A M AIN S TREET B OOK

PUBLISHED BY DOUBLEDAY

a division of Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc.

1540 Broadway, New York, New York 10036

M AIN S TREET B OOKS , D OUBLEDAY , and the portrayal of a building with a tree are trademarks of Doubleday, a division of Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Poses, Steven

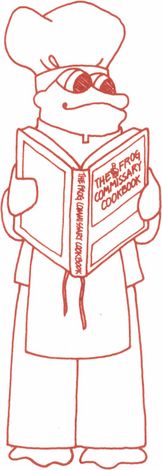

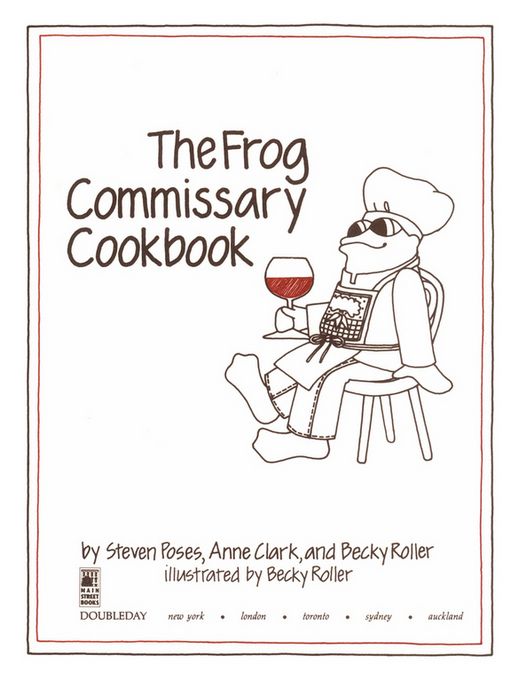

The frog commissary cookbook.

1. Cookery. I. Roller, Rebecca. II. Title.

TX715.P863 1985 641.5

eISBN: 978-0-307-82644-2

Copyright 1985 by The Commissary Inc.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

v3.1

Contents

Introduction

The Frog/Commissary Cookbook is a useful compilation of flavorful and often unusual recipes. The recipes are at once sophisticated, highly accessible, and generally easy to follow. The cookbook is a result of the efforts of scores of exciting cooks who have worked in a family of unique restaurants in what has become one of Americas most interesting restaurant citiesPhiladelphia. In addition to the recipes, the cookbook attempts to communicate an attitude about food, the service of food, the operation of those restaurants, and in its own way, it tells a story about an era in contemporary American culture. It is not like any other cookbook that you own.

I had not always wanted to cook and run restaurants. I grew up in Yonkers, New York in a fairly prosperous and sheltered setting. I came to Philadelphia in 1964 as a freshman at the University of Pennsylvania with a strong desire to be an architect. Fairly early in my undergraduate training I encountered difficulty in a freehand drawing class and concluded that I was not cut out to be an architect. In the very socially conscious period of the mid-sixties, I concluded that my interests lay more in people and the cities they inhabited than in buildings per se, so a change in career direction made some sense.

A key book for me at that time was Jane Jacobss Death and Life of Great American Cities. Jacobs wrote about the role neighborhood candy stores played in defining a community. It was often the neighborhood candy store that provided people with a way to define and connect with their neighborhood. The candy store was symbolic of numerous small elements that helped break down the anonymity of cities. I graduated from Penn with a sociology degree and a strong interest in contributing to the kind of positive urban life that Jacobs presented.

During my college years, I developed an interest in cooking. My mother was a very good cook, and at an early age I came to appreciate good food and the pleasure that can result from serving it. Without my mothers cooking in college, I had both the need and opportunity to learn how to cook. A summers long trip provided extraordinary exposure to the wonderful food of France, Spain, and Italy and whetted my appetite to be able to produce such food. I subscribed to the then new Time-Life Series of International Cookbooks and began experimenting.

My love of cooking and a vision of contributing to urban life was coming together as an idea for a restaurant that could serve the same role as Jane Jacobss neighborhood candy store. It would be the sort of restaurant where people would come together over good food and wine and discuss the great issues of the day. The restaurant would provide a sense of place for people. I would do the cooking.

I knew that I needed experience before I could open a restaurant, so after a brief stint in the Peace Corps and peace movement, I answered a newspaper advertisement for a busboy. I was offered the job if I agreed to cut off my beard. I did. For the next six months, I was the busboy and glass polisher at La Panetire, then Philadelphias most elegant French restaurant.

I really wanted to cook. A position opened up in La Panetires kitchen. I peeled carrots and potatoes, cleaned mussels, pulled feathers out of pheasants, shaped turnips, chopped parsley, and eventually got to saut vegetables on the cooking line. I was now doing some serious cooking. I invested in Julia Childs Mastering the Art of French Cooking. I kept it by my bed and it became my bible.

Much of what I had been cooking, both at La Panetire and at home on my one night off, was very conventional with familiar Western flavors and ingredients. Though my parents parents were Eastern European Jews, my real culinary heritage was a curiously neutral result of growing up suburban in the postwar assimilationist era of the fifties and sixties. La Panetires approach to cooking was classic French. The experimentation of Bocuse, Grard, and the brothers Troisgros that would soon explode as Nouvelle Cuisine and open French cooking to broader influences, was taking place in the isolation of their French kitchens.

The Vietnam War was going on and there were a number of young men from Thailand working in La Panetires kitchen. The exposure to the exotic tastes of Thailand while sharing the staff dinners that they prepared was a revelation: sweet and fiery, red, green, blue and orange curries; pickled vegetables and preserved radish; lemongrass and fish sauce. The Thais with whom I worked and slurped noodles introduced me to the Orient and a particularly exotic corner of it, at that.

Only in America and only at that time could a Jewish kid from Yonkers, having graduated from the University of Pennsylvania, be working and learning how to cook in a French restaurant alongside a substantial contingent of Thais. And my lack of a strong culinary tradition created an openness to a vast world of ingredients, tastes, textures, and methods of cooking. The Frog/Commissary Cookbook is very much a result of this new heritage, whose origin was in the kitchen of La Panetire. Its recipes and spirit continued to be influenced by a long list of young cooks whose parents were Italian, Irish, German, Japanese, Chinese, Vietnamese, or Iranian. We have all worked together, sharing culinary traditions in evolving a rich, new, and curiously friendly multicultured cuisine. We never sought originality for its own sake nor were we ever limited by adherence to tradition. Our simple guiding principle was Does it taste good? The recipes evolved this way and have been refined in the crucible of the highly competitive, very sophisticated, and greatly appreciative restaurant market of Philadelphia over the past twelve years.

Anne Clark was our test chef when the commitment to go ahead with a cookbook was made. In my strongest early recollection of Anne, she sat at table 25 at Frog with one of her twin sons and curled chocolate to garnish a peanut butter pie she had baked for us at her home. Anne was one of a corps of home bakers who prepared desserts for Frog in the early days. Anne loved to bake.

As Frog got busier and Annes twins got older, she came to work in our kitchen as a baker. When The Commissary opened, she was head baker. It was she who developed the tradition of great desserts in all our restaurants. Anne developed our Carrot Cake, Strawberry Heart Tart, Chocolate Mousse Cake, and numerous other now classic desserts. Today, The Commissary employs ten bakers to keep up with the demand.

One night over dinner in Chinatown, Anne asked if there might be a role for her outside of the bakery. While she loved to bake, she also loved to cook. The Commissary had been running a series of loosely organized but successful cooking classes that I thought could stand some order and expansion. In addition, because the kitchen staff was constantly experimenting with new dishes, I was worried about quality control. I offered Anne the position of our first testing chef. She went on to become the general manager of The Commissary.