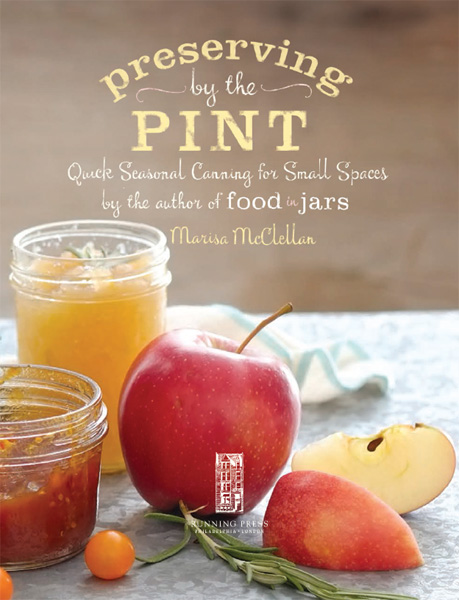

Copyright 2014 by Marisa McClellan

Photographs 2014 by Steve Legato

Published by Running Press, A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved under the Pan-American and International Copyright Conventions

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without written permission from the publisher.

Books published by Running Press are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013943528

E-book ISBN 978-0-7624-5180-7

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Digit on the right indicates the number of this printing

Cover and interior design by Amanda Richmond

Edited by Kristen Green Wiewora

Typography: Clarendon, Helvetica Neue, and New Cuisine

Running Press Book Publishers

2300 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19103-4371

Visit us on the web!

www.offthemenublog.com

This book is dedicated to my husband, Scott. Neither this volume, nor my career as a food writer, would exist without his endless love, encouragement, and support.

This cookbook is for people who

live in cities and have tiny kitchens.

Its for newlyweds, empty nesters, and other households

of just one or two. Its for CSA subscribers who love

supporting their local farmers but who struggle to eat through

their share each week. Its for parents who want to get their

young kids involved in canning, but cant keep short attention

spans focused for more than ten minutes. Its for gardeners

with postage-stamp-size plots and for farmers market

regulars. And its for anyone who wants to dip a toe

into the world of food preservation.

Maybe its for you.

Contents

W hen I first started canning, I made huge batches of jam. Between the cleaning, peeling, and chopping, Id be dripping with sweat and every inch of my kitchen would be covered in sticky fruit residue. Despite the fact that each jamming session took hours and hours, I did it that way because thats just how I thought canning was supposed to be. After all, every traditional recipe I found yielded five or seven or nine pints of jam. I just didnt see how it could be done any other way.

However, at the end of that first year, I discovered that even after eating jam on a daily basis and giving away many, many jars, I was still swimming in preserves. I knew that I really enjoyed the process of putting up, so giving it up until the first years jams were gone wasnt an option. I needed to find a way for it to take less time and yield smaller amounts.

And so I started tearing down the recipes, dividing the amount of produce required and finding pieces of cookware that worked best with these small batches. I also developed techniques for breaking up the work, so that I could do it when it was most convenient for me without sacrificing freshness.

These days, I do a lot of very small batches. The jams, jellies, and chutneys yield just two or three half-pint jars, as do my batches of pickles. I also do a lot of preserving that doesnt include the canning pot at all, but instead are simply designed to buy me a few extra days or weeks with a bundle of herbs or a dry quart of Kirby cucumbers. Preserving on this scale means that I get to explore different flavor combinations without ever committing massive amounts of produce to an idea that might not work out. It also allows me to have three or four dozen different kinds of jams, conserves, and sauces in my pantry. I really enjoy having that kind of breadth and I have a feeling that there are a lot of other people who might just appreciate it as well.

TECHNIQUE

There are a number of very handy things about preserving in small batches. Because youre only dealing with modest quantity of produce, the preparation goes fast. Whats more, a number of the recipes call for you to let the fruit sit and rest for a time with the sweetener after youre done peeling and chopping and pitting. If youve run out of time on that particular day, its at this point that you can cover your bowl and pop the fruit into the fridge to macerate for 12 to 24 hours. They also cook quickly, particularly if you use wide pans. Best of all, because were cooking in such small batches, these preserves tend to be lower in added sugar than are more conventional recipes, because you just dont need as much to sugar to support the set.

COOKWARE

There are just three pieces of cookware that I really recommend if want to do these tiny batches. The first is a basic, 12-inch (30.5 cm) stainless-steel skillet. This is an amazing pan for cooking small batches of jam. The wide base gives the fruit a lot of surface area on which to cook and the short, sloped sides encourage evaporation. Four cups/910 g of combined fruit and sugar take just 7 or 8 minutes to cook to a jammy consistency in a wide skillet.

Stainless steel, anodized aluminum, or enameled cast iron are the best materials to choose for these acidic preserves because they wont leach metallic flavors into your jam. Cast iron and aluminum can give jam a tinny taste. Nonstick is acceptable, but I find that its much harder to tell when batches of jam are nearing completion on a nonstick surface.

For some of the slightly larger batches, or for recipes that cook down longer, I find that a 5-quart /4.8-liter Dutch oven is a really good pot for the job. You dont have to get a fancy enameled one: I have an inexpensive stainless-steel version that is perfectly sturdy.

The final piece of cookware that makes for easy small batches is a tall, skinny pot, preferably fitted with a rack. Asparagus pots do the job nicely, but my favorite is what Kuhn Rikon calls a 4TH burner pot. It works well as either a processing pot (you can fit either two wide-mouth or three Ball Collection Elite half-pint/250 ml jars in it) or as a pot for heating up pickling liquid. Thanks to the pour spout and coated handle, you can heat the vinegar in it and then pour directly into the prepared jars. I am very fond of this little pot. When it comes to processing slightly larger batches, an 8-quart/7.6-liter nonreactive stockpot fitted with a stainless-steel rack on the bottom does the job. The most important thing is that its deep enough so that the jars are fully submerged with an inch/2.5 ml of water covering them, with room for the water to boil. The jars should not rest directly on the bottom of the pot, as the direct heat could cause them to crack. Whats more, the rack permits the water to circulate around the jars, which allows for complete heat penetration and sterilization.

Next page