All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including

photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publishers.

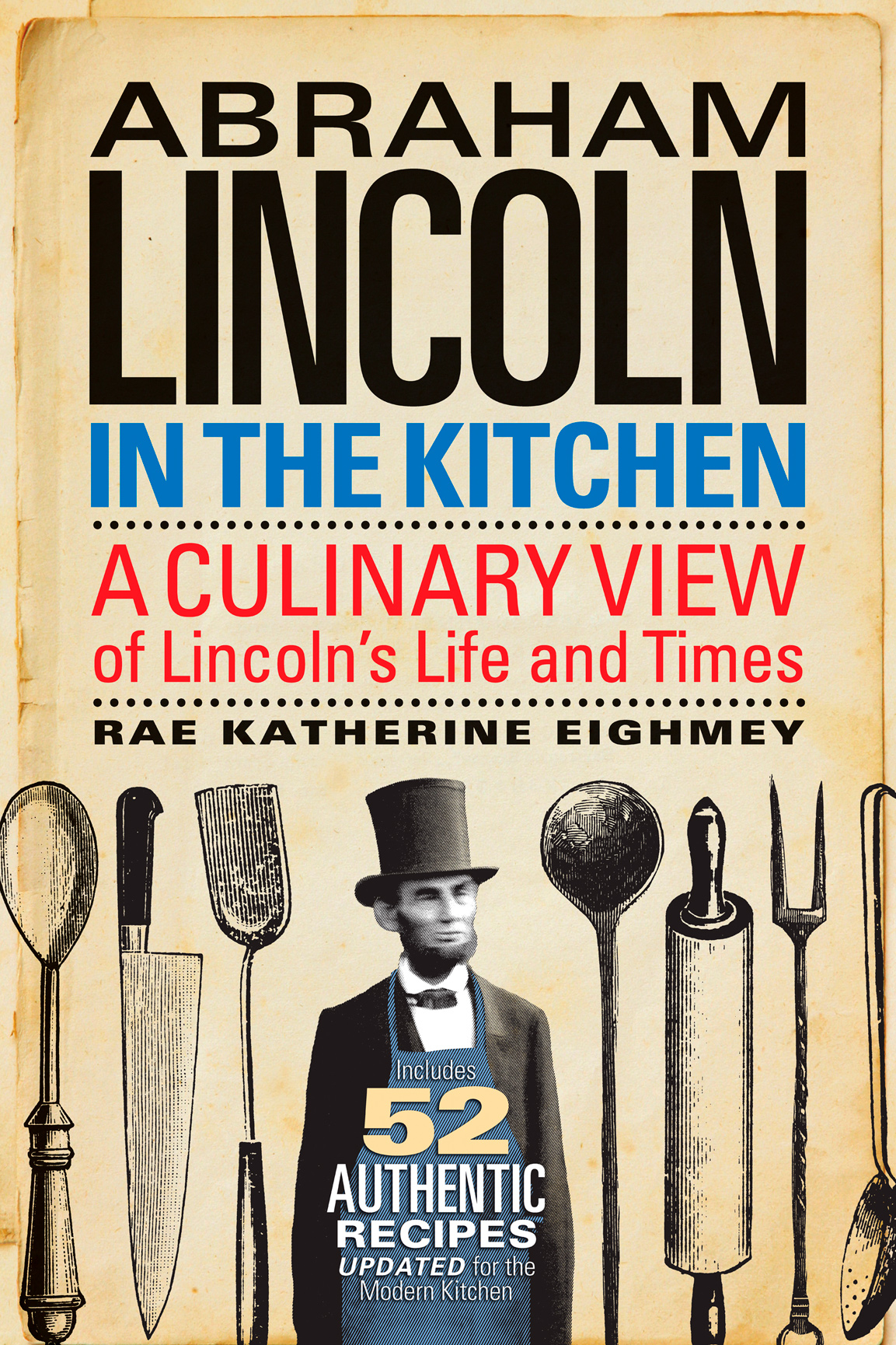

Eighmey, Rae Katherine.

Abraham Lincoln in the Kitchen : a culinary view of Lincolns

life and times / Rae Katherine Eighmey.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-58834-460-1

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-58834-455-7

1. Cooking, AmericanHistory19th century.

2. United StatesSocial life and customs19th century.

3. Lincoln, Abraham, 1809-1865.

4. PresidentsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

TX715.E3368 2013

641.5973dc23

In memory of F. C. E.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

Abraham and Mary Lincoln Corn Dodgers and Egg Corn Bread

CHAPTER 2

Lincolns Gingerbread Men

CHAPTER 3

Life on the Indiana Frontier Pawpaws, Honey, and Pumpkins

CHAPTER 4

Journeys of Discovery New Orleans Curry and New Salem Biscuits

CHAPTER 5

Bacon and Black Hawk

CHAPTER 6

Courtship and Cake The Lincolns Romance and Mary Todds Almond Cake

CHAPTER 7

Eating Up Illinois Politics Barbecue, Biscuits, and Burgoo

CHAPTER 8

Salt for Ice Cream Springfield Scenes from Diaries and Grocery Ledgers

CHAPTER 9

Piccalilli: Of Fruits and Vegetables

CHAPTER 10

Talking Turkey Clues to Life in the Springfield Home

CHAPTER 11

At the Crossroads of Progress Irish Stew, German Beef, and Oysters

CHAPTER 12

Inaugural Journey Banquets and Settling into the White House

CHAPTER 13

Summer Cottage, Soldiers Bread

CHAPTER 14

Cakes in Abraham Lincolns Name

INTRODUCTION

A braham Lincoln cooked!

The words leapt off the pages of my sixty-nine-year-old copy of Rufus Wilsons Lincoln among His Friends. I could hardly believe what I was reading.

Yet there it was. Phillip Wheelock Ayers, whose family lived three doors down from the Lincolns Springfield home at the corner of Eighth and Jackson, described how Abraham Lincoln walked the few blocks home from his Springfield law office, put on a blue apron, and helped Mary Lincoln make dinner for their boys. Other neighbors homey reminiscences told of Abraham shopping for groceries and milking the family cow stabled in the backyard barn with his horse, Old Bob. There must be more to this part of the Lincoln family story! The joyful prospect of research with books, pots, and pans immediately drew me in.

For me, food is the stuff of memory and of discovery. The cultural studies label is foodways, but I think the best word is cooking. And for the past two decades, cooking with century-old recipes, then eating meals made from them, has been my path for understanding and interpreting social trends and historical events.

Everyone has a favorite meal that brings forth a vivid memory or a dish that captures a moment in time: A taste of homemade peach ice cream immediately conjures up a summertime front porch. A holiday sweet-potato casserole Aunt Minnie always made brings memory of her to the table when she no longer comes. Sometimes the memory begins with food preparation. Just about every time I sit with a mixing bowl full of fresh green beans, I recall the blue-and-white bowl on my grandmothers lap as we sat in the screen porch snapping beans fortyno, fiftyyears ago. I can almost see and hear the rowdy Tobias boys next door running around to the side yard, their Boston bulldog chasing them as fast as its stocky legs could carry it, and the porch swing squeaking as my grandfather sat, reading the paper and waiting for dinner.

I also remember vividly the first antique recipe I made, and the delight that drew me into this area of study. I had been struggling to understand everyday life for the Jemison family in 1860s Tuscaloosa, Alabama. I was doing public relations and fund-raising for the restoration of their antebellum town home. The elegant Italianate structure had many stories to tellarchitecture, state-of-the-art engineering, political and Civil War historyall of it well documented. But I was searching to find a way to reach the lives of Robert Jemison, his wife, Priscilla, and their daughter, Cherokee. Then I found Mrs. Jemisons pencil-scrawled household notebook in the archives at the University of Alabama.

Mrs. Jemison had written down two recipes. The recipe for a jumble intrigued me. Ive baked and cooked since I was ten. It was obvious this was some kind of cookie, biscuit, or muffin. The mostly familiar ingredients were listed. Measurements were sketchy in the style common to mid-nineteenth-century cookbooks. There were no directions. Several days of research among the century-old cookbooks in the library stacks and dozens of test versions baked in my kitchen later, I had the perfect reconstruction of Mrs. Jemisons jumbles. One friend, whose family had Alabama roots five generations deep, gave me the highest compliment: They taste just like my great-grandmothers tea cookies.

My rediscovered jumbles were a crisp, not-too-sweet doughnut-shaped cookie. From them I was able to construct a life incident. I imagined Mrs. Jemison made a batch in the modern range she had in the basement kitchen and packed them in a tin for her husband to take with him as he rode off from Tuscaloosa to take his seat in the Congress of the Confederacy, meeting in Richmond.

Jumbles were just the beginning. Several other recipes had caught my attention as I carefully leafed through the fragile cookbook pages seeking jumble-like treats: cakes, breads, meats, vegetables. I began making some of them, too, just to see what they were like. They were wonderful! And I was hooked on this adventure of tasteful discovery. Now, thousands of recipes and five books later, I wondered: Could an expertise that began with the study of a family from the Confederacy ironically lead to an introspection of the man who dedicated his life to saving the Union? I began reading, thinking, and cooking.

The joy of studying history through cooking is that foods provide a complex sensory immersion into the past. This study, and the eating that follows it, is time travel at the dinner table and the only common experience that engages all the senses. An essay by food writer M. F. K. Fisher highlights the special power food memories have. In a 1969 book she recalled a dish of potato chips with lasting and real physical impact: I can taste-smell-hear-see and then feel between my teeth the potato chips I ate slowly one November afternoon in 1936 in the bar of Lausanne Palace. They were ineffable and I am still being nourished by them.