To Rose Gray

contents

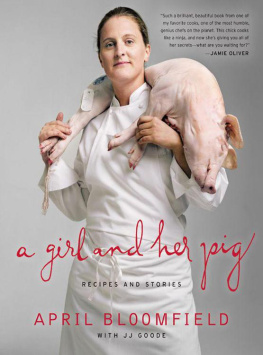

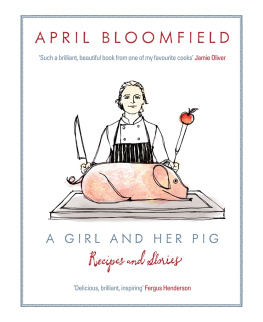

April Bloomfield hunches dejectedly over a bowl of meatballs, leaning a cheek on one hand. With the other, she pushes the meatballs around the bowl, eyeing them with great disappointment.

Were on the third floor of The Spotted Pig, her Greenwich Village restaurant, where weve spent more than a year working on this book. She cooks. I watch and ask questions, scribbling down notes or taking video. Today shes made lamb meatballs in a slightly soupy cumin-spiked tomato sauce. At the last minute, she added fresh mint to the pot, dolloped in thick, tangy Greek yogurt, and cracked in a few eggs to poach. When the meatballs were ready, she filled two bowls, passing one to me and keeping the other. I take my first bite and experience a sensation familiar to anyone who has eaten her food: eye-widening, expletive-inducing pleasure. The meatballs are stunning, a dish I thought I knew taken to a new level of deliciousness. Yet she sighs. Horrible, she says. These meatballs are horrible.

Spending time in Aprils kitchen is not typically a melancholy experience. Just the opposite, actually. When she starts cooking, all of her stressfrom a broken exhaust hood at The Breslin, the requisite food celebrities stopping in for lunch at The John Dory Oyster Bar, interviews with the media, which she dreadsevaporates, like wine in a hot pan.

As she preps, she looks as though theres nothing shed rather be doing than peeling shallots or chopping carrots. She practically ogles young onions and spring garlic. She inhales deeply over a pan of sizzling chicken livers, taking in one of her favorite aromas. Browning the lamb meatballs, shes utterly transfixed. Oh, that lovely color! she says. It makes me go all funny in the knickers. Theres always a song stuck in her head, and while she works, shell sing whatever it is in her Brummie brogue: a peek into the oven to check on a roasting lambs head, the flesh shrinking from its mandible, prompted snippets of the Lady Gaga song that goes, Show me your teeth. Whether shes turning an artichoke or filleting anchovies, its clear shes having fun.

Yet as the meatball episode demonstrates, April battles her own demons in the kitchen. She sets stratospherically high standards, standards so high that even she cant meet them. Her success and torment have a paradoxical relationship: her food is so good because she rarely thinks her food is good enough. When she is happy with the results of her labor, she often denies responsibility, assigning the deliciousness of, say, her roasted carrots to the carrots themselves for being so perfect and sweet. (Its a great tragedy, by the way, that a vegetable savant like April has become best known for burgers and offal. Ive never eaten more lovingly prepared vegetables than those from her kitchen.) And she barely eats what she cooks, instead assembling bites and plates for anyone nearby.

April does not impose her will from the kitchen; her lack of egotism leads her to empathize with the people who eat her food. When she composes dishes, she aims to re-create the little moments that bring her joy. Once, just before she whizzed stock and vegetables for a soup, I watched her fish out a slotted-spoonful of carrot chunks, then return them to the pot after blending. This way, she said, its like a little prize when you bite into one later. Isnt it lovely, she told me, when youre eating fried rice and you hit some egg? Ill search and search until I find another piece, for another hit of that fatty flavor. Of course, you dont want too much eggyou want to have to dig around for it. She cooks like someone who loves to eat.

Watching her reminds me why I love cooking itself, not just the food it produces, and inspires me to spend more time in my own kitchen. The essence of her food is simplicity. The luxe ingredients and ostentatious embellishments that define so much ambitious, big-city food are conspicuously absent. Instead, its unrelenting fastidiousness that defines Aprils food. A few fussy aspects of preparationobsessively trimming tomatoes of any pale flesh, making sure each sliver of sauting garlic turns golden brown, chilling radishes for saladlead to totally unfussy food. Her marinated peppers and Caesar salad, veal shank and chicken liver toasts are not deconstructed or creatively reimagined dishes. Theyre exactly what they promise to be, but they taste better than you ever imagined possible.

Like most cookbook readers, Im not a culinary school grad. Before working with April, I had never made aioli, let alone welcomed a lambs head into my oven. Yet now Ive served friends almost perfect clones of her cumin-spiked lentil puree, her bright-green pea soup punctuated with little chunks of ham and blobs of crme frache, and her veal kidneys tossed in garlic butter. Even my regular everyday cooking has improved since I succumbed to her infectious perfectionism, her attention to the little things. I splurge on salt-packed anchovies, as she does, because they make my food just taste that little bit better that pushes a dish from good to great. I use lemon to add brightness, not necessarily acidity, just as she does. I cut my carrots into oblique chunks so when theyre simmered, the edges will be soft but the center will retain its soft crunch and I wont miss out on the joy of chomping on one now and then.

One day, I decided to follow Aprils recipe for deviled eggs, and I brought them to The Spotted Pig for her to taste. I was terrified, anticipating a meatball moment. Instead, the famously finicky chef pronounced them quite good. She complimented me as if it were my recipe, as if I were responsible for how bracingly cold and vinegary they were. And, in some way, I suppose I was.

JJ Goode

When I was a girl, I wanted to be a policewoman. But then, when I was sixteen, I handed in my application too late. Its funny how a small thing like that can change everything.

I grew up in Birmingham, England, in a neighborhood called Druids Heath, which sounds like something out of Lord of the Rings . It was not that interesting, Im afraid. Birmingham is an industrial city, the second largest in England. It was a fine place to be a kid, though Id occasionally feel low about it. Everything there seems to be made of concrete. Its also full of housing estates, massive high-rise flats that are Englands version of low-income housing. Quite a few of my family members have lived in housing estates at one point or another, when they were struggling to afford rent. The buildings were all scary and cold and quite grim.

As a teenager, I got hooked on programs like Cagney & Lacey, CHiPS , and other cop shows. I know this sounds a bit nerdy, but I wanted to walk the beat, to work as part of a team. I liked rules and structure and repetition, the idea of doing something again and again until I was good at it. I even fantasized about wearing the uniform, although at the time, policewomen werent allowed to wear trousers: imagine chasing some villain while wearing a skirt.

Ill tell you, I wasnt the brightest bulb in the cupboard. I struggled through my work at senior school (like high school in the United States). I was always serious, and I never missed a day of studies. (I have the attendance awards to prove it.) Still, I preferred to put back pints with my mates at my local pub, staggering home late at night, my eyes squinty like two pissholes in the snow. And, like a prat, I missed my opportunity with the police academy and couldnt apply again for two years. I had to do something in the meantime. My mom sat me down. She suggested I consider becoming a florist. Just then, one of my sisters walked in wearing her cooking school uniform. I thought, I could wear that uniform. Why not have a go at cooking?

Next page