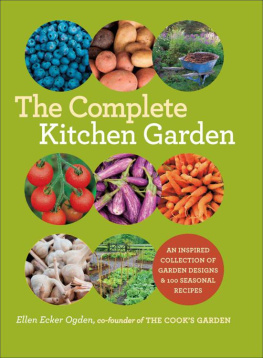

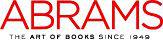

The Complete Kitchen Garden

Published in 2011 by Stewart, Tabori & Chang

An imprint of ABRAMS

Text copyright 2011 Ellen Ecker Ogden

Illustrations copyright 2011 Ramsay Gourd

Photographs copyright 2011 Ali Kaukas

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ogden, Ellen.

The complete kitchen garden / Ellen Ecker Ogden.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-58479-856-9 (alk. paper)

1. Kitchen gardens. 2. Vegetable gardening. I. Title.

SB321.O335 2010

635dc22

2010032448

Editor: Dervla Kelly

Designer: Pamela Geismar

Production Manager: Ankur Ghosh

The text of this book was composed in Scala, Archer, and Sketch Block

Stewart, Tabori & Chang books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

115 West 18th Street

New York, NY 10011

www.abramsbooks.com

Dedicated to my children Molly and Sam,

the next generation of gardeners.

Contents

From Art to the Kitchen Garden

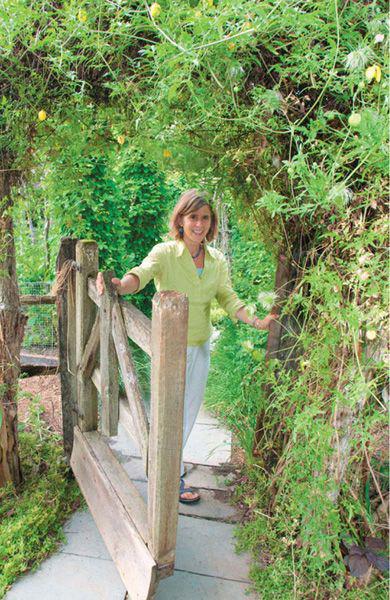

I planted my first garden in 1980, marking the perimeters with four sticks and a ball of twine. With a sharp-edged spade, I removed a thick layer of rugged turf, dug up the stony soil to create a reasonably loose pile, then shoveled on some compost. Using the same four sticks and twine, I measured out long, straight rows before planting seeds for basil, lettuce, and arugula. I sprinkled them with water and walked away. I was fresh out of art school and just starting a small design business. I thought this might be a good way to feed myself.

I would be stretching the truth if I said the garden thrived. There was a constant battle with the weeds, and the garden hose didnt quite reach, so the plants were frequently thirsty. Yet the thrill of dashing to the garden just before dinner to clip a few leaves of frilly Lolla Rossa and crimson Bulls Blood beet greens for my salad kept me at it. And that thrill gave way to a feeling of pride in growing my own food. I reveled in fewer trips to the grocery store in favor of wandering into the garden with bare feet and a harvest basket. This set in motion the creation of a larger patch the following year, with my husband, and soon our garden covered almost an acre. Since we could buy tomatoes, corn, and cucumbers at the market, but couldnt always find tender loose-leaf lettuce, baby spinach, piquant sweet basil, or savory fennel leaves for spicing up our salad bowl, we focused on growing crops that were hard to find, with a fragile shelf life, so the time between the garden and the table was always kept to just a few minutes before dinner.

The garden took up more and more of my time; eventually, instead of making art on a canvas, I began to think of myself as a food artist. I built a collage of lettuces splashed with dabs of red orache, fronds of chervil, and rosettes of claytonia. Seeds and plants were my paintbrush, as I combined waves of bronze-tipped lettuce with swirls of magenta radicchio and spikes of blue-green kale, highlighted with accents of brilliant orange nasturtiums. The long, straight rows gave way to fancy arcs and geometric triangles, and I began to look for inspiration from classic European-style kitchen gardeners, with recipes to match.

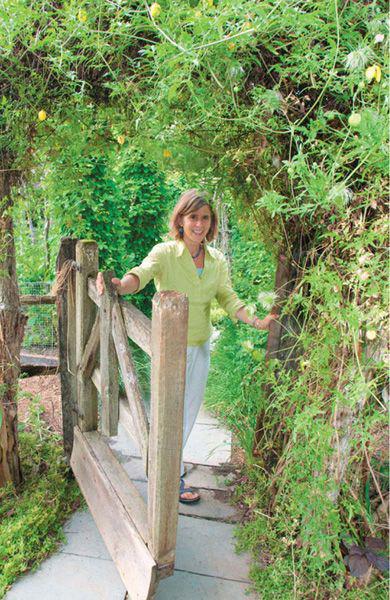

It wasnt long before my husband and I were in search of a wider variety of ornamental edibles and began to import seeds for chicories and onions from Italy, mache from Switzerland, along with heirloom lettuce and mesclun from France. Along the way, we discovered seventeenth-century seed recipes for mesclun mixes originally created by French and Italian gardeners for their own kitchen gardens, with fitting names that reflected their origins: Provencal, Misticanza, and Nicoise. We couldnt get enough of them, and began to order seeds in five-kilo bags. Clearly, our garden project had progressed well beyond growing a few things to eat. So in 1984, we cofounded a seed catalog called The Cooks Garden, to share our love of European and American heirloom lettuce and salad greens with other gardeners (as well as to justify our buying habits). At first it was just a seasonal businessduring the winter, seed envelopes were packed at the kitchen counter, and during the summer, our weekend farm stand overflowed with produce from our gardens.

The seed catalog started as a two-page listing featuring close to 150 different types of exotic lettuce and fancy salad greens with wonderful foreign namessuch as Reine des Glaces, Merveille de Quatre Saisons, Brussels Winter Chervil, and Osaka Purple Mustardthat were relatively unknown to American gardeners at the time. Yet we quickly discovered that there were other gardeners who, just like us, were hungry for something out of the ordinary and who shared the desire to plant a vegetable garden with a style that reflected a conscious, connected lifestyle, rather than simply a source of food.

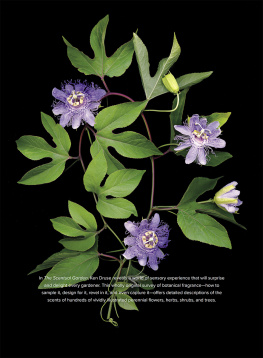

A kitchen garden may be just a fancy name for a vegetable garden located near a kitchen door, filled with tender greens, aromatic herbs, and select fruits that are harvested on a daily basis. Yet it can also be a way of life. A successful kitchen garden engages all of the senses through a rich tapestry of colors, fragrance, and ultimately, flavors. When you cultivate a kitchen garden, you actively engage with your source of food and integrate with your natural surroundings in a way that far surpasses the experience of purchasing food at the market. Growing your own food is truly the next logical step beyond local.

In 2009, when the Obama family planted a kitchen garden at the White House, it reignited a trend that had been largely dormant for the past century. The simple act of tilling up the lawn and sowing seeds inspired thousands of families to dig up their own backyards and plant vegetable gardens. This return to our agricultural roots resonated with what Thomas Jefferson once declared the noblest pursuit: farming. The Obamas set the stage for Americans to rediscover the simple pleasures of growing their own food as a welcome alternative to the high cost of packaged foods purchased in supermarkets.

Setting an example is one of the best ways we can effect positive change. When we bring our families together around the table to share our love for good homegrown food, we are cultivating a healthy choice that spreads beyond our own backyard. Teaching basic skills such as how to build a compost pile to keep waste out of landfills, how to encourage natural pollinators like honeybees, and how to cook with simple, whole foods harvested seasonally may seem like small steps, but when we learn to become responsible consumers, we also reclaim our health as a nation.

Next page