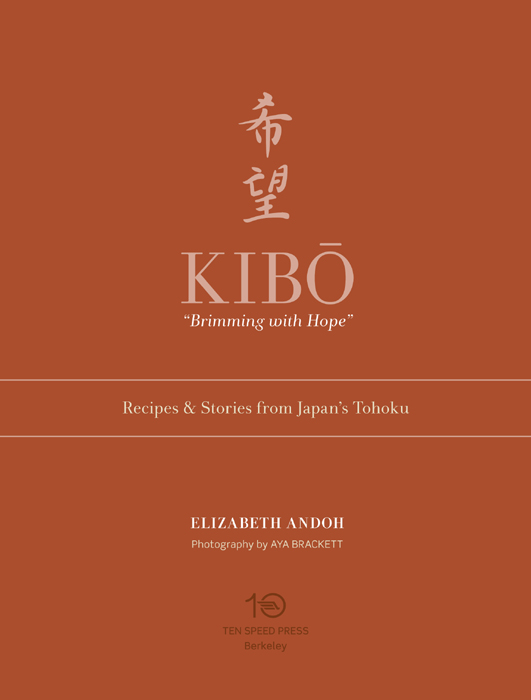

Text and some photos () copyright 2012 by Elizabeth Andoh

Photographs copyright 2012 by Aya Brackett

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

With the exception of text and photographs by Elizabeth Andoh and Aya Brackett, the following essays, additional photographs, and illustrations are reprinted by permission:

copyright 2012 by Yukari Sakamoto.

All rights reserved.

copyright 2012 by Jane Kitagawa.

All rights reserved.

copyright 2012 by Hiroko Sasaki.

All rights reserved.

Contents

= vegan/vegetarian

= vegan/vegetarian

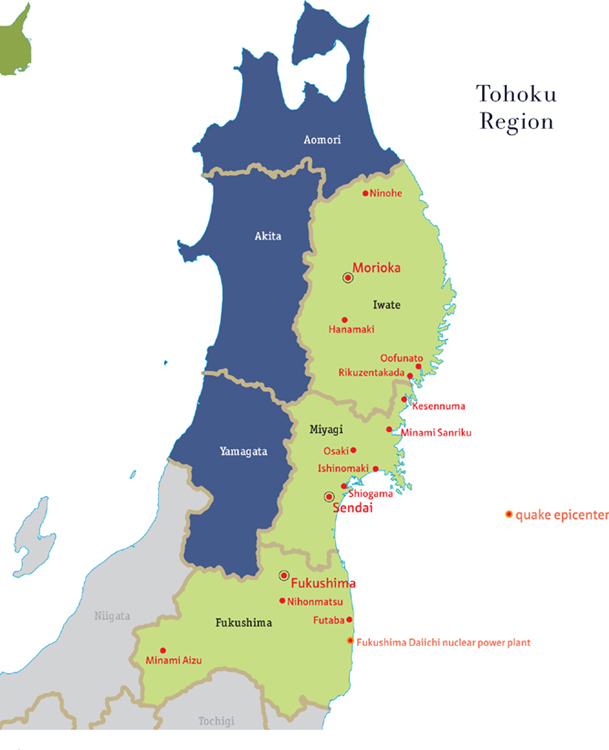

For detailed maps of each region, please refer to the section at the end of the book

WHATS IN A NAME?

Japans northeast is spoken of in various ways. Most common is the generic though geographically descriptive word: Tohoku. T means east and hoku means north.

The word sanriku (literally, three riku, or areas) is territorial terminology that encompasses riku , riku ch, and riku zen. In 1896 a large and destructive earthquake hit the region and media coverage at the time coined the phrase Sanriku to describe the larger area.

Michinoku, literally the remote road, refers to the northern territories and is cloaked in a romantic aura. It was made famous by the seventeenth-century poet Matsuo Bash in his travel-inspired verse, The Narrow Road to the Interior. The current spelling of Michinoku, using hiragana (syllabary symbols), no longer contains clues to the meaning contained in the original calligraphy, one of which is rikuthe same riku as appears in sanriku.

Introduction

The devastation of Japans regions began with an earthquake of remarkable force on Friday, March 11, 2011, at 2:46 in the afternoon. The record-breaking tidal waves (tsunami) that immediately followed left crushing, crippling destruction in their wake. In the days, weeks, and months thereafter, natures onslaught continued with hundreds of very strong aftershocks, many accompanied by yet more tsunami and by landslides. When winter thawed into spring, melting snow revealed deep, destructive fissures in the landscape. To compound the horror, damage to the Fukushima power plant produced severe and extensive energy shortages and wreaked radiation havoc, forcing widespread evacuation and focusing world attention on safety issues in the use of nuclear energy. The triple calamityearthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdownofficially has been named the Great Eastern-Japan Earthquake Disaster (Higashi Nihon Dai-Shinsai), shortened by most to a painfully simple word: Disaster (Shinsai).

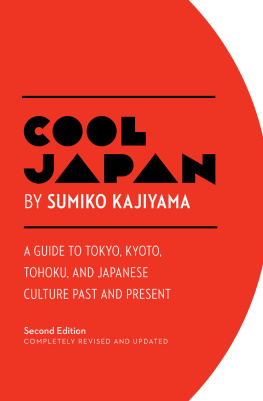

Yet, as Japan struggledcontinues to struggleto rebuild in the aftermath of tragedy, the prevailing mood is one of dogged determination, imbued with hope. In a single Japanese word: kib. And that is what I have chosen to name this culinary tribute to the Tohoku.

THE BIRTH OF THE KIB BOOK PROJECT

When the first huge, terrifying quake hit on Friday afternoon, March 11, I was in my Tokyo kitchen preparing for a cooking workshop the following day. Having lived through several large quakes before, including one in which I spent hours trapped in an elevator before being rescued, I went into automatic action trying to pretend it was just a drill, not the real thing. Trembling (me and the earth together), I shut off the stove and clambered my way to the front door. As I propped it opena precaution since frames can shift, jamming doors shutI witnessed a crane on the construction site across the street sway and totter. I donned my emergency-ready knapsack and crouched down in the doorway. The initial quake lasted for several minutesit seemed as though it would never stop.

Still trembling (me and the earth), I turned on the emergency news channel and learned the center of seismic activity (the largest on record in Japan, revised later that month to 9.0) was off the coast of . Gigantic tsunami (tidal waves) were predicted, and came and kept coming, with hundreds of aftershocks. Transportation in Tokyo came to a halt, and communication services were widely disruptedfrustrating, frightening. And then, news of the nuclear accident in Fukushima

In the weeks that immediately followed the Disaster, it became increasingly clear that mass evacuations, necessitated by the nuclear accident, would create a diaspora: displaced communities and disrupted lives.

Like others in Japan who had been spared significant property damage or personal injury, I wondered how I could help. As volunteer groups sprang up everywhere to address emergency needs, I found myself thinking more about long-term recovery. I was especially concerned with the plight of the refugees who were being relocated to distant places. I wondered how a writer and teacher of Japans traditional culinary arts could assist those in the devastated Tohoku area. After much soul-searching, I resolved to chronicle the culinary heritage of the especially of the three prefectures that were hardest hit: Fukushima, Miyagi, and Iwatebefore traditional foods there morphed into unrecognizable fare, or disappeared entirely. By writing in English, I could engage a wide-reaching readership, introducing them to local flavors while providing the global community with a way to share in the regions aspirations and determination. Even further, I sought a publishing house that would join me in supporting Japans rebuilding and renewal efforts.

My stalwart agent, Lisa Ekus, helped me hone my proposal. In the stifling heat of the summer of 2011, with frequent and severe aftershocks still rocking the Tohoku and nuclear power plant closings throughout Japan leaving homes and businesses everywhere with little or no cooling, we submitted my proposal to Ten Speed Press.

They responded enthusiastically, and shared my philanthropic commitment! But they also challenged me to rethink the platform, time frame, and scope of what I had originally envisioned. There would be time later, they said, for a more exhaustive treatment of the subject. (They knew, all too well, from working with me on my previous books, Washoku and Kansha, that my manuscript would be information dense.) Instead, they urged me to write something much shorter, more timely: an e-original that could be published by March of 2012, the first anniversary of the Disaster. That meant delivering a complete manuscript in just a few months

= vegan/vegetarian

= vegan/vegetarian