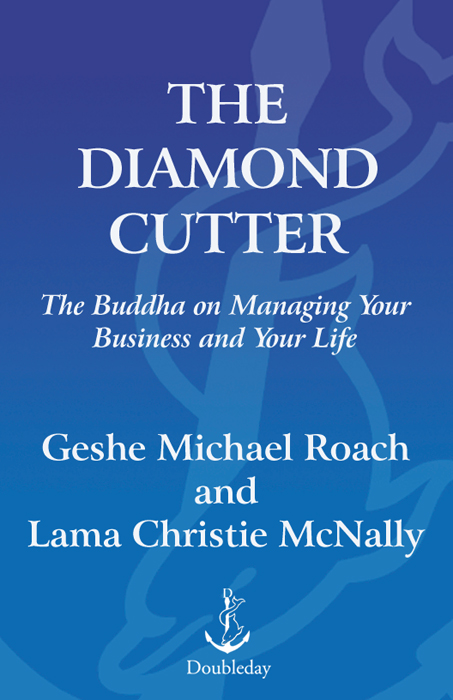

Foreword

The Buddha

The Buddha

and BusinessD uring the seventeen years from 1981 to 1998, I had the honor of working with Ofer and Aya Azrielant, the owners of the Andin International Diamond Corporation, and the core staff of the company to build one of the worlds largest diamond and jewelry firms. The business was started with a $50,000 loan and only three or four employees, including myself. By the time I left to devote full time to the training institute I had founded in New York, our sales were in excess of 100 million U.S. dollars per year, with over five hundred employees in offices around the world.

During my time in the diamond business, I led a double life. Seven years before joining the trade, I graduated from Princeton University with honors, having previously received the Presidential Scholar Medallion from the President of the United States at the White House, and the McConnell Scholarship Prize from Princetons Woodrow Wilson School of International Affairs.

A grant from this school allowed me to travel to Asia, for study with Tibetan Lamas at the seat of His Holiness, the Dalai Lama. Thus began my education in the ancient wisdom of Tibet, which culminated in 1995, when I became the first American to complete the twenty years of rigorous study and examinations required to earn the ancient degree of geshe, or master of Buddhist learning. I had lived in Buddhist monasteries both in the United States and Asia since graduating from Princeton, and in 1983 taken the vows of a Buddhist monk.

Once I had gained a firm foundation in the training of a Buddhist monk, my principal teacherwhose name is Khen Rinpoche, or Precious Abbotencouraged me to enter the world of business. He told me that, although the monastery was an ideal place for learning the great ideas of Buddhist wisdom, a busy American office would provide the perfect laboratory for actually testing these ideals in real life.

I resisted for some time, hesitant to leave the quiet of our small monastery, and nervous about the image of American businessmen in my mind: greedy, ruthless, uncaring. But one day, after hearing my teacher give an especially inspiring talk to some university students, I told him I would agree to his instructions and seek a job in business.

Some years earlier I had had something of a vision at the monastery during my daily meditations, and I knew from that time what business I would choose to work in: It would surely involve diamonds. I had no knowledge of these gemstones, and frankly no attraction whatsoever to jewelry; neither had any of my family ever been involved in the trade. So, like the innocent Candide, I began visiting one diamond shop after another, asking if anyone would be willing to accept me as a trainee.

Trying to join the diamond business this way is a little like attempting to sign up for the Mafia: the raw diamond trade is a highly secretive and closed society, traditionally restricted to family members. In those days, the Belgians controlled the larger diamondsthose of a carat or more; the Israelis cut most of the smaller stones; and the Hassidic Jews of New Yorks Diamond District on Forty-seventh Street handled the majority of the domestic American wholesale trade.

Remember that the entire inventory of even the largest diamond houses can be contained in a few small containers that look a lot like ordinary shoe boxes. And there is no way to detect a theft of millions of dollars of diamonds: you just put a handful or two in your pocket and walk out the doorthere is nothing like a metal detector that can spot the stones. And so most firms hire only sons or nephews or cousins, never an odd Irish boy who wants to play with diamonds.

As I remember, I visited some fifteen different shops, asking for an entry-level position, and was summarily thrown out of each of them. An old watchmaker in a nearby town advised me to try taking some courses in diamond grading at the Gemological Institute of America in New York; Id be more likely to get work if I had a diploma, and might meet someone in the classes who could help me.

It was at the institute that I met Mr. Ofer Azrielant. He was also taking a class in grading very high-quality diamonds, known as investment or certificate stones. Distinguishing an extremely valuable certificate diamond from a fake or treated stone involves being able to spot tiny holes or other imperfections the size of a needle point, while dozens of dust motes land on the surface of the diamond, or on the lens of the microscope itself, to parade around and confuse things. So we were both there to learn how not to lose our shirts.

I was impressed immediately by Ofers questions to the teacher, by how he examined and challenged every concept presented. I determined to try to get him to help me find a job or even hire me himself, and so struck up an acquaintance. A few weeks laterthe day I finished my final exams in diamond grading at the New York labs of the GIAI made up an excuse to get into his office and ask him for a job.

By great good luck he was at that moment just opening a branch office in America, having already founded a small firm in Israel, his home. So I talk my way into his office and beg him to teach me the diamond business: Ill do anything you need, just give me a try. Ill straighten up the office, wash the windows, whatever you say.

And he says, I dont have any money to hire you! But tell you what, Ill talk to the owner of this officehis name is Alex Rosenthaland well see if he and I can split your pay between us. Then you can do errands and things for us both.

So I start as an errand boy, at seven dollars an hour, a Princeton graduate dragging through steamy New York summers and winter snowstorms on foot, uptown to the Diamond District, carrying nondescript canvas bags filled with gold and diamonds to be cast and set into rings. Ofer, his wife Aya, and a quiet, brilliant Yemeni jeweler named Alex Gal would sit around our single rented desk with me, sorting diamonds into grades, sketching new pieces, and calling around for customers.

Paychecks were few, often delayed while Ofer tried to talk his London friends into some more loans, but soon I had enough to buy my first business suit, which I wore every day for months. We often worked past midnight, and I would have a long trip back to my little room at a small monastery in the Asian Buddhist community of Howell, in New Jersey. In a few hours I would be up again and back on the bus to Manhattan.

After our business had grown a bit, we moved uptown closer to the jewelry district proper, and took the brave step of hiring a single jewelry craftsman, who sat alone in the big room that was our factory, making our first diamond rings. Before long I was trusted enough to get my wish, to sit down with a parcel of loose diamonds and start sorting them into grades. Ofer and Aya asked me if I would take responsibility for the newly formed diamond purchasing division (which at the time consisted of myself and one other person). I was excited at the opportunity, and plunged into the project.