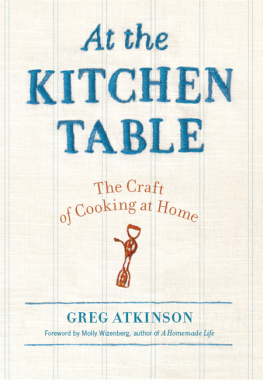

At the

KITCHEN

TABLE

At the

KITCHEN

TABLE

The Craft of Cooking at Home

GREG ATKINSON

Copyright 2011 by Greg Atkinson

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by Sasquatch Books

17 16 15 14 13 12 11 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Cover embroidery: Sarah Plein

Cover photograph: Rachelle Long

Cover design: Anna Goldstein

Interior design and composition: Sarah Plein

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN-13: 978-1-57061-734-8

ISBN-10: 1-57061-734-1

Sasquatch Books

119 South Main Street, Suite 400

Seattle, WA 98104

(206) 467-4300

www.sasquatchbooks.com

CONTENTS

H eres the thing: if he wanted to, Greg Atkinson could write a thoroughly chef-y book. He could write about fancy food from the fanciest of restaurant kitchens. Hes got the chops to. But hes also got his priorities in order. Though hes been a professional chef for most of his life, he has never lost sight of the place where most of our food, day in and day out, comes from: home kitchens.

I met Greg not all that long ago. He was moderating a panel at a Pike Place Market Foundation event, and I was a panelist. We had been charged with discussing the importance of eating local. (There are tougher jobs, no doubt.) So there we were, sitting around a table of name tags and Sharpies and stale blueberry muffins, introducing ourselves. I felt shy. I had heard Greg on the radio and had read his books and columns, and I asked him what he was working on. He told me about this book, the one youre holding right now. He said it was about home cooking, and then he said something that really struck me. He said it was about the idea that what feeds us is not only the food on the table, but even more, the experience, the feeling of sharing a table with the people we care about.

What I love about Gregs cooking, and his writing, is that its not about extravagant dishes or grand experiences. Its about everyday cooking and eatingalbeit, of course, very good everyday cooking and eating. Its about a way of living that we all have access to. Its picnics in the winter, homemade school lunches, a fish fry with coworkers. Simple food is the best food, he says, and reading his recipes, its difficult to argue. Ive bookmarked more than half of them.

Im tempted to say that Greg makes the ordinary feel extraordinary, because he does. But thats not quite it. I hope Im not putting words in his mouth, but what I think he would rather us feel is that theres nothing extraordinary about eating well and in good company. Its what makes us human. And its ours for the taking.

T his book is filled with the ghosts of people who shaped the world in which I learned to cook.

I am very grateful to those folks who came before me in both my own family and my wifes family, those who helped us appreciate the power of the kitchen table to serve as a focal point for family life. My grandmother, Sabra Quina Sanchez, and my mother, Annie LeClerc Sanchez Atkinson, were always guiding lights to me in the kitchen, as were my fathers grandmother, Myrtle Carter Atkinson, and his aunts, Lois Atkinson Geer and Mildred Atkinson Laney, who made amazing meals spring up out of hard ground in all sorts of times. And though he never cooked, my father has always had a deep appreciation for the ritual of the family meal, an appreciation that I inherited along with his love of words. My wifes family has also been an ever-increasing influence on my cooking, and more and more, I find myself cooking and writing to satisfy the tastes and sensibilities of the Lucas clan and the Latourette family.

The book is also filled with tangible evidence of a team of experts at Sasquatch Books who have helped it take shape: Gary Luke, the ever-patient publisher; Rachelle Long, the project editor who hammered my essays and recipes into a more readable form; and copy editor Erin Riggio, who makes it look as though I am far more detail-oriented than I really am.

Im grateful to the faculty and staff at Seattle Culinary Academy, who allowed me to work in their ranks for three years while the recipes for this book took shape. Im grateful to Kathleen Triesch-Saul and Kathy Andresevic at The Seattle Times, who have allowed me for years to formulate ideas for chapters in the form of essays and recipes for Pacific Northwest magazine. Im grateful for early readers of my drafts, including Sharon Ruzumna and Nancy Baggett, who provided helpful insight and good advice when some of the more difficult essays were taking shape. Special thanks go to Emily Young Ventura for testing the pasta recipes and giving me a nudge to jazz them up a little. Most of all I am grateful to my wife, Betsy Lucas Atkinson, and my sons, Henry Lucas Atkinson and William Erich Atkinson, who provide priceless, spontaneous critical evaluations of all my workboth written and cookedon a routine basis.

What does a chef do? He cooks. And cooking is a craft.

Cooking is repetition. And one must learn the craft.

THOMAS KELLER

W hen the arts and crafts movement was launched in the later years of the nineteenth century, it was as much about social reform as it was about design. In England, artists, illustrators, architects, and furniture designers like Walter Crane, John Ruskin, and William Morris, appalled by the industrialized uniformity and low quality of everyday objects, sought to replace the shoddy work that was coming out of factories with handcrafted objects. They believed that such objects would not only improve the quality of life for their users, but would also reinvigorate the crafts and provide meaningful work for artists and craftsmen. In America, craftsmen like Louis Comfort Tiffany, the architects Charles and Henry Greene, and furniture maker Gustav Stickley were motivated by similar ideals. Unfortunately, and somewhat ironically, the objects they produced were too expensive for most folks, and their efforts at egalitarian art became elitist.

At the time of the arts and crafts movement, mass-produced food was still in its infancy, and it probably didnt occur to anyone that the principles of the factory assembly line would eventually come to dominate food production the way they had the manufacture of furniture and decorative items in the home. But today, agribusiness in the form of multinational food giants is responsible for more than 90 percent of what we eat in the developed world. And in much the same way that cheap manufactured goods prompted the arts and crafts movement, the low quality and homogeny of our industrialized food supply has prompted farmers, chefs, and foragers to seek out traditional techniques and ingredients that offer an alternative to the processed grains, meats, and dairy products that constitute the vast majority of modern American foodstuffs. Just as artisans from our grandparents generation sought to create a better life for craftsmen while producing better goods for the home, food activists now hope to create a better life for farmers and chefs while providing better meals.