It is always for Jeff.

Remembering my momwe baked, we laughed, and we made cakes and memories.

Judith Weber, my friend and my agent, who watches over me and my work.

Bill LeBlond, my editorial director, and Amy Treadwell and Sarah Billingsley, my editors, who make my books happen in the best possible way.

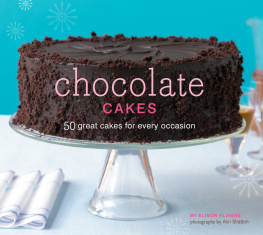

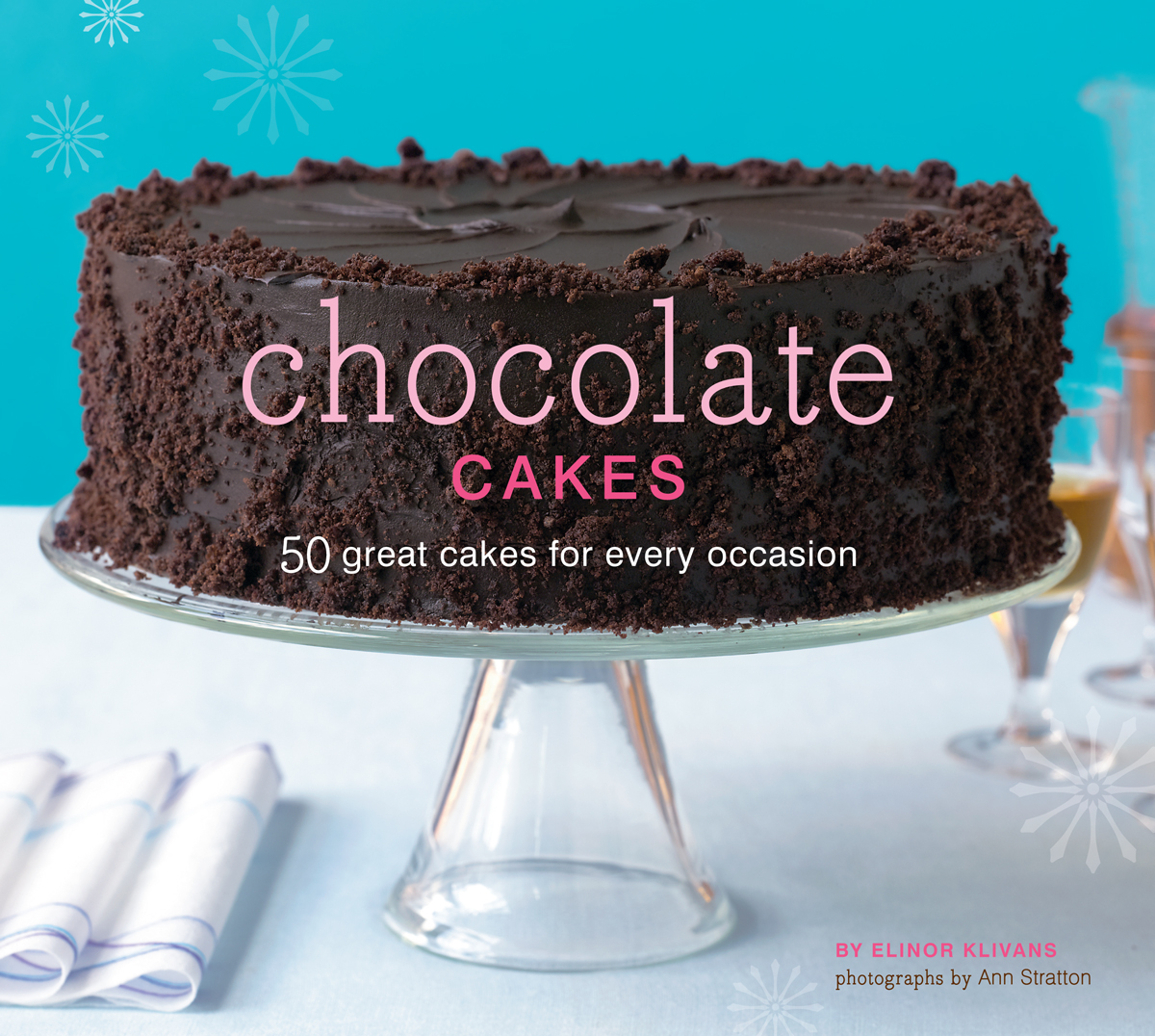

Ann Stratton, the photographer, Liz Duffy and Bette Blau, prop stylists who made and photographed my cakes in a way that made me want to make every one all over again.

A giant thank-you to Doug Ogan, Anne Donnard, Tera Killip, Peter Perez, and David Hawk, the brilliant publishing team at Chronicle Books.

Judith Dunham, my copyeditor, who also loved this book and helped make it better.

My family, Laura and Michael Williams and Kate Steinheimer and Peter Klivans; they bake, they taste, they support, they care.

My grandchildren, Charlie, Madison, Max, Sadie, Kip, and Oliver, who think their grandmother makes good cakes and who love to help her bake, decorate, and lick the spoons.

My father, who is proud of me and loves my books.

Thank you to the chocolate-cake testers who tested so many recipes so carefully: Jennifer Goldsmith, Katherine Henry, Cheryl Matevish, Melissa McDaniel, Rachel Ossakow, Dawn Ryan, Allyson Shames, Louise Shames, Kate Steinheimer, Laura Williams, and Charlie Williams.

A big thank-you to my circle of supporters and encouragers: Melanie Barnard, Flo Braker, Sue Chase, Rosalee and Chris Glass, Michael Drons, Susan Dunning, Maureen Egan, Carole and Woody Emanuel, Karen and Michael Good, Kat and Howard Grossman, Faith and David Hague, Helen and Reg Hall, Carolyn and Ted Hoffman, Kristine Kidd, Alice and Norman Klivans, Susan Lasky, Robert Laurence, Rosie Levitan, Gordon Paine, Joan and Graham Phaup, Janet and Alan Roberts, Pam and Stephen Ross, Louise and Erv Shames, Barbara and Max Steinheimer, Kathy Stiefel, Elaine and Wil Wolfson, and Jeffrey Young.

As I got to the end of testing recipes for this book, I was buried in chocolate cakes. My freezer was full. I had marched cakes up to the neighbors, served them to company, carried them on airplanes to family and friends, and brought them everywhere that I had been invited to for months. I sent out this e-mail to my friends:

Dear Friends,

I have too many chocolate cakes! So, I have decided to have a chocolate cake party.

I hope you all can come next Friday, September 5, at 7:30 p.m., to help me out and have a good chocolate time. House guests are welcome.

The replies were enthusiastic: Wonderful idea! What a great idea! We are so glad to help you out with your chocolate cake dilemma. Yummy! We will be there!

That same spirit continued right through the party as we feasted for hours on chocolate cake. When I looked at the table of cakes I had produced, even I was surprised at the variety. I had ice cream cakes, multilayer cakes, cupcakes, pudding cakes, big tube cakes, meringue cakes, cake rolls, deep-dish cakes, chiffon cakes, cheesecakes. It was the happiest party I had ever givenI knew chocolate cake would do that. It always does.

chocolate grows on trees

I havent found a place yet where the proverbial money grows on trees, but I found the next best thing that doeschocolate. About ten years ago, I had an opportunity to see the process of making chocolate, from harvesting the cocoa beans in a jungle plantation to manufacturing chocolate in a factory.

Out of the blue, a Venezuelan chocolate manufacturer called to invite me to travel with a small group to his country. We would visit the jungle where the cacao trees grow, then fly to the factory where the beans are turned into chocolate. This was extremely unusual because, after cocoa beans are dried, they are normally shipped to chocolate manufacturers around the world for processing. A trip like this was an opportunity that happens rarely to food writersat least to this one.

Four of us arrived in Caracas, where we boarded a small plane. Next, we traveled by four-wheel-drive vehicle over paved roads, then dirt roads, and then a dirt track, which led to the cocoa plantation. We walked through rows of cacao trees protected from the sun by the shade of tall, leafy trees. Although the cacao trees require a hot climate, they must be shaded from direct sunlight. I was surrounded by a jungle of chocolate. Granted, it was chocolate in its raw, unprocessed, cocoa pod state, but it was still a forest of chocolate-to-be.

Cacao trees require a hot tropical climate with abundant rainfall and thrive within 10 degrees latitude of the equator. Possessing these conditions, Venezuela has a long history of cocoa farming, as do other South American countries and various countries in Central America and Africa.

The cocoa pods themselves look downright comical, as they grow right out of the trunk or branch of the cacao tree. They resemble small elongated pumpkins that someone has glued to the trees. Although October to January and April to May are the peak harvest months, cocoa pods can be harvested year-round. The same tree at the same time of year can have cocoa blossom flowers and cocoa pods in all the shades of green, yellow, orange, and brown, the sequence that they go through to reach maturity.

The harvesting is a hands-on operation. After the cocoa pods are cut from the trees, they are brought to a central location on the plantation. One man quickly chops the end from each pod with a whack of his machete. He throws the open pods to workers nearby, who use a type of wooden spoon to scoop out the cocoa beans along with the sticky white pulp that surrounds them. One worker with a machete can keep four men busy scooping. The empty pods are thrown into a huge pile. They will be composted and later used to fertilize the cacao trees. Bees buzz around the sweet, sticky, pulp-covered beans. There is a sweet odor in the air, but not a hint of chocolate.

The beans are transferred indoors to bins to ferment for several days. The air in the fermenting rooms is thick and smells like that in a winery, but does not have the aroma of chocolate. During this process, the sticky white pulp dissolves, and the cocoa beans begin developing more complex flavors.

After fermenting, the beans are spread out on a large wooden platform to dry. If it rains, the entire platform can be rolled under cover to keep the beans dry. When dry, the beans look like large, elongated, dark brown coffee beans. Now they give off a faint odor of chocolate. After being sized and graded, the beans are shipped from the plantation to factories for processing into dark chocolate, milk chocolate, white chocolate, and cocoa powder.

Returning to Caracas, we went to the chocolate factory. There, the beans are cleaned to remove dirt, and any inferior beans are discarded. Next the beans are roasted, and at last the aroma of chocolate fills the air. Roasting cocoa beans is a carefully controlled process, during which many chemical changes take place that determine the final flavor of the chocolate. Once the beans are roasted, the shell is easy to crack, and the nibs or kernels can be removed. The shells are sent off to be used for fertilizer, garden mulch, or animal food; the nibs are processed into chocolate.

Traditionally, factories blended nibs from different plantations and cocoa bean varieties to produce various chocolate flavors. Recently, however, single-origin chocolates have become popular. Some chocolates are made from beans grown in the same region or even the same plantation.