Myths are neither true nor untrue, but the product and process of mans yearning. As such, theyre the most primal thing bonding us to other people. Yet the phenomenon is much more than a snake feeding on its own tail. Myths gather momentum because they provide hope.

CYNTHIA BUCHANAN, COME HOME, JOHN WAYNE, AND SPEAK FOR US

Beyond the Promised Land:

Jews and Arabs on the Hard Road to a New Israel

Rivonias Children:

Three Families and the Cost of Conscience in White South Africa

Copyright 2013 by Glenn Frankel

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

For information address Bloomsbury USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Frankel, Glenn.

The searchers : the making of an American legend / Glenn Frankel.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN: 978-1-62040-064-7

1. Searchers (Motion picture) 2. Historical filmsUnited StatesHistory and

criticism. 3. Motion pictures and history. 4. Comanche IndiansTexasHistory19th

century. 5. MassacresTexasHistory19th century. 6. Indian captivitiesTexas.

I. Title.

PN1997.S3197F83 2013

791.43'72dc23

2012029453

First U.S. edition 2013

Electronic edition published in February 2013

www.bloomsbury.com

For Betsyellen Yeager

Everyday

Introduction

Pappy (Hollywood, 1954)

The most disastrous moment of John Fords illustrious Hollywood career took place at the U.S. Navy base on Midway Island in the Pacific Ocean in September 1954. The legendary film director was starting work on Mister Roberts, the movie version of the fabulously successful Broadway play, starring his old friend Henry Fonda. It should have been a great project: directing a comedy about Fords beloved Navy with one of his favorite stars, surrounded by his informal stock company of familiar supporting actors and film crew members, with a script by his trusted screenwriter, Frank S. Nugent. What could go wrong?

Almost everything, as it turned out. The biggest problem, surprisingly, was Fonda. Ford had gone to bat for him against the studio executives at Warner Brothers. They had wanted a younger, sexier, and more potent box office attraction like Marlon Brando or William Holden for the title role of Doug Roberts, a young Navy officer consigned to a backwater cargo ship during World War Two and desperate to see combat before the war ends. But Ford had insisted that Fonda, despite being forty-nine, owned the part after playing it to great acclaim for four years on Broadway, and even Jack Warner felt compelled to agree. Fonda was grateful; in a Dear Pappy letter he expressed his appreciation that he was working again with the complicated genius who had directed him in Young Mr. Lincoln, Drums Along the Mohawk, The Grapes of Wrath, My Darling Clementine, The Fugitive, and Fort Apache. that you are going to do the picture, Fonda gushed.

Nonetheless, from the moment they got to the location, the two men clashed. Fonda didnt like Nugents script, felt it was neither as funny nor as nuanced as the original play, and didnt care for the excessive physical comedy and coarse broad strokes of Fords direction. The Navy opened its gates to the film company: no one in uniform dared to say no to retired admiral John Ford, a decorated World War Two veteran. But on the first day of shooting at Midway, Fonda was disturbed by the way Ford rushed through the scenes and discomfited costar William Powell, who had trouble adjusting to Fords swift, one-take-and-lets-move-on pace. Ford, who dominated his film sets the way Louis XIV presided over the court at Versailles, could not help but notice Fondas worried expression.

At the end of the day, producer Leland Hayward arranged for a clear-the-air meeting in Fords room in the bachelor officers quarters. Ford was sprawled on a chaise longue with a tall drink in his hand. The conversation was short.

I understand youre not happy with the work, said Ford.

Fonda tried to be diplomatic. , Fonda began, and then went on to explain that the play had special meaning for him and Hayward. It has a purity that we dont like to see lost. And Im confessing that Im not happy with that first scene with Powell.

Ford had heard enough. Without warning, he sprang from the lounge chair, reared back, and punched Fonda in the face. The actor fell backwards, knocking over a pitcher of water, got up, and fled the room in stunned silence. Fifteen minutes later, Ford knocked on Fondas door and stumbled through a tearful, abject apology. Fonda says he accepted on the spot, but things after that were never the same. Ford was a lifelong alcoholic who prided himself on staying sober during a film shoot, but now he started grimly working his way through a case of chilled beer each day on the set. to go on, either Fonda or Ward Bond, another old Ford crony who had a minor role in the picture, finished up the days filming.

A few weeks later, soon after the film company returned to Hollywood, Ford was rushed to St. Vincents Hospital for emergency gall bladder surgery. Mervyn LeRoy took over and finished the picture. Mister Roberts was a box office hit, and won three Academy Awards, including Jack Lemmons first, for best supporting actor. But Ford and Fonda were both bitterly disappointed with the film and with each other. They never worked together again.

John Ford emerged from the Roberts debacle weakened physically and emotionally. He was sixty, a smoker and a drinker, and in poor health. and that they were terrible ones.

Still, Ford wasnt finished. As he tried to put back together the pieces of his damaged career following the humiliation of Mister Roberts, he turned to what he knew and loved best.

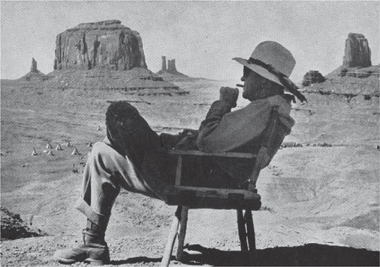

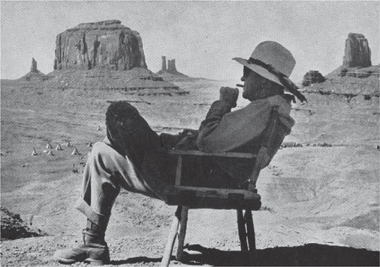

The Western had been John Fords favorite movie genre ever since he first arrived in Hollywood forty years earlier in the formative days of moving pictures, and he had made nearly fifty Westerns during the course of his career. There was something about a man riding a horse through the rugged landscape, Ford liked to say, that made it the most natural subject for a movie camera. He loved telling stories of cowboys and Indians and cavalrymen, and he loved taking his company of actors, cameramen, wranglers, and stuntmen on location to Monument Valley along the Utah-Arizona border, famous for its scenic beauty and its utter remoteness, far from the reach of the studio money men and their regiments of sycophantic retainers. There he would harangue and abuse his loyal crew, bend them to his will, and inspire them to do their finest work. And he loved working with John Wayne, his favorite actor and occasional whipping boy. Under Fords demanding and meticulous direction, Wayne had become Americas most iconic Western star: the solitary, taciturn man on horseback, true to his own code and adept with his fists and his guns. They were like father and son, wise old mentor and humble pupil, with Wayne in the subordinate role even after he became the countrys top box-office attraction.

Next page