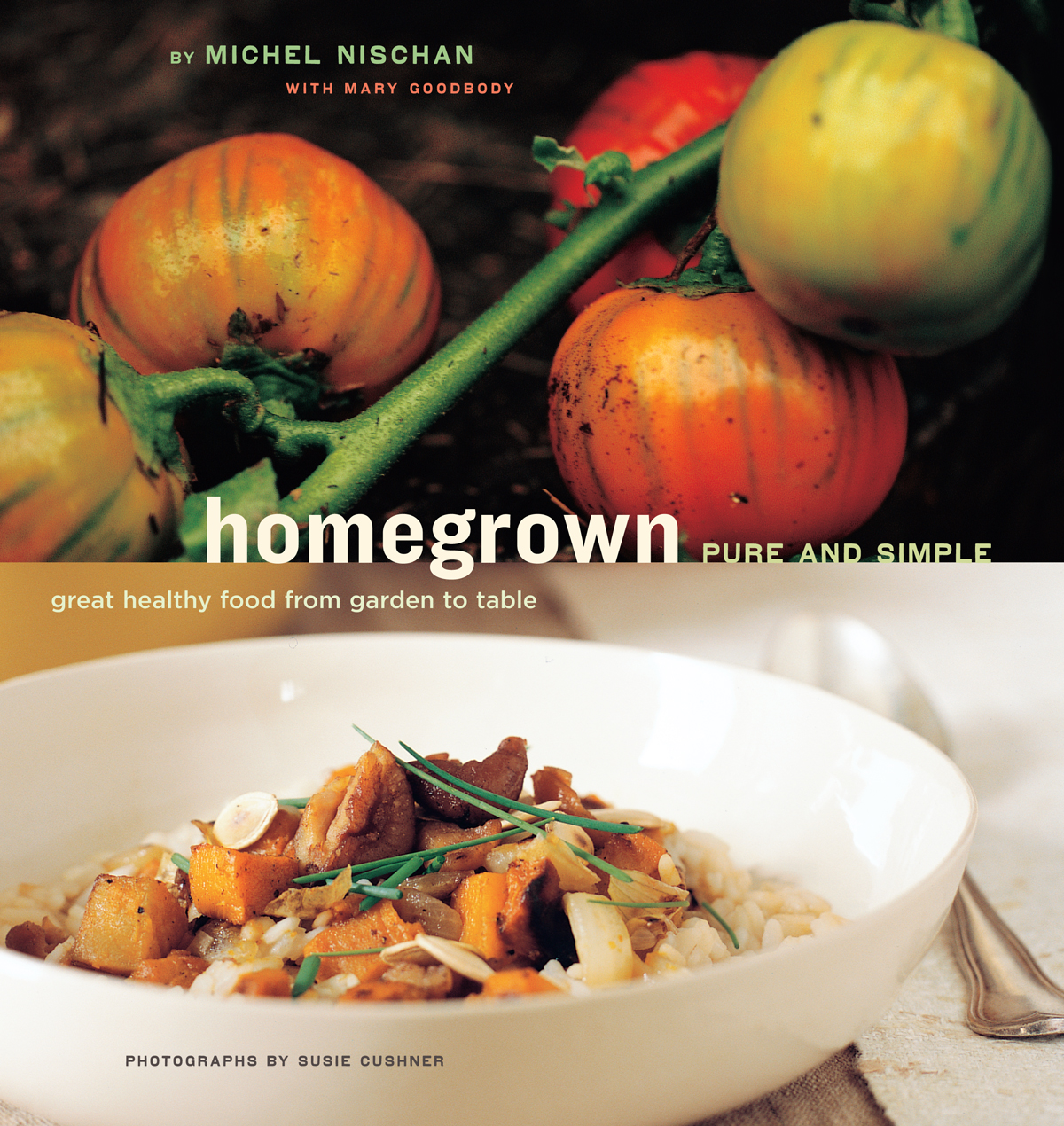

HOMAGE TO MY MOM

Feeling the love and a little bit of good ol country

IF SOMEONE HAD TOLD ME TEN YEARS AGO THAT ONE DAY I WOULD RETURN TO THE COUNTRY COOKING OF MY CHILDHOOD, I wouldnt have believed them. At the time, I had refocused my cooking on health and well-being and was extremely excited about my new direction. I thought I would never look back, but that is exactly what has happened. I am absorbed by memories of my mothers country cooking.

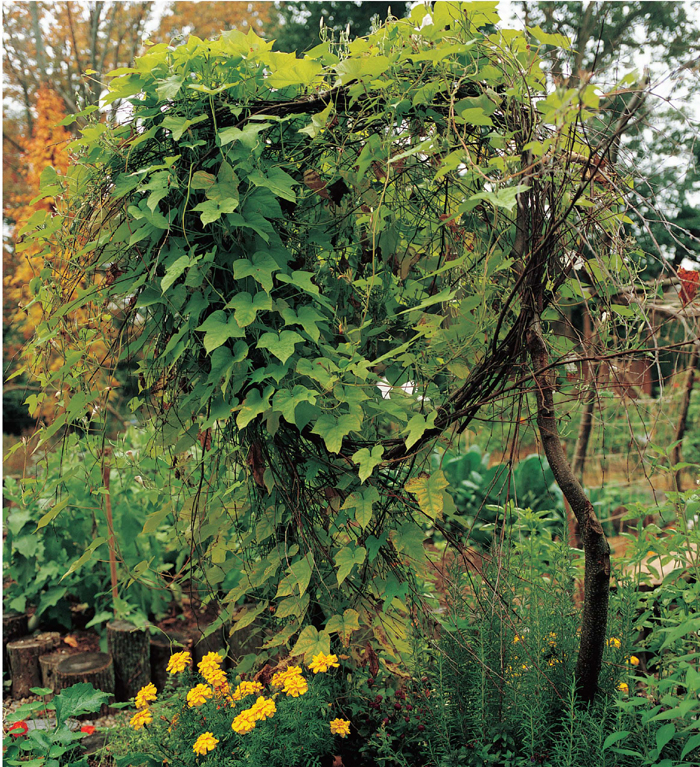

Like my mom, I have a large vegetable garden, and like my mom, I cook simple, healthful meals for my family. The difference is that she knew only Southern country cookingthe cooking of her childhood. As a professional chef with white-tablecloth training, I have learned a lot about various cultures and sophisticated cooking methods. I cooked my way around the world without ever leaving my kitchen. Yet something inside me kept pulling at me to return home. I have spent a decade silently struggling to reconcile my culinary heritage, which is down-home American country, with my desire to cook healthfully and to take good advantage of my excellent training. With this book, I have come to terms with all three elements.

You wont find recipes for fried chicken, ham and eggs, buttermilk biscuits, or coconut cake in these pages, but you will find homey dishes like . In the spirit of my first book, Taste: Pure and Simple, you will find an abundance of wholesome dishes for chicken, pork, beef, and fish. I pair these with farm-fresh vegetables and vibrant herbs and spices, so that the ingredients practically shout with pure, full-bodied flavor.

This book is all about my mother and the way she cooked. Its also about how she influenced me so that I found my path and became a chef. The life I have now is one I couldnt imagine when I was growing up in Des Plaines, Illinois. Then my universe was my family, my school, and my friends. Now my universe embraces all the wonders of the world. I am blessed with a loving wife and five children, I have traveled the country and much of the globe, I have worked in some of the best restaurant kitchens in New York City and elsewhere, and I count some of the finest people in the food business among my dearest friends. Through it all, I always come back to Mom.

MY MOTHER, MYSELF

My mother was robbed of her birthright to be a farmer. She was born into a farm family in Missouri with generations of farmers preceding her. Working the land was in her blood, but life and the industrialization of agriculture took her to suburban Illinois, where she and my father raised my brothers, my sister, and me in a small house with a backyard planted with vegetables right up to the sliding glass doors. It had not taken my mother long to decide that supermarkets were not for her when it came to fresh food for her family. She grew as many vegetables as she could in the backyard and fed us as she had been fed. What she couldnt grow, she bought at farm stands as far away from Des Plaines as Antioch, Illinois. In late spring, summer, and fall, we harvested fresh vegetables; in early spring and winter, we ate the canned, preserved, and frozen vegetables and fruits Mom had put up in the fall.

This is what I dream of doing for my growing family, too. With my new garden and with the commitment my wife, Lori, and I have to make it work for our kids and our lives, I know I will succeed.

While some chefs I know openly admit their mothers were not good cooks, many others insist they were magicians in the kitchen. I believe I have a leg up on the others because Mom was a farmer and a great cook, and anyone who doubts me is spouting blasphemy! All I have to do is prepare her recipes to convince even the most jaded critic. But is it healthful?

When I worked with the Association of Diabetes Educators on a recipe guide for Americans struggling with the daily challenges of diabetes, I submitted a recipe for smothered pork chops, cooked pretty much as my mother had cooked them. It came back from recipe testing with high marks, having met the dietary requirements for inclusion in the booklet. Why? Because the meat was served with plenty of fresh vegetables and the pork chops and serving amounts were smaller than in most contemporary recipes.

SUPPER-TABLE ECONOMICS

When Mom cooked smothered pork chops for us, the house filled up with tantalizing aromas that even wafted outside. We were starving by the time supper was on the table. Dad was the food cop. His rule was one pork chop per person until we tried a little of everything else: whole roasted cauliflower, collard greens, beans, home-canned tomatoes, and rice. We begged for a second chop. Heck, we thought we could eat a dozen chops! But in the end, those mighty tasty vegetables appeased our appetites.

Dad knew he was right. This was how he and Mom were raised growing up during the Depression. Meat was a luxury and never to be squandered. When we were young, money was tight for the family, and Dads policing of the supper table was a matter of economics, which also kept us healthy and fit.

In those days, most people exercised similar common sense when it came to feeding families. For one thing, more families still farmed or were close to farming roots. Convenience foods may have been making inroads, but the way Americans actually cooked in the 1950s and 1960s was pretty close to how they had cooked in earlier decades. Freezers were not as efficient, kitchens had no microwaves, and supermarkets didnt offer the staggering array of packaged, prepared foods they do now. Takeout was not a noun and a delivered pizza was still a novelty.

In two short generations, we find ourselves removed from farming and the concept that goes along with it, which is one of frugality amid abundance. It is a way of life that not only makes good sense but also promotes good health. My friend Terrol Dew Johnson from the Tohono Oodham Nation, in Arizona and New Mexico, tells me that the wisdom of his ancestors is contained in a single tepary bean. It signifies how a society learned through trial and error which agricultural practices worked and which did not. Mistakes literally cost lives and could not afford to be repeated.