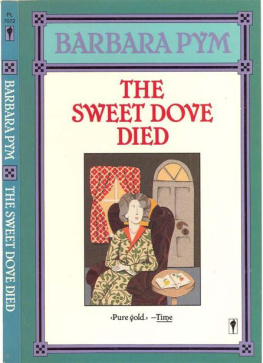

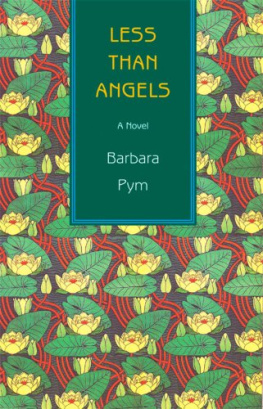

The Barbara Pym Cookbook

Hilary Pym & Honor Wyatt

INTRODUCTORY NOTE

THIS BOOK MAY NOT come as a surprise to readers of my sisters novels, who often comment on her many references to eating and food: carefully prepared meals (successful or unsuccessful), restaurant lunches, gourmet dishes, solitary suppers (actual or in prospect), Sunday family dinners, packed lunches and party food, teas of all kinds, breakfasts large and smallso that the question arises, Was she herself a good cook? Did she eat as well as some of her characters? I admit I never saw her prepare Sole Nantua, so memorable for Adam Prince in A Few Green Leaves, but I do remember an afternoon spent making ravioli (which Belinda in Some Tame Gazelle chose to make when she had the kitchen to herself), and the long, slow cooking of a cassoulet, of duck I think, when she decided that a tin of baked beans might have had exactly the same result. She enjoyed cooking in a creative way and liked to write down the menus we had when people came to eat with us, so I have been able to refer to these in compiling this book. I have also asked Honor Wyatt to collaborate with me in making the recipes, because as well as being a professional writer on the subject (I think her Crisis Cookery could still find a place in many households), she must have had an influence on Barbaras interest in cooking when we were sharing a house together in Bristol during the 1940s. The result is a combination, I hope, of practicalperhaps overfamiliar, for which I apologizerecipes for cooks, and useful references or reminders for Pym readers who are more interested in the idea and the associations of food than the actual preparation of it. But, as Wilf Bason says, what poetry there is in cooking!

HILARY PYM

A NOTE ON THE RECIPES

THERE ARE EQUIVALENTS and there are equivalents. In this book the equivalents between ounces and milliliters, pounds and grams, will work in your kitchen, not in the lab. Where precise amounts are important, as with baking, we have made every effort possible to ensure your success. The amounts of some ingredients or length of cooking time may vary according to altitude, oven temperature calibration, moisture content of flour, and the like. However, all of these recipes can be managed fairly easily.

In the British kitchen, tablespoons and teaspoons sometimes refer to somewhat larger utensils than are used in the United States. Standard measuring spoon measures are used in these recipes. So, a teaspoon has nothing to do with the item to the right of your dinner plate, but refers to the specific kitchen utensil so designated. You will run across a dessertspoon measure in some of the more traditional recipes. This standard British measure translates to 4 level teaspoons.

Liquid is sometimes measured in glass sizes and teacups in the British kitchen. As a guide, you can figure a teacup to be somewhat less than a cup, or about cup (225 ml). A wine glass measure also equals about cup (225 ml). A brandy glass of spirits measures roughly 23 tablespoons.

When baking you may be called upon to bake a pie shell blind, or prebake it. To do this, prepare your pastry, roll it out, line the pie tin, crimp the edges, and chill. To bake it blind, line the shell with foil or greaseproof paper, weight it with raw rice, beans, or pie weights, and bake at 400F (200C) for 10 minutes. Remove the weights and foil, prick the bottom of the shell with the tines of a fork, then return to the oven and bake for an additional 5 minutes to brown lightly. Set aside to cool, then proceed with your recipe.

Mixed spice, when called for, can include a selection of your favourite seasonings. A blend sometimes referred to as Spice Parisienne is recommended. Combine 1 tablespoon of cinnamon with 1 teaspoon each of ground cloves, ground ginger, and ground nutmeg. Use as needed.

Mixed herbs are even more a matter of taste. You can purchase one of the many mixtures commonly available at the market, or you can make up your own blend. A good basic mixture includes basil, thyme, oregano or marjoram, and savory. You are encouraged to experimentadd other herbs, adjust quantitiesaccording to your own preferences.

Several recipes call for cheese. In these cases, use a good cheddar, Gruyre, or Parmesan.

Starters and Soups

Ah! said George, as prawn cocktail was placed before us and white wine poured into one of the two glasses that stood at every place, and he began to eat purposefully.

An Academic Question

Prawn cocktails, smoked salmon, potted shrimps need no recipes here. But the first course might be a mousse.

SALMON OR TUNA MOUSSE

ounce (15 g) gelatin, softened in cup (75 ml) cold water

8-ounce (225 g) tin salmon or tuna or fresh salmon, cooked

cup (150 ml) light cream or evaporated milk

1 teaspoon lemon juice

2 tablespoons mayonnaise

1 cucumber, peeled and grated or chopped

Salt and pepper to taste

Stir in cup (225 ml) boiling water to softened gelatin and set aside. In a small bowl, flake fish with a fork, discarding skin, and set aside. Whip cream or milk until thick, then blend in lemon juice and mayonnaise. Add gelatin mixture, fish, and cucumber. Season well and mix thoroughly. Turn into an oiled 1-pint (600 ml) mold or small individual dishes. Chill about 4 hours until firm. Emma Howick in A Few Green Leaves decorated her tuna mousse with sliced cucumber of exquisite thinness.

It is an art all too seldom met with, Adam declared, the correct slicing of cucumber. In Victorian times there wasI believean implement or device for the purpose.

A Few Green Leaves

Emma had probably used the same recipe some months earlier for her ham mousse, which she had turned out on the same flowered dish.

With less effort than that required for the mousse, Emma could have made her ham into this simple version of the old-fashioned potted meat.

POTTED HAM

8 ounces (225 g) cooked ham, minced

Freshly ground black pepper to taste

Powdered mace to taste

Chopped parsley to taste

8 tablespoons clarified butter

Pound or mash together the ham, seasonings, and parsley. Pack tightly into little jars. Pour clarified butter over, cover, and refrigerate until ready to use. Serve with toast or rolls.

Rollo Gaunt, in An Academic Question, recalled a memorable asparagus mousse eaten in that delightful French restaurant, chez something or other.

ASPARAGUS MOUSSE

8 ounces (225 g) fresh green asparagus, trimmed

1 ounce (30 g) gelatin, softened in cup (75 ml) cold water, then added to cup (75 ml) hot chicken or vegetable stock

cup (150 ml) mayonnaise

cup (150 ml) double or heavy cream

Juice of lemon

Salt and pepper to taste

Cook the asparagus gently in boiling salted water until tender, then pure it, reserving some of the tips for garnishing. Combine pured asparagus with remaining ingredients and blend or whisk together. Place reserved asparagus tips decoratively in an oiled mold or individual dishes, spoon mousse over, cover, and refrigerate about 4 hours until set.

23 April. Philip Larkin to lunch. We had sherry and then the wine (burgundy) Bob gave me for Christmas (was this rather insensitive to Bob?). We ate kipper pt, then veal done with peppers and tomatoes, pommes Anna and celery & cheese (he didnt eat any Brie and we thought perhaps he only likes plain food). Hes shy but very responsive and jokey. Hilary took our photo together and he left about 3:30 in his large Rover car (pale tobacco brown).

Next page