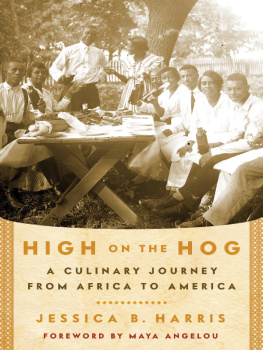

}IRON POTS AND WOODEN SPOONS

}175 AUTHENTIC CAJUN, CREOLE, AND CARIBBEAN DISHES }

BY JESSICA B. HARRIS

}

COPYRIGHT 1989

Ballantine Books }

Contents }

}

}Introduction } }Ingredients and Utensils } }Appetizers } }Soups } }Sauces and Condiments } }Vegetables and Salads } }Starches } }Main Dishes } }Desserts and Candies } }Beverages } | }next page } 1$ 20$ 37$ } }58$ } }75$ } }97$ } }118$ } }161$ } }178$ } |

}*WHEN CLICKING CTRL + F TO SEARCH FOR THE CHAPTER, INCLUDE THE $ SIGN AFTER THE PAGE NUMBER TO QUICKLY GO TO THAT PAGE.

}Introduction }

In my mind's eye there is a crescent, a sinuous imaginary line that begins on Mauritania's coast and sweeps downward along Africa's palm-fringed beaches from the buff-colored sand dunes of Senegal and Mauritania, through the lagoons of the Ivory Coast and beyond, to Togo, Benin, and Nigeria, then down to the forested regions of countries with names like drumbeats: Congo, Gabon, Angola. This same line continues to sweep across the Atlantic, carrying with it music, gesture, speech, dance, joie de vivre, and... yes, food.

On the other side of the Atlantic, it washes ashore on equally palm-fringed beaches that mirror those of the African littoral. These have names like Salvador da Bahia, Recife, and Sao Luiz. The curve moves lazily across South America through Ecuador and Colombia, where it meets other ancient cultures. It heads north to Guyane, Guyana, and Surinam and then begins a climb upward through the multicultural islands of the Caribbean. It jumps up to steel drum music in Trinidad while savoring roti; swings suggestively to the beguine while sipping a ti-punch in Guadeloupe. It speaks French, Spanish, Dutch, and English. It lingers for a while in the Creole areas of New Orleans, where the streets are perfumed with the aroma of pralines, and sets a spell in Charleston, where the words drip with molasses and magnolias. The cultural crescent finds rest in the barrios and neighbor-

}xi }

}IRON }POTS AND WOODEN SPOONS }

}hoods }of the rural South and the urban North in the homes of those of African descent. }

}This line is not static; it is mutabie a lifelinean umbilicus. Its flow has enriched the mother continent, Africa, and the New World. It is a conductor of people and of culture. It has brought to the New World Africa's rhythms, Africa's spirit, andperhaps most pervasivelyAfrica's food. }

}Some scholars argue that Africans first came into contact with the New World before Columbus. If so, Africa's influences on New World cooking go back over five hundred years. What is sure is that they go back almost to Columbus's arrival on these shores. In fact, the culinary histories of the New World and African cooking as it is today are so intermingled that it is almost impossible to separate them. Many Africans would argue that chile peppers, vital to much West African cooking, are indigenous to Africa, when in fact they had their origins in the New World. Watermelon, on the other hand, the quintessential American summer dessert, has its origins on the African continent, where it has been cultivated for many centuries. }

}The reciprocal flow of foodstuffs from the New World to Africa and back, along with the European influence on the West African diet, makes it virtually impossible to trace food trends with absolute accuracy. The African continent's cooking has changed radically, however, because of the foods introduced as a result of the voyages of discovery. From the mid-sixteenth to the end of the eighteenth century, the eating habits of Africa were transformed. The coconut tree arrived from South Asia at some time between 1520 and 1540; sweet potatoes and maize came from America in the same century. The seventeenth century saw the arrival of cassava and pineapple, while the eighteenth brought guavas and peanuts. All became so integrally a part of the African diet as to be truly African foods. }

}These changes make it impossible to trace yesterday's }

}X11I }

}Introduction }

}culinary influences using today's recipes. But looking at today's cooking in Africa and its counterparts in the New World, it is impossible not to be amazed at the similarity of methods of preparation, ingredients, and tastes. }

}It all started in Africa. Scholars have researched old Arab manuscripts and discovered some of the foodstuffs that were eaten by West Africans during the European Middle Ages. Reports of Arab travelers reveal that the African diet was somewhat similar to that of today. Grains played a major part in cooking. Ibn al-Faqih al-Hamadhani, the earliest known Arabic author to write about the foods of the West African peoples, emphasizes the role played by cultivated plants in the diets of people in the area that is now Mauritania and Mali. He mentions that they ate beans and a kind of millet known as dukhn. Other grains eaten by Africans during this period included some forms of sorghum, wheat, and rice. These grains were made into thick porridges, pancakes, fritters, bread, and various puddings served under a variety of sauces. Yams' (Dioscorea cayenensis and Dioscorea rotun-data), were also a major part of the local diet. The yam had an almost religious importance in many West African kingdoms. In ancient Mali, the execution of a criminal by beheading in a yam field was a central part of a ritual to ensure the fertility of the crops. Other ancient kingdoms also had yam festivals, and even today the harvesting of the yam crop is cause for celebration in parts of Ghana and Nigeria, and yam festivals are also held in the great Candomble houses of Bahia, Brazil. }

}Beans too formed a major part of the West African diet before European arrival. As early as 901 a.d., there are mentions of kidney beans and black-eyed peas. Broad beans, chick-peas, and lentils were also eaten. }

}All manner of green leafy vegetables were consumed, as were onions and garlic. Other foodstuffs included tur- }

}1. For a discussion of the naming }of }yams and yams vs. sweet potatoes, see page 97. }

}

}/KON POTS AND WOODEN SPOONS

nips, cabbage, pumpkins and gourds, and even cucumbers. The earth's bounty also extended to fruit, and during this period West Africans are known to have eaten watermelon, tamarind, ackee, plums, dates, figs, and pomegranates. Meats included beef, lamb, goat, camel, poultry, and varieties of game and fish.

Meat was usually boiled or roasted. When fresh meat was not available, dried, smoked, or salted meats or fish were substituted. These were usually combined with vegetables and cooked with shea butter (an African vegetable butter), sesame oil, or palm oil, the three main cooking oils of the area. Seasonings consisted of spices such as melegueta pepper or grains of paradise, ginger, and aromatic spices imported from North Africa. Salt was available but used sparingly. The resulting dish was usually served with a starch, which was dipped in the stew or sauce. Alternatively, the starch was served as a base on which the sauce was served. The whole was washed down with water either plain or sweetened with honey; milk either cow's, goat's, camel's, or sheep's, drunk either sweet (fresh) or sour; and for those in search of a buzz millet beer, mead, or palm wine.

European arrival in Africa altered the local diet. First came the Portuguese. The Portuguese are noted for their voyages of exploration. Most people lose sight of the immense role they played in transporting foodstuffs from one area of the globe to another. They are responsible for the transplanting to Africa of those tiny American incendiary chiles that characterize Thai and southern Indian cooking on the Asian land mass. They are also responsible for bringing corn, cassava, and white potatoes to West Africa. Chile peppers and tomatoes, two staples of modern West African cooking, were also transplanted from the New World.