MEASUREMENTS AND CONVERSION TABLES Measurements in this book are given in volume as far as possible. Teaspoon, tablespoon and cup measurements should be level, not heaped, unless otherwise indicated. Australian readers please note that the standard Australian measuring spoon is larger than the UK or American spoon by 5 ml, so use only tablespoon when following the recipes. LIQUID CONVERSIONS

| Imperial | Metric | US cups |

|

| fl oz | 15 ml | 1 tablespoon |

| 1 fl 02 | 30 ml | 1/8 cup |

| 2 fl oz | 60 ml | cup |

| 4 fl oz | 125 ml | Cup |

| 5 fl oz ( pint) | 150 ml | 2/3 Cup |

| 6 fl oz | 175 ml | cup |

| 8 fl oz | 250 ml | 1 cup |

| 12 fl oz | 375 ml | 1 cups |

| 16 fl oz | 500 ml | 2 cups |

| Note: |

| 1 UK pint 4 20 fl oz |

| 1 US pint = 16 fl oz |

SOLID WEIGHT CONVERSIONS

| Imperial | Metric |

|

| oz | 15 g |

| 1 oz | 30g |

| 1 oz | 50 g |

| 2 oz | 60 g |

| 3 oz | 90 g |

| 3 oz | 100 g |

| 4 oz ( lb) | 125 g |

| 5 oz | 150 g |

| 6 oz | 185 g |

| 7 oz | 200 g |

| 8 oz ( lb) | 250 g |

| 9 oz | 280 g |

| 10 oz | 300 g |

| 16 oz (1 lb) | 500 g (0.5 kg) |

| 32 oz (2 lb) | 1 kg |

OVEN TEMPERATURES

| Heat | Fahrenheit | Centigrade/Celsius | British Gas Mark |

|

| Very cool | | |

| Cool or slow | 275-300 | 135-150 | 1-2 |

| Moderate | | | |

| Hot | | | |

| Very hot | | | |

Authenticity

and tradition Whether you're sweating out a spicy curry from India or Sri Lanka, delighting in flavorful grilled meats from Korea or Vietnam, or marveling at the intricate delicacy of a Japanese or Thai meal, Asian food-with its delightfully heady mix of flavors, smells and colors-has plenty to offer the dedicated foodie. Asian cuisine is so much more than just food-steeped as it is in social and cultural lore. The region's recipes and cooking methods have developed over many centuries and now, thanks to globalization and migration, Asia's time-honored cooking traditions and fabled dishes have made their way to all corners of the globe.

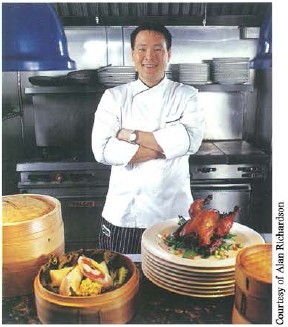

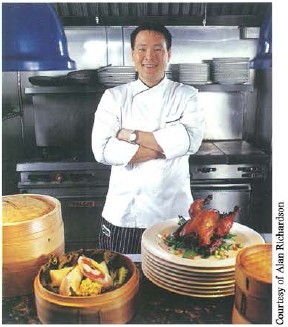

Asian ingredients that were once hard to come by are readily available in supermarkets worldwide as well as from Asian grocers and online merchants, and more people than ever before are eating Asian food on a regular basis. At my restaurant, Blue Ginger, and in my cookbook, I strive to properly blend the flavors of the East with those of the West. My feeling is that in order to successfully combine the two cuisines, one must first learn the proper and traditional methods of preparation for each region. The Food of Asia thoroughly and expertly presents the entire spectrum of the Asian culinary landscape, from Burma to Vietnam. For those who lack the time or rsources to travel to Asia, this book brings the region to you, all without leaving your own kitchen.  The weekly floating market at Ywama village, Inle Lake, is a colorful affair.

The weekly floating market at Ywama village, Inle Lake, is a colorful affair.  The weekly floating market at Ywama village, Inle Lake, is a colorful affair.

The weekly floating market at Ywama village, Inle Lake, is a colorful affair.

Burma, "The Land of Gold" of ancient Indian and Chinese manuscripts, has one of the Asia's least known cuisines. This is more a result of the country's long period of self-imposed isolation than the intrinsic quality of the food itself. However, as Burma-or Myanmar as it is now officially called-opens its doors to visitors and international business, more people are discovering its intriguingly different cuisine. The Land and its People Burma's beginning dates back some 2,500 years, when Tibeto-Burman-speaking people moved from Tibet and Yunnan into the northern part of the country. Kingdoms rose and fell over the centuries, many different tribes arrived and established themselves. The British gained control over the country little by little, annexing it to British India in stages, until the last king was dethroned in 1886.

Burma regained its independence in 1946, becoming a socialist republic in 1974. In 1979, the ruling authorities changed the name to Myanmar. Although religion and tribal customs influence the cuisine of the people of this polyglot land-in which today's specialists have identified 67 separate indigenous groups-it is perhaps the terrain and climate, which have had the greatest effect on regional cuisines. These factors determine the basic produce and therefore influence the dishes prepared by the people living in each area. The Burmese tend to classify their country into three broad areas: what used to be referred to as "Lower Burma," the humid Ayeyarwady delta around Yangon, and the land stretching far south into the Isthmus of Kra; "Middle Burma," the central zone around Mandalay, ringed by mountain ranges and thus the driest area in all of Southeast Asia, and "Upcountry," the mountainous regions which include the Shan Plateau and Shan Hills to the east, the Chin Hills to the west and the ranges frequented by the Kachin tribe to the far north. The long southern coastal strip of "Lower Burma," Tanintharyi, is washed by the waters of the Andaman Sea and shares a border with Thailand.

This region is rich in all kinds of seafood, which is understandably preferred to meat or poultry. While people in other areas of Myanmar eat freshwater fish caught in the rivers, lakes and irrigation canals, this coastal region offers a cornucopia of marine fish, crabs, squid, shrimps, lobsters, oysters, and shellfish. Flowing in a general north-south direction for some 1,349 miles, the life-giving Ayeyarwady rises in the mountains of the far north, then branches into a maze of rivers and creeks that make up the delta-about 168 miles at its widest. This is the rice granary of the nation. Rice is the staple crop in Myanmar and is consumed not only for the main meals of the day but for snacks as well. It is eaten boiled, steamed and parched; in the form of dough or noodles; drunk as wine or distilled as spirits.

A combined coastal length of about 1,492 miles and a network of rivers, irrigation channels and estuaries, particularly in the Ayeyarwady delta region, yields a dazzling array of fresh-and saltwater fish, lobsters, shrimps, shrimp, and crabs. The Ayeyarwady delta supplies the bulk of freshwater fish, sold fresh, dried, fermented or made into the all-important ngapi, a dried fish or shrimp paste (similar to Thai kapi, Malaysian belacan and Indonesian trassi). Mandalay, where the last king of Burma ruled, is the cultural heart of the fiercely hot, dry plains of central Myanmar. Irrigation has made it possible to expand agriculture from dry rice (which depended on seasonal rain for its growth) to include crops such as peanut, sorghum, sesame, corn and many types of bean and lentil. Various fermented bean or lentil sauces and pastes are used as seasonings in this region, rather than the fermented fish and shrimp products typical of the south. Not having access to fresh seafood, the people of the central plains generally eat freshwater fish, with the occasional dish of pork or beef.

Authenticity

Authenticity The weekly floating market at Ywama village, Inle Lake, is a colorful affair.

The weekly floating market at Ywama village, Inle Lake, is a colorful affair.