Introduction

Back in 1995, just before my book Emotional Intelligence came out, I remember thinking that I would have succeeded if one day I happened to overhear two strangers talking, and one used the term emotional intelligence and the other knew what it meant. That would signal that the concept of emotional intelligence, or EI (the term I favor instead of the popularization EQ) had become a meme, a new idea that had entered the culture. Today EI has far exceeded that expectation, proving a powerful model for education in the form of social/emotional learning, and recognized as a fundamental ingredient of outstanding leadership, as well as an active agent in a fulfilling life.

When I wrote Emotional Intelligence I was harvesting a decade of then-new research on the brain and emotions. I used the concept of emotional intelligence as a framework to highlight a new field: affective neuroscience. Research on the brain and our emotional and social lives didn't stop when I finished the book; if anything, it has accelerated in recent years. I included updates on this research in my books Social Intelligence and Primal Leadership, as well as in a series of articles in the Harvard Business Review.

In this book I want to continue those updates, sharing with you some key findings that further inform our understanding of emotional intelligence and how to apply this skill set. This is not an exhaustive, technical review of scientific data this is a work in progress that focuses on actionable findings, on new insights you can use.

Ill cover the following topics:

The Big Question being asked, particularly in academic circles: Is there such an entity as emotional intelligence that differs from IQ?

The brains ethical radar

The neural dynamics of creativity

The brain circuitry for drive, persistence, and motivation

The brain states underlying optimal performance, and how to enhance them

The social brain: rapport, resonance, and interpersonal chemistry

Brain 2.0: our brain on the web

The varieties of empathy and key gender differences

The dark side: sociopathy at work

Neural lessons for coaching and enhancing emotional intelligence abilities

There are three dominant models of emotional intelligence, each associated with its own set of tests and measures. One comes from Peter Salovey and John Mayer, who first proposed the concept of emotional intelligence in their seminal 1990 article.

Emotional Intelligence Goleman Model

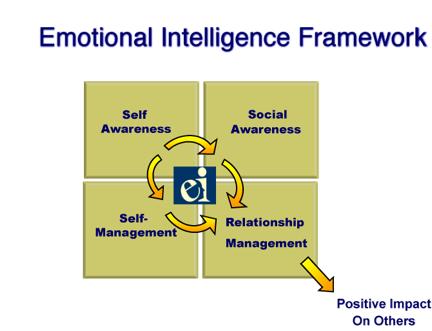

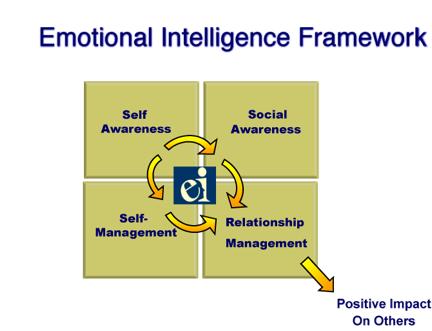

Most elements of every emotional intelligence model fit within these four generic domains: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management.

Is Emotional Intelligence a Distinct Set of Abilities?

This is the first big question: Is emotional intelligence distinct from IQ?

I first got an inkling that perhaps IQ alone did not explain all of career success during my freshman year in college. There was a guy down the hall from me in the dormitory who had perfect scores on his SATs, plus perfect scores on five advanced placement tests. From an academic point of view, he was brilliant. But he had a problem: zero motivation. He never got to class, he slept till noon, never finished his assignments. It took him eight years to get his bachelors and today he's self-employed as a consultant. Hes not a star performer, he's not the head of a big organization, he's not an outstanding leader. I now see he lacked some crucial emotional intelligence abilities, particularly self-mastery.

Howard Gardner, a friend from my days in grad school, opened up the conversation about different kinds of intelligence beyond IQ when he wrote about multiple intelligences in the 1980s. Howards argument was that for an intelligence to be recognized as a distinct set of capacities there has to be a unique underlying set of brain areas that govern and regulate that intelligence.

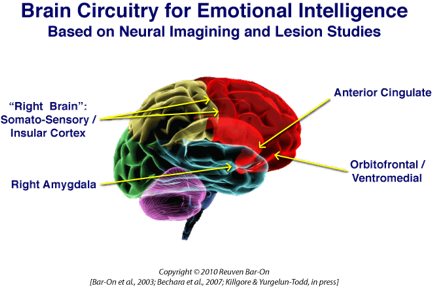

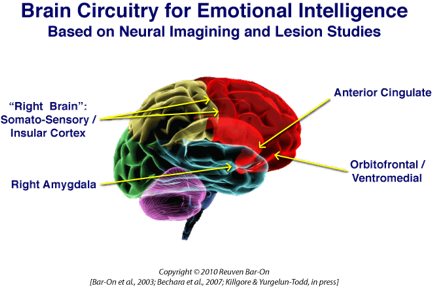

Now brain researchers have identified distinct circuitry for emotional intelligence in a landmark study by another old friend, Reuven Bar-on (by some unlikely coincidence, his mother was my fourth grade Sunday school teacher). Bar-On worked with one of todays outstanding brain research groups, headed by Antonio Damasio at the University of Iowa medical school. They used the gold standard method in neuropsychology for identifying the brain areas associated with specific behaviors and mental functions: lesion studies. That is, they studied patients who have brain injuries in clearly defined areas, correlating the site of the injury with the resulting specific diminished or lost capacities in the patient. On the basis of this tried-and-true methodology in neurology, Bar-on and his associates identified several brain areas crucial for the abilities of emotional and social intelligence.

The Bar-On study is one of the more convincing proofs that emotional intelligence resides in brain areas distinct from those for IQ. Other findings using different methods support the same conclusion. Taken together, this data tells us there are unique brain centers that govern emotional intelligence, which distinguishes this set of human skills from academic (that is, verbal, math, and spatial) intelligence or IQ, as these purely cognitive skills are known as well as from personality traits.

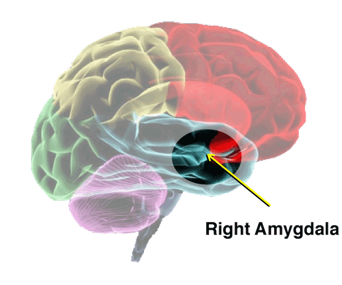

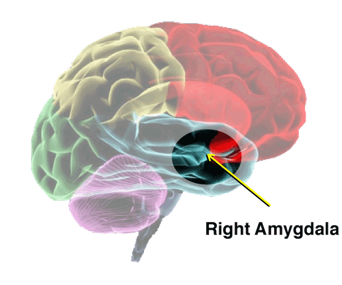

The right amygdala (we have two, one in each brain hemisphere) is a neural hub for emotion located in the midbrain. In Emotional Intelligence I wrote about Joseph LeDouxs landmark research on the role of the amygdala in our emotional reactions and memories. Patients with lesions or other injuries to the right amygdala, the Bar-On study found, showed a loss in emotional self-awareness the ability to be aware of and understand our own feelings.

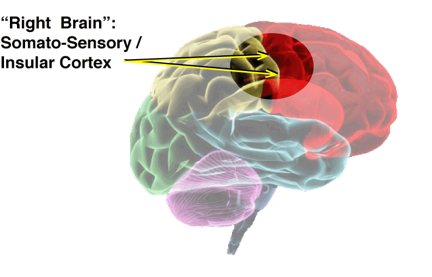

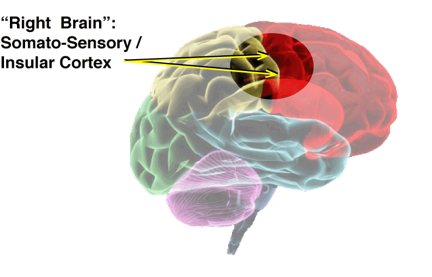

Another area crucial for emotional intelligence is also on the right side of the brain. Its the right somatosensory cortex; injury here also creates a deficiency in self-awareness, as well as in empathy awareness of emotions in other people. The ability to understand and feel our own emotions is critical for understanding and empathizing with the emotions of others. Empathy also depends on another structure in the right hemisphere, the insula, a node for brain circuitry that senses our entire bodily state and tells us how we're feeling. Tuning in to how we're feeling ourselves plays a central role in how we sense and understand what someone else is feeling.

1st Edition

1st Edition