The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my mother and the memory of my father

C ONTENTS

P REFACE

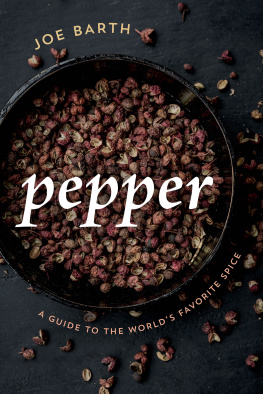

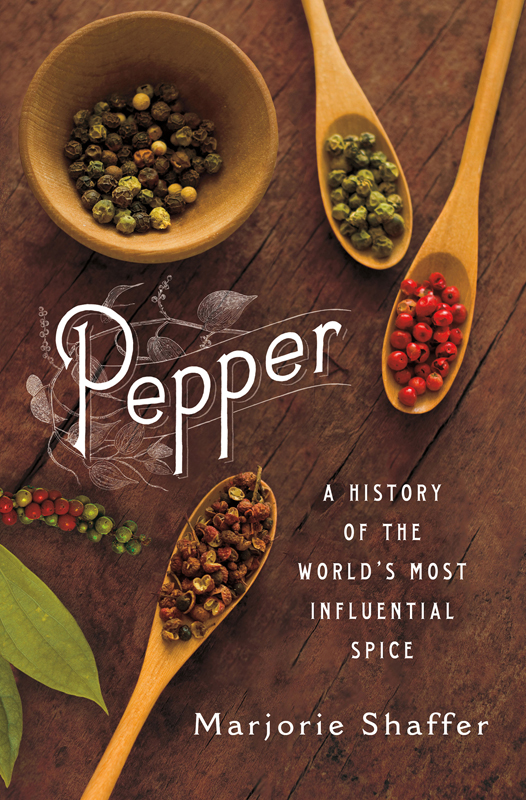

A seasoning used in countless meals for thousands of years, pepper reaches our consciousness with a sharp zing, like a good kick to our taste buds. The spice bursts in the mouth and tickles the back of the throat, announcing itself with a triumphant, unmistakable sharpness. Inhaling the rich aroma of newly ground black pepper can be as intoxicating as sniffing a glass of robust red wine, and today we can savor black pepper from various regions of the world, each carrying its own distinctive flavor.

It is hard to imagine a spice rack without black pepper. The Zelig of the culinary world, the spice insinuates itself into an endless medley of food, creating hot or earthy sensations, depending on where the pepper is grown. Few recipes can resist the spice. Today, you can walk into any food store and usually find an assortment of tins containing ground pepper or jars of brightly multicolored peppercorns to grind at home. Pepper shakers grace the tables of restaurants all over the world.

Although it is a nearly universal spice, many people in the West dont know where pepper comes from and mistakenly believe that it grows on trees. However, if you were raised in Kerala, on the southwest coast of India, you would have no problem identifying a pepper plant. It would be as familiar as dandelions crowding a suburban lawn on a summer day in the eastern United States. Black pepper, a vine, thrives naturally only in tropical soils, and its stubborn inability to grow elsewhere is one of the reasons it has had such an impact on world history.

* * *

I first saw a pepper plant in the greenhouses of the University of Connecticut in Storrs, where I wandered around admiring a rich array of strangely ornamental tropical plants. A week earlier, a corpse plant, a giant that grows in Indonesia and shoots up like a spaceship (and in Latin is aptly named Amorphophallus titanum) , had blossomed in one of the greenhouses. Luckily, I wasnt there for the actual flowering, which sends out a horrible stench, hence the name corpse plant. By comparison, the pepper plant was diminutive and rather drab. But when I considered how the modern age of trade and trades pernicious twined branches, colonialism and imperialism, evolved from this rather prosaic organic substance, a simple condiment, a seasoning that everybody uses, I thought its modest appearance was deceiving.

I originally had wanted to write about the Jesuits who served in the court of Chinese emperors as repairers of elaborate mechanical clocks in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and I spent several years combing through scholarly articles and books about these fascinating men. As I slowly got my bearings, I became intrigued by the movement of Europeans into Asia, the means by which they got there, and the primary reasons they went. These questions led to black pepper. If you follow the early tracks of Europeans to the East, you inevitably run into the spice.

Eventually I put aside the Jesuits and focused on the spice, which opened entirely new worlds. My invaluable guides were the extraordinary historians who have written about pepper. They led me to the journals of the European traders who had traveled to Asia during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which became important sources for telling the story of pepper. As much as possible, eyewitness accounts provided the historical setting and conveyed whenever possible what it was like for these Europeans to meet people from other cultures. These accounts are culled from the journals of merchants and sailors who were employed by the Dutch and English East India Companies, and from the logbooks of sailors aboard American ships that sailed to Indonesia in the nineteenth century to buy pepper.

Some of these journals have now been digitized, so it is no longer necessary to read the material in its original form. It is still thrilling, though, to hold in ones hands a journal or ships log written hundreds of years ago. Perusing these journals is one of the pleasures of historical research: You never know what you will find. There was a perennial preoccupation with food, for instance, as revealed in European sailors numerous, colorful descriptions of fish, birds, and other animals encountered in Asia. Like other meetings between the West and Asia, this one ended in destruction. The extinction of the dodo is related to the pepper trade, and a chapter in the book is devoted to the frenzied killing of animals in Asia by European traders.

The book follows the Portuguese, who first sailed to India around the Cape of Good Hope, and then tracks the English, Dutch, and Americans to Asia. The Indonesian islands of Sumatra and Java were essential destinations for procuring pepper, and on these islands a substantial portion of the story of pepper unfolds. The longest chapters are devoted to the English and Dutch, whose loathing for one another drove so much of the history of pepper and of empire in Asia. The two-hundred-year-long rivalry between the English and Dutch East India Companies also shaped the momentum of modern global trade with its never-ending need to exploit foreign resources to satisfy local markets. The Indiamen, as the sailing ships of the northern European companies were called, were the early forerunners of the giant container ships that today ply the worlds oceans. The Strait of Malacca, a crucial waterway in the pepper trade, is still the shortest route between India and China and is still a dangerous place to move cargo. There are many other ways in which the story of pepper resonates in the modern world.

The last chapter brings the story full circle with a survey of modern-day scientific investigations of peppers medicinal properties. Thousands of years ago, pepper was renowned as a cure-all for disease, and only later did it become a condiment. Scientists today are discovering that the spice affects human health in manifold ways, a validation of peppers role in the apothecaries of the ancient Greeks and Romans, as well as in the medicinal systems of China and India.

Geography plays such a crucial role in the story of pepper that it would be remiss not to include maps of the Indian Ocean, India, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Many of the ports where the pepper trade was conducted are unfamiliar to Western readers. I constantly had to refer to maps in order to figure out where the story of pepper had taken me, and I hope that the maps in the book help orient readers. Nowadays, Google can find the location of nearly any place on earth, but you still have to have a reason to look. How many people in the West know where South Sulawesi and Malaysia are, or have heard of Malacca?

This book isnt a comprehensive history of European pepper trading in Asia. For those who wish to pursue certain topics in more depth, there is a rich literature. Instead, this book attempts to illuminate history through the desire for a single substance. Why pepper? Why does this common commodity, the ever-present companion of salt, merit attention? How could history be explained through pepper? I hope that this book answers these questions.