Ilhan Mehmed Lautliev (19252007).

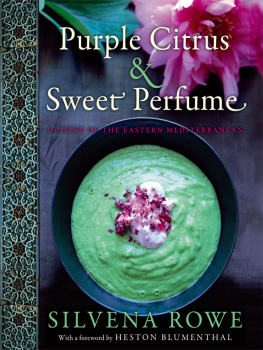

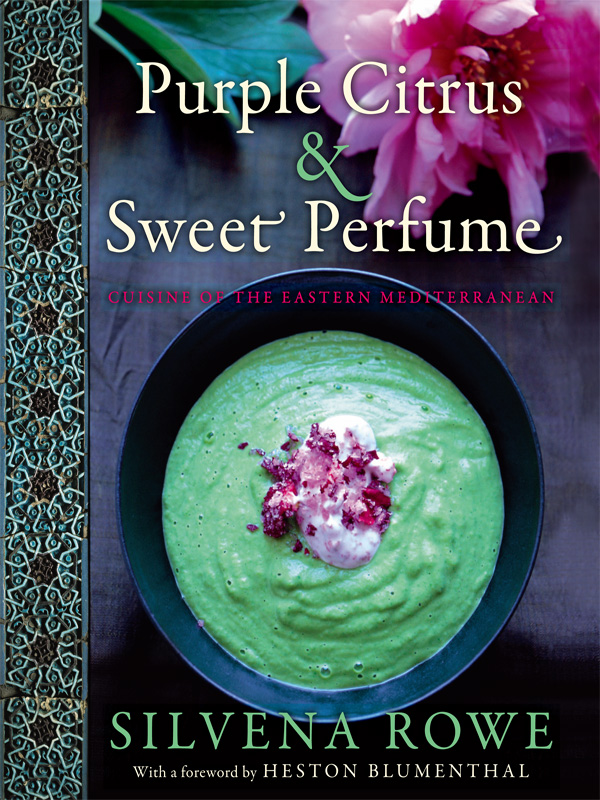

When Silvena asked me to write a foreword to her book, I couldnt help but say yes. Everything she does, be it writing, broadcasting or cooking, she approaches with the same boundless energy and enthusiasm, and her infectious passion is impossible to resist. She has written books and columns, presented television shows, been a consultant to top restaurants and cooked for an impressive lineup of celebrities, and each project is connected by her individual brand of dedication and her original take on food. As a chef, I find other peoples food memories fascinating, and Purple Citrus & Sweet Perfume is full of stories and reminiscences that set it apart from most cookbooks. Silvenas nostalgia for the aromas and flavors of her childhood really brings the recipes alive, and the book gives us a very personal glimpse at the relatively unexplored food cultures of these Eastern Mediterranean countries.

Her Eastern European heritage gives Silvena a unique perspective on this part of the world, particularly through her father and paternal grandmother, who were of Turkish descent, and it is fitting that she is our guide to the unfamiliar dishes, exotic spices and new ingredients of these cuisines. As well as the food of her childhood, there are more recent discoveries from the restaurants of Damascus and the cafs of Istanbul, and more traditional dishes from the kitchens of the Ottoman Empire. In fact, this stunning book is part travelogue, part memoir, part history lesson and part cookbook. It is beautifully written with a rich mix of evocative stories, poetry, fairy tales and history, woven into the carefully crafted recipes, and the fantastic photographs add to the seductive atmosphere captured by the words. Furthermore, the pages are so packed with Silvenas characteristic enthusiasm and irresistible passion, I defy anyone to resist.

In the early part of the twentieth century, when the latest medical breakthroughs were finding their way into the back streets of old Damascus, an elderly blind woman underwent a cataract operation, and afterwards, when she was recovering and the bandages were removed from her eyes, she was asked by the doctor what it was that she could see.

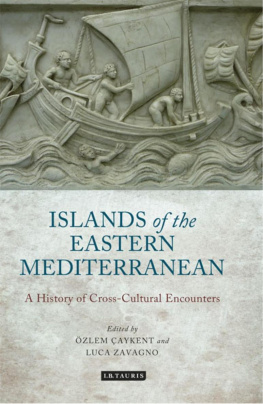

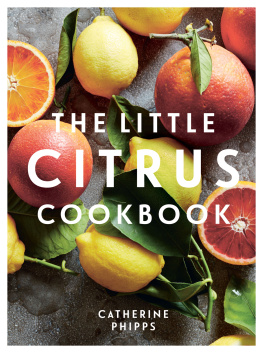

I can see your face, she replied. These plain and simple words serve to underline what I hope to achieve with this book. To open your eyes to the cuisines of the Eastern Mediterranean, to allow you to see and taste for yourself the wonderful panorama of fruits, vegetables, meat and rice dishes that this region has to offer; to wander through the kitchens of Turkey, Syria, Jordan and Lebanon, the cuisines of Europeans and Arabs, of Muslims, Christians and Jews, discovering as we go the old world of the Ottoman Empire. For 500 years the Ottomans ruled what is modern-day Bulgariawhere I grew upleaving only in the latter part of the nineteenth century. What followed was, in culinary terms, a black hole. At the very zenith of their power the Ottomans controlled not just the Eastern Mediterranean, but most of the Balkans, much of the Caucasus, the Crimea and the Middle East.

The cities of Athens, Budapest, Belgrade, Sarajevo, Bucharest, Sofia, Beirut, Damascus, Baghdad, Jerusalem, Mecca, Cairo, Alexandria, Tunis, everything to the very gates of Vienna, fell under the Sultans power. The Ottomans were no stick-in-the-mudsas their armies rolled through the neighboring countries they embraced the local cultures and, more important for this book, the local cuisines. The vast tracts of land over which they held sway offered unmatched fertility, and, just as the sun never set on the British Empire, so it is said that the fruits and vegetables of all seasons could be found in the markets of Constantinople (the Ottoman capital and now modern-day Istanbul), such was their all-encompassing power.  The entire region became a melting pot of cuisines, bringing a mlange of tastes, colors and smells. Chefs were invited (or enslaved) from across the Empire and beyond, and Armenian, Greek, Persian, Egyptian, Serbian, Hungarian and even French chefs came to Constantinople, first to the Sultans Topkapi Palace, then to the homes of the fabulously wealthy. Even the Spice Road, the most important factor in culinary history, was under the Sultans control.

The entire region became a melting pot of cuisines, bringing a mlange of tastes, colors and smells. Chefs were invited (or enslaved) from across the Empire and beyond, and Armenian, Greek, Persian, Egyptian, Serbian, Hungarian and even French chefs came to Constantinople, first to the Sultans Topkapi Palace, then to the homes of the fabulously wealthy. Even the Spice Road, the most important factor in culinary history, was under the Sultans control.

So only the best ingredients were allowed to be traded under the strict standards established by the courts, which meant recipes of unparalleled flavor could be produced. Consequently, a grand gastronomic tradition was developed by the aristocratic elite of the city, a culture that covered everythingthe ingredients, the methods of cooking, the kinds of food, the kitchens and even the table mannersand spread to the farthest regions of the Empire.  In its heyday the wealth and splendor of the Topkapi Palace were renowned across the world. The gardens, courtyards and vistas, the glittering domes and minarets, the baths and marble fountains, the carpets, textiles and ceramics, the paintings, the jewels, the objets dart. The swords, the hair plucked from the beard of the Prophet, the Holy Mantle and other relics of Muhammad brought from Mecca, the Meissen and Limoges porcelain presented by European royalty, the great fireplaces, the thrones, the Iznik tiles in all their brilliant colors. The sea-view windows encased with mother-of-pearl shutters.

In its heyday the wealth and splendor of the Topkapi Palace were renowned across the world. The gardens, courtyards and vistas, the glittering domes and minarets, the baths and marble fountains, the carpets, textiles and ceramics, the paintings, the jewels, the objets dart. The swords, the hair plucked from the beard of the Prophet, the Holy Mantle and other relics of Muhammad brought from Mecca, the Meissen and Limoges porcelain presented by European royalty, the great fireplaces, the thrones, the Iznik tiles in all their brilliant colors. The sea-view windows encased with mother-of-pearl shutters.

The Ottomans, open to all the sensory delights, were absolutely crazy about haute cuisine, and the vastness of their kitchens almost defies comprehension. Housed under ten domes, at their height the Topkapi kitchens employed 1,300 staff. Hundreds of cooks, specializing in different categories of dishessoups, pilafs, kebabs, vegetables, fish, breads, pastries, sweets, helva, syrups, jams and beveragesfed, on feast days and special celebrations, as many as 10,000 people a day. The Sultan had his own personal staff of seventeen specialty chefs and still more for his family. His food was prepared with great ceremony, and never consisted of fewer than twenty separate dishes. Each dish was brought in one at a time, covered and sealed with a ribbon to prevent it from being poisoned.

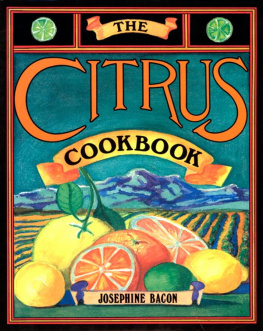

Following the example of the Palace, all the grand Ottoman houses boasted elaborate kitchens and competed in preparing feasts for each other as well as for the general public. In fact, in each neighborhood at least one household would open its doors to anyone who happened to stop by for dinner during the holy month of Ramadan, or during other festive occasions. So it was that the cuisine evolved and spread, even to the most modest corners of the Eastern Mediterranean. It would be impossible to cover every cuisine deriving from the Ottoman Empire, so I have stuck, with the odd sidetrack, to the eastern end of the Mediterranean. Here you will find a modern twist on the classic recipes of this rich culinary tradition, following in the footsteps of the great Ottoman chefs who combined the sweet and the sour, the fresh and the dried, honey and cinnamon, saffron and sumac, scented rose and orange flower waters with the most magical of spices.

In memory of the sweetest perfume, my father,

In memory of the sweetest perfume, my father,

The entire region became a melting pot of cuisines, bringing a mlange of tastes, colors and smells. Chefs were invited (or enslaved) from across the Empire and beyond, and Armenian, Greek, Persian, Egyptian, Serbian, Hungarian and even French chefs came to Constantinople, first to the Sultans Topkapi Palace, then to the homes of the fabulously wealthy. Even the Spice Road, the most important factor in culinary history, was under the Sultans control.

The entire region became a melting pot of cuisines, bringing a mlange of tastes, colors and smells. Chefs were invited (or enslaved) from across the Empire and beyond, and Armenian, Greek, Persian, Egyptian, Serbian, Hungarian and even French chefs came to Constantinople, first to the Sultans Topkapi Palace, then to the homes of the fabulously wealthy. Even the Spice Road, the most important factor in culinary history, was under the Sultans control. In its heyday the wealth and splendor of the Topkapi Palace were renowned across the world. The gardens, courtyards and vistas, the glittering domes and minarets, the baths and marble fountains, the carpets, textiles and ceramics, the paintings, the jewels, the objets dart. The swords, the hair plucked from the beard of the Prophet, the Holy Mantle and other relics of Muhammad brought from Mecca, the Meissen and Limoges porcelain presented by European royalty, the great fireplaces, the thrones, the Iznik tiles in all their brilliant colors. The sea-view windows encased with mother-of-pearl shutters.

In its heyday the wealth and splendor of the Topkapi Palace were renowned across the world. The gardens, courtyards and vistas, the glittering domes and minarets, the baths and marble fountains, the carpets, textiles and ceramics, the paintings, the jewels, the objets dart. The swords, the hair plucked from the beard of the Prophet, the Holy Mantle and other relics of Muhammad brought from Mecca, the Meissen and Limoges porcelain presented by European royalty, the great fireplaces, the thrones, the Iznik tiles in all their brilliant colors. The sea-view windows encased with mother-of-pearl shutters.