorker, I know by now what Nathans is: a glorified hot-dog stand. The other phrase has never left my mind.

Peter laughs. Up some?

The laughter stops. Beneath his street-wise manner he is not a hardened man at all. It means, he says, that we were happy.

By the time these words are printed there will be almost 500,000 homeless children in America. If all of them were gathered in one city, they would represent a larger population than that of Atlanta, Denver, or St. Louis. Because they are scattered in a thousand cities, they are easily unseen. And because so many die in infancy or lose the strength to struggle and prevail in early years, some will never live to tell their stories.

Not all homeless children will be lost to early death or taken from their parents by the state. Some of their parents will do better than Peter and Megan. Some will be able to keep their children, their stability, their sense of worth. Some will get back their vanished dreams. A few will find jobs again and some may even find a home they can afford. Many will not.