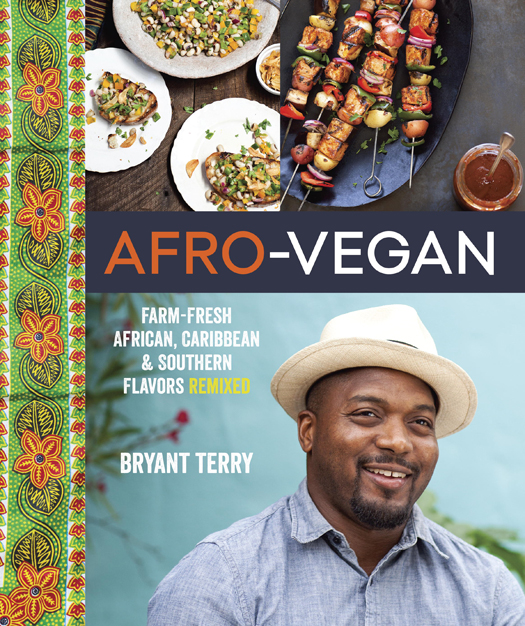

Copyright 2014 by Bryant Terry

Photographs 2014 by Paige Green

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC

All photographs by Paige Green with the exception of the following:

Photograph by Kristy May

Artwork courtesy Nick James

Photographs by Margo Moritz

Photograph by Frank Stewart

Photo-montage-on-wood pieces by Keba Konte

Photograph by John T. Hill

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Terry, Bryant, 1974

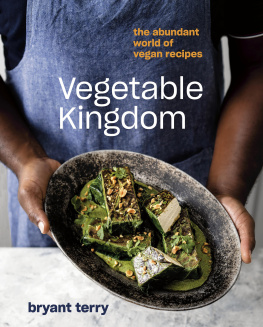

Afro-vegan / Bryant Terry. -- First Edition.

pages cm

Summary: A groundbreaking cookbook from beloved chef-activist Bryant Terry, drawing from African, Afro-Caribbean, and Southern food to create over 100 enticing vegan dishes--Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-1-60774-531-0 (hardback)

1. Vegan cooking . 2. African American cooking. 3. Cooking, American- -Southern style. 4. Cooking, African. 5. Cooking, Caribbean. I. Title.

TX837.T4337 2014

641.59296073dc23

2013048560

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-60774-531-0

eBook ISBN: 978-1-60774-532-7

Food styling by Karen Shinto

Prop styling by Dani Fisher

v3.1

Permission to Speak

BY JESSICA B. HARRIS

I smiled a lot as I read through the pages of Afro-Vegan , for in many ways it is a trip down memory lane. Reading it, I was taken back to the early days of my own work when I began to discover the culinary connections of the African Atlantic world as travel editor of Essence magazine in the 1970s. I recalled the first tastes of dishes sampled on the African continent that reminded me of those eaten in my grandmothers kitchens and the ingredients that I saw in markets, which were also in my mothers larder.

As I paged through the manuscript, reading the text for what has become this beautiful book, it became a journey of recollections, much like the one that I indulge in monthly in my online radio show. Faces passed through my minds eye. I recalled eating tagine de lgumes in a cadal tent in Marrakech, Morocco, and discovering that that countrys dada was in many ways the equivalent of the Souths mammys, a grand custodian of culinary traditions. I thought of my first Senegalese thiebou dienn and the connections it made to jollof rice, the Low Countrys red rice and even southern Louisianas jambalaya. I time-traveled to Brazil and the Caribbean and was transformed once again into the awkward young woman who spoke French and Spanish and Portuguese and liked to talk to old people in markets and taste what they had in their pots. My nostrils flared with the musty smell of old bookstores Id visited and dusty archives where Id researched. My mouth watered as I recalled the tastes of okra, black-eyed peas, and watermelon that were totems that marked the journey and all of the lessons learned. As I read Bryant Terrys proposed soundtracks, I heard the background music of my own journey: Maria Bethnia, Ornette Coleman, Zez Motta, Celia Cruz, Gilberto Gil, Bembeya Jazz, Youssou NDour were amplified and complemented by other newer, younger voices. As I read the names of writers and artists mentioned, I mentally poured rum on the ground for the repose of those friends who are gathered at the table in the sky, and I raised a glass high in tribute to all those who are still creating the universe in which I am honored to live. In all of his work, Bryant Terry shows that he is certainly one of those by his commitment and dedication. In Afro-Vegan , he amply and ably demonstrates that he knows that food and culture are inseparable and that history is always there on the plate.

Bryant Terry named this Permission to Speak, and I am delighted that he gave me the opportunity to so do. May his work continue to move us all closer, make us all healthier, and connect us all on the plate.

Introduction

Around the time I started writing this book, as a part of my research, I typed African-American beans into a search engine. I was expecting to view results about green beans, which often show up in traditional African-American cookery; red kidney beans, an emblematic legume of Louisiana Creole cuisine; and black-eyed peas, native to Africa and thought to bring prosperity throughout the year when eaten on New Years Day. Instead, the first search result was for Catfish in Black Bean Sauce , a film about Vietnamese siblings raised by African-American parents. The second result was for black (turtle) beans, and the next? Also black beans. Not one of the ten results on that page was about the variety of beans and legumes historically grown and eaten by African-Americans. In many ways, that comically sad moment on the Internet symbolizes the invisibility and marginalization of food from the African diaspora that was a major impetus for writing this book.

A large part of my mission in writing Afro-Vegan is to move Afro-diasporic food from the margins closer to the center of our collective culinary consciousness and to put its ingredients, cooking techniques, and flavor profiles into wider circulation. But there is more to the story than that. Because these riches have been hardearned, underacknowledged, and even exploited, using them wisely means coming to terms with the problematic narratives that surround them. There is a notable failure to (1) acknowledge that the modern world is indebted to ancient Africans for basic farming techniques and agricultural production methods; (2) appreciate the agricultural expertise (rice production), cooking techniques (roasting, deep-frying, steaming in leaves), and ingredients (black-eyed peas, okra, sesame, watermelon) that Africans contributed to new world cuisine; and (3) recognize the centrality of African-diasporic people in helping define the tastes, ingredients, and classic dishes of the original modern global fusion cuisineSouthern food. You see, it is not enough to celebrate the food of the African diaspora without appreciating the people who gave birth to this rich culinary heritage.

More than anyone else, people of African descent should honor, cultivate, and consume food from the African diaspora. Afro-diasporic foodways (that is, the shape and development of food traditions) carry our history, memories, and stories. They connect us to our ancestors and bring the past into the present day. They also have the potential to save our lives. As Afro-diasporic people have strayed from our traditional foods and adopted a Western diet, our health has suffered. Combined with the economic, physical, and geographic barriers that make it difficult to access any type of fresh food in many communities, the health of these populations across the globe has been devastated. In the United States, where I live and work, African-Americans suffer from some of the highest rates of preventable diet-related illnesses, such as heart disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes. Many factors contribute to the increase in chronic illnesses affecting African-American communities, and I would argue that the disconnect from our historical foods is a significant contributing force. While we continue to work for food justicethe basic human right to fresh, safe, affordable, and culturally appropriate food in all communitieswe must also work to reclaim our ancestral knowledge and embrace our culinary roots.

![Bryant Terry - Black Food : Stories, Art, and Recipes from Across the African Diaspora [A Cookbook]](/uploads/posts/book/300359/thumbs/bryant-terry-black-food-stories-art-and.jpg)