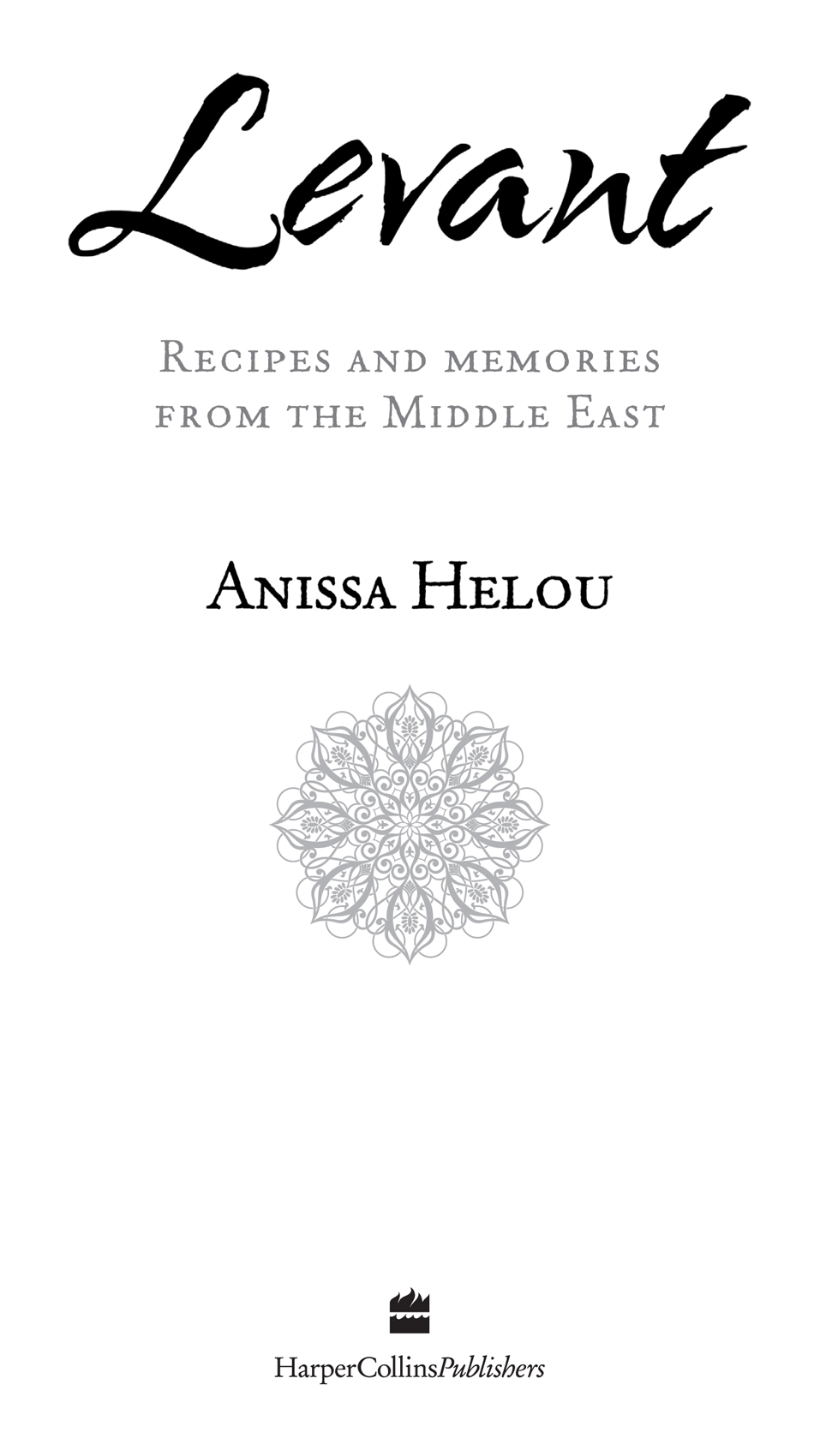

Contents

Lebanese Cuisine

Street Cafe Morocco

Mediterranean Street Food

The Fifth Quarter, an Offal Cookbook

Modern Mezze

Savory Baking from the Mediterranean

For my mother and late father, who taught me to love food.

Also for my late grandmother and Aunt Zahiyeh.

And for my siblings who were the first to share with me all those delicious dishes we grew up with.

First published in 2013 by HarperCollins

HarperCollinsPublishers

7785 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

FIRST EDITION

Text Anissa Helou 2013

Anissa Helou asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover photograph Jason Langley/Alamy

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN 9780007313433

Ebook Edition June 2013 ISBN: 9780007448623

Version 1

Australia

HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty. Ltd.

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street

Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

http://www.harpercollins.com.au/ebooks

Canada

HarperCollins Canada

2 Bloor Street East 20th Floor

Toronto, ON, M4W, 1A8, Canada

http://www.harpercollins.ca

New Zealand

HarperCollins Publishers (New Zealand) Limited

P.O. Box 1

Auckland, New Zealand

http://www.harpercollins.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

7785 Fulham Palace Road

London, W6 8JB, UK

http://www.harpercollins.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

10 East 53rd Street

New York, NY 10022

http://www.harpercollins.com

Soleil levant means rising sun in French and Levant the land to the east, where the sun rises is the word that came to describe the eastern Mediterranean at a time when the Mediterranean, which links three continents, Europe, Asia and Africa, was the centre of the world.

The term became current in the late sixteenth century with the creation of the English Levant Company that traded with the Ottoman Empire. A century later, the French set up the Companie du Levant for the same purpose and during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Levant became widely used by travellers in their accounts of the region, although not always referring to the same countries.

My Levant encompasses my own home countries, Lebanon and Syria, which were called the Levant States by the French when they had a mandate over them from 1920 to 1946 as a child, I spent the school year in Lebanon, in Beirut, and my summers in Mashta el-Helou in Syria. The term Levant for me also includes Turkey, Jordan, Palestine and northern Iran. Inclusion of the latter may be controversial, but Iranian cooking is the mother cuisine of the region. The Abbassid caliphs, who ruled from the eighth to the thirteenth centuries, favoured Persian cooks, and as their empire expanded, they took them along, which explains the sweeping influence of Persian cuisine over the cooking of the Middle East and North Africa. This, I think, gives me licence to include some of Irans classic northern dishes. The non-inclusion of Israel may be construed as controversial too, but as everyone knows, Israel is a very young state and many dishes that are now described as Israeli were originally, and still are, Palestinian, Lebanese or Egyptian, and I prefer to give the original rather than the assumed version of a dish where I can. Another country I could have included is Cyprus, which some historians and travel writers regard as part of the Levant. I have chosen not to include dishes from Cyprus in this book simply because this is a personal compilation of favourite recipes rather than a scholarly work, and as such I have made my own, very selective choice.

Most of the essential ingredients be they grains, pulses, nuts and spices or seasonal produce are common to the region as a whole. Many dishes are also shared between different countries, while just as many are specific to one country or another. Equally, when dishes are shared, there is enough of a difference in the way they are prepared to single them out as belonging to a particular country.

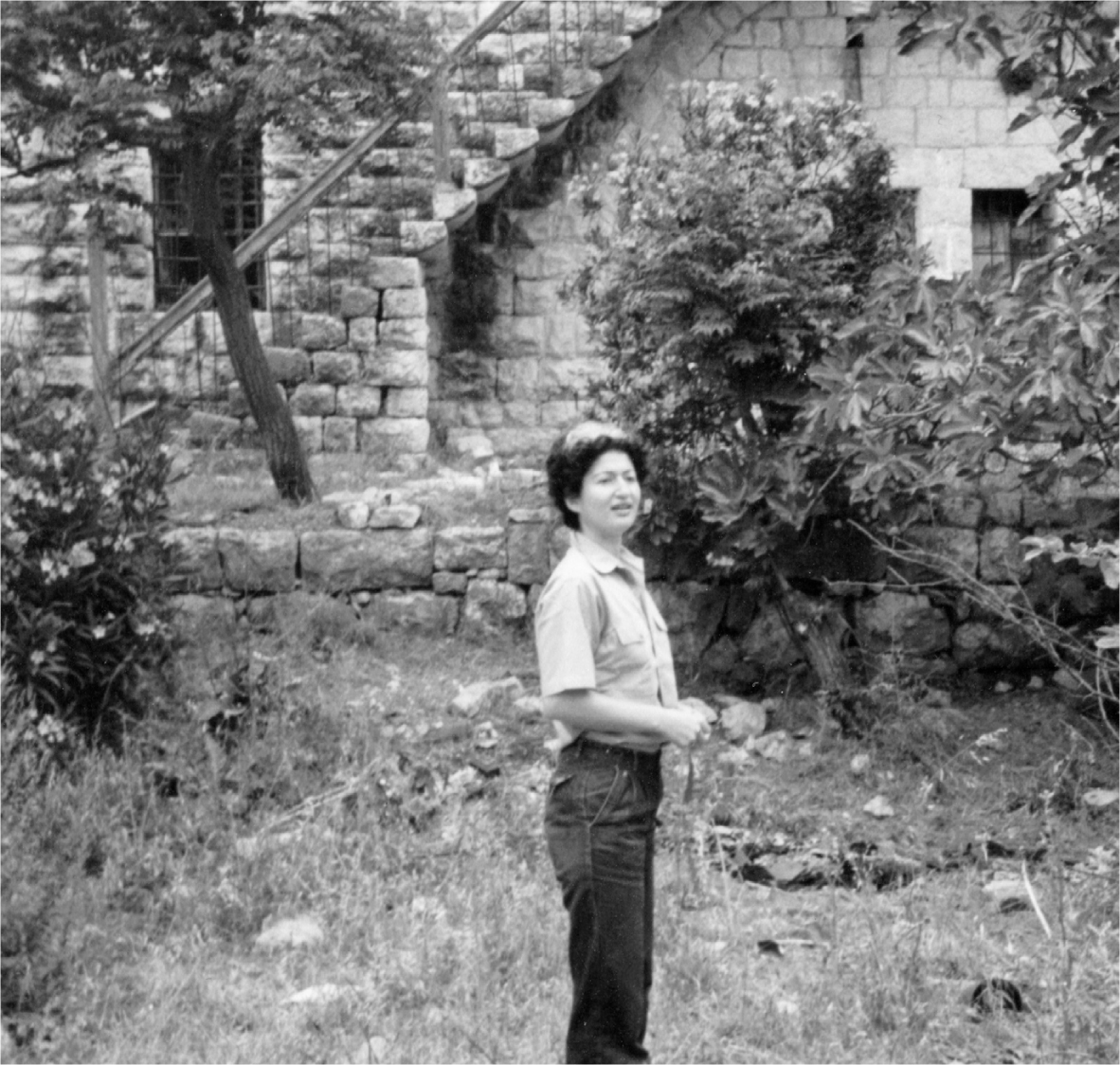

Anissa standing in front of one side of al-Dar in Mashta el-Helou, her fathers ancestral home in Syria.

Even the dominant flavours can be defined from one country to another. There are no combinations of sweet and savoury in Lebanon where the emphasis is on tart, fresh flavours. By contrast, complex or intriguing flavours are preferred in Turkey, northern Syria and Iran where dishes combine meat with fruit, and in some cases fruit juice, to create enticing sweet-savoury mixtures. Jordan and Palestine favour more subdued flavours and their dishes tend to be higher in fat, as do those from southern Syria. And Iran is the only region where rice is king, whereas burghul and frikeh (burnt green wheat that is dried and either cracked or left whole) are the staple elsewhere.

The main staple in the Levant is bread, an essential part of meals, but this too varies from one country to another. In Lebanon, a very thin, large pita is the most common type, used to scoop up food and to make wraps. Even though the country is tiny, there are regional variations, including marqq, a very large, paper-thin mountain bread baked over a saj (a kind of inverted wok), and mishtah, a flatbread from the south that is flavoured with spices and has added cracked wheat (jrish). Both are single-layered whereas further north you will find tabuneh, which is double-layered like pita but larger and thinner. Neither mishtah nor tabuneh tend to be found outside their region; indeed, I never knew them when I lived in Lebanon, discovering them only a few years ago when I was researching my book on savoury baking.

In Syria, the common bread, at least in rural areas, is tannur, a large, round single-layered loaf that takes its name from the tannur that was the original pit oven, built either below or above ground. Pita is common in cities and small towns where there are commercial bakeries. A few bakeries make marqq although the bread is not as common in Syria as it is in Lebanon. Jordan and Palestine have more or less the same type of bread, including shraak, which is like marqq, and tabn, which is similar to tannur but baked in a regular wood-fired oven. As for Turkey, the choice tends to be between pide, a long, oval, spongy flatbread, and lavash or yufka, a cross between marqq and tannur that is baked over a flat saj. Some regional Turkish bakeries offer a round flat loaf with deep indentations all over the top called trmakl ekmek, while many sell a fat, baguette-like bread that is used for sandwiches. Iran has three main types, all flat and each reserved for a specific meal.