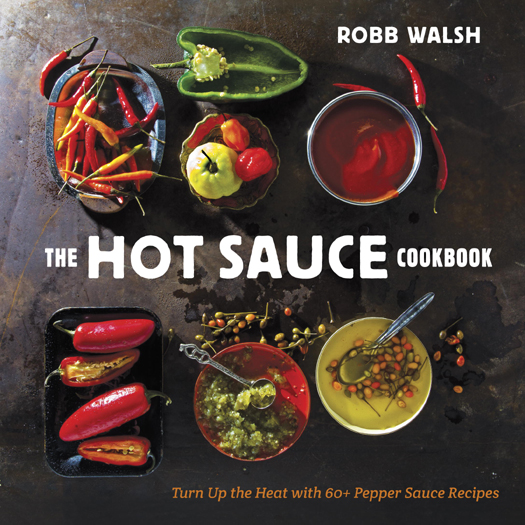

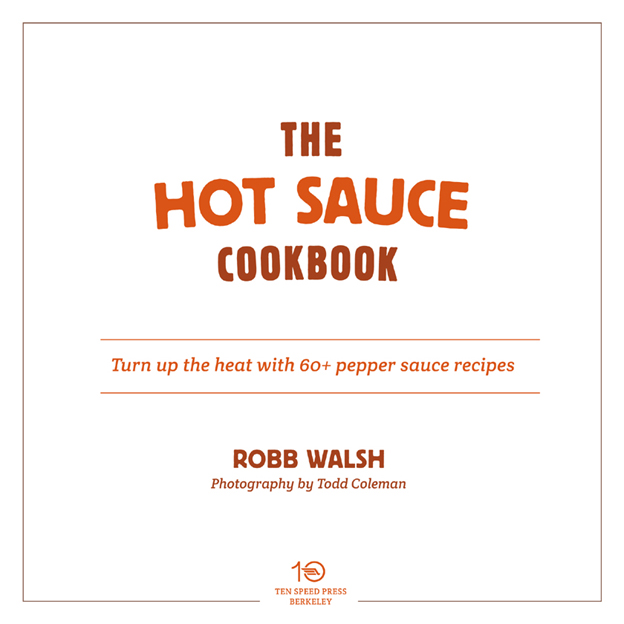

Copyright 2013 by Robb Walsh

Photographs copyright 2013 by Todd Coleman

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Clarkson Potter/Publishers and David Chang: The recipe from Momofuku by David Chang and Peter Meehan, copyright 2009 by David Chang and Peter Meehan. Adapted by permission of Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., and David Chang.

Zak Pelaccio: The recipe by Zak Pelaccio ( Food and Wine magazine, January 2006). Adapted by permission of Zak Pelaccio.

Ten Speed Press and Randy Clemens: The recipe Sriracha-Sesame Fruit Salad from The Sriracha Cookbook by Randy Clemens, copyright 2011 by Randy Clemens.

Adapted by permission of Ten Speed Press and the author.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 9781607744276

Hardcover ISBN: 9781607744269

v3.1

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

HURTS SO GOOD

CHAPTER 2

MESOAMERICAN CHILMOLES

CHAPTER 3

ISLAND HEAT

CHAPTER 4

LOUISIANA HOT SAUCES

CHAPTER 5

INTERNATIONAL PEPPER SAUCES

CHAPTER 6

CHILEHEAD CHEFS HOT SAUCES

INTRODUCTION

Chile peppers are totemic in many culturesthat now includes our own. In 1992, when sales of salsa surpassed ketchup, newspaper columnists, sociologists, and grocery industry gurus marked it as a major milestone, an indicator of irreversible changes in the ethnic makeup of our society. By 2002, the space allotted to hot sauces and salsas in the average supermarket went from a few feet of shelf space to close to an entire aisle. At the fast-food counter and the condiment station of the ballpark, hot sauce has joined ketchup and mustard in the plastic-squeeze-packet pantheon.

Business Week s list of the twenty-five top-selling condiments in America includes six salsas and four pepper sauces. The hot parade shows no sign of letting up. The 2012 Culinary Trend Mapping Report by food-industry think tank Packaged Facts declared that hot and spicy foods were still one of the fastest growing segments of the grocery business. The researchers reported that multicultural Generation Y and the growing Asian demographic were eager to try bigger, bolder, hot and spicy flavors in nearly every daypart, food and beverage category, and season.

From the mainstream American point of view, hot and spicy food seems like something thats arrived on the culinary scene in the last twenty years. But while some of the brand names might be new, the recipes for the hot sauces contained inside the bottles go back hundreds and, sometimes even thousands, of years.

This book is a casual tour of hot-sauce history, a practical guide for making it at home, and an exploration of the strange relationship between humankind and hot and spicy food.

In six chapters, we consider where hot sauce came from and where its going. well see how some of Americas top chefs are using hot sauces to raise the profile of fiery food in contemporary American cuisine.

CHAPTER 1

HURTS SO GOOD

Like coffee, tea, and marijuana, chile peppers are considered to be psychotropics. When you bite into a chile pepper, or eat a little hot sauce, the chemical capsaicin stimulates the salivary glands and the sweat glands and causes the brain to release endorphins, the natural painkillers that are stronger than morphine. Was it the mind-altering qualities of chile peppers that made them attractive to our cave-dwelling ancestors, or was it the zip they added to a boring diet? Or was it a little of both?

Whatever caused early man to love them, the chile pepper acquired mystical significance. The pods were used as currency in ancient Peru and appear in Incan stone carvings. In pre-Colombian Mesoamerica, peppers were prescribed for coughs, sore throats, and infections. The Spanish missionaries tried to ban them because they thought that chile peppers induced lust.

While English sailors were called limeys because they took citrus fruit juice to prevent scurvy, their counterparts on Spanish ships ate chile peppers for the same reason. Ounce for ounce, green chiles have twice as much vitamin C as oranges. They are also rich in vitamins A, C, and E, and packed with iron, magnesium, niacin, riboflavin, thiamin, and potassium. Capsaicin, which can be extracted from chiles, is also used to treat chronic pain.

The health-giving and flavorful ingredient was turned into all kinds of sauces and condiments. In those parts of the world where chile peppers grow year-round, it was the flavor and convenience of those sauces that made them appealing. But in parts of the world like North America, where the peppers are harvested in the late summer and hard to find for the rest of the year, making hot sauce was one of several methods of preservation.

Most North American chile peppers are descendants of the tiny chile pequn. Some ten thousand years ago, the wild chile spread to all of Central America, most of Mexico, and the tip of South Texas. The chile pequn was a tolerated weed, and its human cultivation was due more to benign neglect than active nurture. Its Latin name, Capsicum annuum var. aviculare says a lot about it. In Latin, annum means annual, and aviculare refers to birds. Like most of the wild peppers, chile pequn advertises itself to passing birds by growing erect from its stem and turning a bright shade of red when it is ripe. The digestive tract of the bird softens the seeds of the chile, and the excretion provides a rich fertilizer. And since birds usually defecate while perched on the branch of a tree, the seeds are planted in the shade where pepper plants prefer to grow.

Early human preference for one wild chile strain over another encouraged mutations that produced fatter chiles, or ones that grew larger by virtue of hanging pods rather than an upright ones since these were better hidden from the birds. And these mutations evolved into the many cultivars we eat today. The cultivars got local names that were different from place to place.

In the 1980s, the rise of Southwestern cuisine in the United States set off an explosion of interest in indigenous ingredients and chile peppers in particular. American chefs, gardeners, home cooks, food manufacturers, and cookbook writers clamored for reliable reference materials. But scientists had despaired of keeping the many strains of peppers straight.