The information contained in this book is based on the experience and research of the author. It is not intended as a substitute for consulting with your physician, allergist, or other health-care provider. Any attempt to diagnose and treat an illness should be done under the direction of a health-care professional. The publisher and author are not responsible for any adverse effects or consequences resulting from the use of any of the suggestions, preparations, or procedures discussed in this book.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Celestial Arts, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

Celestial Arts and the Celestial Arts colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

first learned about food allergies when I was six years old. The family that lived across the street had four children; the youngest was nicknamed Eggs. I didnt know who first called him Eggs; all I knew was that he couldnt eat eggs and that he was constantly itching his arms and legs, which were covered with thick, scary-looking skin that scabbed. I didnt know anybody else like that; in fact, I was actually more familiar with kids with polio. It wasnt until I was a third-year medical student working in pediatric dermatology that I saw a second person with food allergies. Three years later, when I worked in the Bronx during my residency, I saw more cases of food allergy, mostly in children rushed to the emergency room with hives or wheezing after eating a food they were allergic to.

first learned about food allergies when I was six years old. The family that lived across the street had four children; the youngest was nicknamed Eggs. I didnt know who first called him Eggs; all I knew was that he couldnt eat eggs and that he was constantly itching his arms and legs, which were covered with thick, scary-looking skin that scabbed. I didnt know anybody else like that; in fact, I was actually more familiar with kids with polio. It wasnt until I was a third-year medical student working in pediatric dermatology that I saw a second person with food allergies. Three years later, when I worked in the Bronx during my residency, I saw more cases of food allergy, mostly in children rushed to the emergency room with hives or wheezing after eating a food they were allergic to.

After moving to California, I seemed to see such cases even more frequently. During my first week of training in allergy and immunology at UCLA, I was asked to consult on an eleven-month-old boy from Arizona who weighed only ten pounds. He looked malnourished and had a rash around his mouth. My attending professor suspected child neglect or abuse, and we all expected him to thrive within days of being in the hospital. Time passed and he remained ill, with vomiting and diarrhea to boot. I checked up on him while a nurse was feeding him a cows milk-based formula from a sippy cup. He knocked the cup over and the formula poured onto his legs. Red blisters formed where the milk had spilled. At this point it became clear that he was allergic to the very milk with which we were trying to nourish him back to health. We stopped all forms of dairy and took him off all meds. Within forty-eight hours he was a different kidno vomiting, happier disposition, clearer skin, and increased appetite. He returned to the clinic two months later on no medications and was unrecognizable, weighing twenty-one pounds with no skin rashes.

These anecdotes show different manifestations of food allergy, and they illustrate how food allergy, once an esoteric condition, is becoming much more prevalent. The nation has seen a mysterious rise since the 1990s in the number of children with food allergies, now estimated to be three million, or one in every twenty-five children. In the past decade alone, the prevalence has increased by 18 percent. Being a busy allergist in the trenches, I diagnose five or more new food allergy cases each week.

So why are food allergies rising? Theres no good answer, but a lot of decent guesses. One theory is that we get exposed to nuts or other foods too early. I can remember well how some children with severe food allergies had mothers who ate large quantities of that same food while pregnant and while nursing. Could in utero exposure be the culprit?

For years, allergists have been recommending that allergenic foods be introduced to children at a later age to reduce the risk of allergy. However, a 2008 study of British children found that early exposure to peanuts actually lowered the risk of future peanut allergies.

Another theory explaining the increase in food allergies is that food in the United States is processed differently. For example, there is a much higher peanut allergy rate in the United States than in China; in the United States, peanuts are mostly dry roasted while in China they are mostly boiled, which decreases the amount of the allergenic protein in the peanut. Also, the processing of peanut butter in the United States involves whipping it to prevent the oil from layering out of the solid fraction; this spreads more of the peanut protein into the oil and may result in more peanut allergies. Another theory is that some people are actually allergic to the mold that grows in peanuts, and not the peanut itself.

There is also speculation that the increasing prevalence of food allergy is related to the increase in the amount of our food that is genetically engineered. One study examined a group of people who seemed to develop a new soy allergy even though they had previously tolerated soy products. It was discovered that the new allergy was only to soy that was genetically engineered from Brazil nut protein. Sure enough, all the affected people had severe Brazil nut allergy.

Whatever the reason, it is undeniable that the number of people with food allergies is on the steep rise. From a scientific point of view, allergies are the result of the body launching an exaggerated immune response against a particle it recognizes as foreign. We evolved this response to fight off infection, but the allergic immune system is so sensitive that it reacts to proteins in foods as though they were viruses. The body attempts to destroy the foreign protein by releasing histamine, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes. These chemicals are responsible for the symptoms of an allergic reaction. These symptoms, which usually occur almost immediately after exposure to the problematic food, can vary in intensity from a little itch on the tongue or skin to full-blown anaphylaxis, a swelling in the throat and lung airways that may be life-threatening. Allergies can also present with hives, a total body rash, vomiting, diarrhea, shortness of breath, wheezing, and shock, with a severe drop in blood pressure, loss of consciousness, a lack of air exchange, and ultimately, a heart arrhythmia.

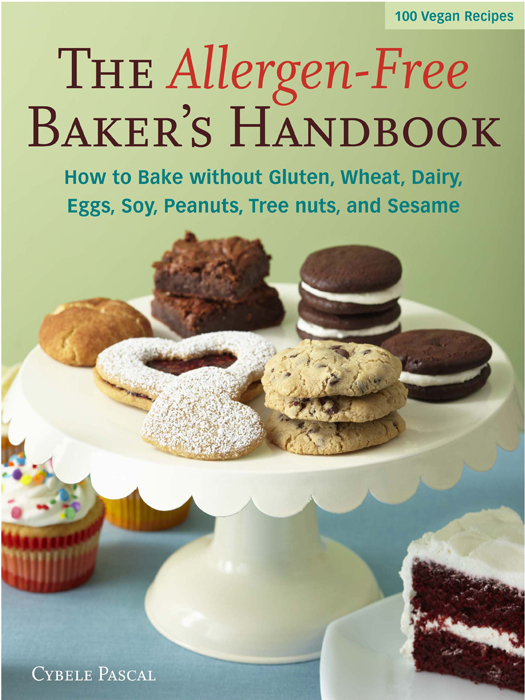

Although everyone knows that food allergies run in families, surprisingly, different family members are often allergic to different foods. And it happens that only a few foods are responsible for the great majority of food allergies. In fact, only eight foods account for more than 90 percent of all food-allergic reactions. These are milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts (walnuts, cashews, and so on), fish, shellfish, soy, and wheat.

These two concepts underlie the elegance and relevance of an allergy cookbook. By featuring recipes that omit all of the least-tolerated foods, a family can share these meals even if one child has a peanut allergy and another has a soy allergy and the celiac neighbor comes over with his lactose-intolerant girlfriend. As a well-known chef and the mother of a food allergyridden boy, Cybele Pascal is uniquely qualified to develop recipes that meet all the common food restrictions without compromising any taste. In 2006 she wrote the popular

first learned about food allergies when I was six years old. The family that lived across the street had four children; the youngest was nicknamed Eggs. I didnt know who first called him Eggs; all I knew was that he couldnt eat eggs and that he was constantly itching his arms and legs, which were covered with thick, scary-looking skin that scabbed. I didnt know anybody else like that; in fact, I was actually more familiar with kids with polio. It wasnt until I was a third-year medical student working in pediatric dermatology that I saw a second person with food allergies. Three years later, when I worked in the Bronx during my residency, I saw more cases of food allergy, mostly in children rushed to the emergency room with hives or wheezing after eating a food they were allergic to.

first learned about food allergies when I was six years old. The family that lived across the street had four children; the youngest was nicknamed Eggs. I didnt know who first called him Eggs; all I knew was that he couldnt eat eggs and that he was constantly itching his arms and legs, which were covered with thick, scary-looking skin that scabbed. I didnt know anybody else like that; in fact, I was actually more familiar with kids with polio. It wasnt until I was a third-year medical student working in pediatric dermatology that I saw a second person with food allergies. Three years later, when I worked in the Bronx during my residency, I saw more cases of food allergy, mostly in children rushed to the emergency room with hives or wheezing after eating a food they were allergic to.