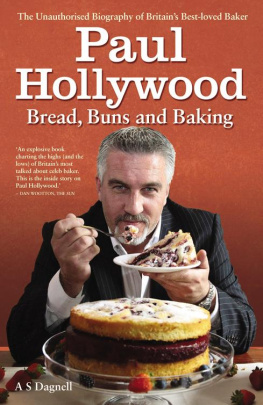

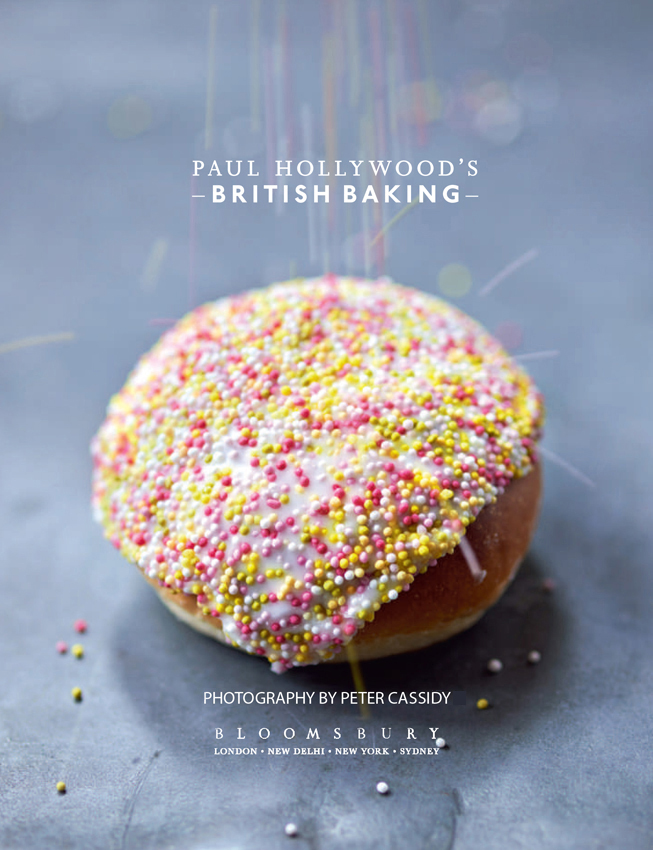

Paul Hollywood - Paul Hollywoods British baking

Here you can read online Paul Hollywood - Paul Hollywoods British baking full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London, year: 2014, publisher: Bloomsbury, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Paul Hollywoods British baking

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- City:London

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Paul Hollywoods British baking: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Paul Hollywoods British baking" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Paul Hollywoods British baking — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Paul Hollywoods British baking" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For Alex

NOTE

My baking times in the recipes are for conventional ovens. If you are using a fan-assisted oven, you will need to lower the oven setting by around 1015C. Ovens vary, so use an oven thermometer to verify the temperature and check your bakes towards the end of the suggested cooking time.

List of recipes by type

SAVOURY PIES, PASTIES & PUDDINGS

SCONES, GRIDDLE SCONES & PANCAKES

BREADS

SWEET YEASTED BREADS

SWEET PIES & PUDDINGS

SWEET TARTS & PASTRIES

CAKES & TEABREADS

BISCUITS & TRAYBAKES

I ntroduction

Ive been lucky enough to work all over the country as a baker, and everywhere I go, I see a passion for baking. I like to find out what people bake at home and they love to tell me. Sometimes I learn about the cakes their grandmother made or they give me a family recipe. Each generation tweaks the recipe a bit to make it their own, but it retains the character of the original. You can almost trace a familys history through a recipe thats been handed down through the generations.

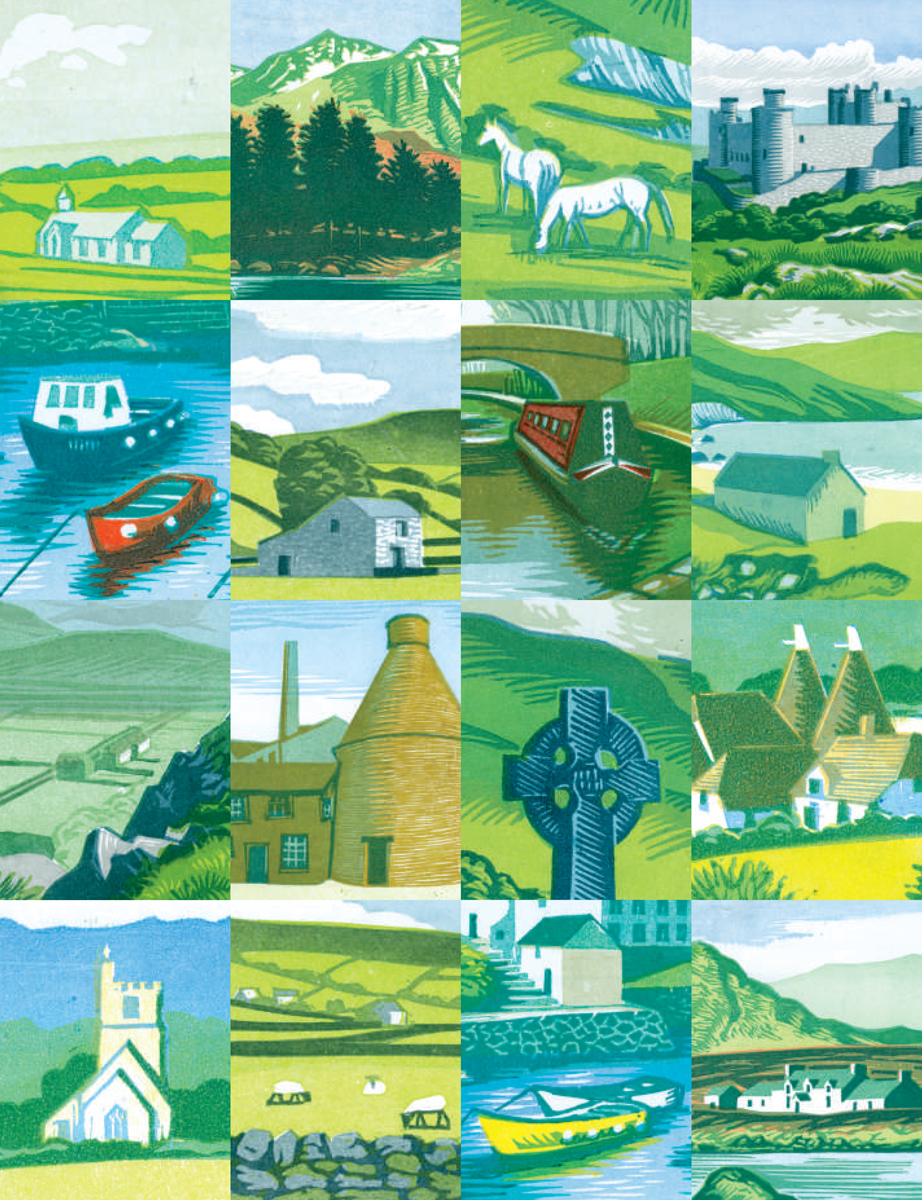

In the same way that families have their own baking tradition, so do the different parts of the British Isles and to celebrate this diversity, the recipes in this book are divided up by area. I hope youll turn to the chapter for the place where you live and think, Oh, I remember that, or I never thought of cooking that, Ill give it a go. But I also hope that youll try the cakes, pies, puddings, breads and biscuits of other regions too, and find some new favourites. The first time you make a recipe, its best to stick to it closely, but afterwards you might like to change it and make it your own, perhaps even creating a new tradition.

The charm and variety of baking in Scotland, England, Wales and Ireland is reflected in some of the old names. In this book youll find huffkins, chudleighs and churdles; wiggs and fairings; plough pudding and fidget pie; bara brith and petticoat tails. Often the stories behind these names feature bakes that came about by accident when a cook misinterpreted a recipe, perhaps, or when something was dropped and miraculously tasted wonderful. Or they denote a moment in history, such as Henry VIII finding Anne Boleyn and her ladies-in-waiting tucking into little pastries and naming them Maids of Honour on the spot. Whether the stories are true or not, they tell us something about our past and the significant role that baking has played in peoples lives.

Although the baking of the British Isles is surprisingly diverse for a relatively small area, I have always been struck by the similarities from region to region too. Everywhere you go, youll find common threads, such as griddle baking, steamed puddings, raised pies and enriched breads. Small adjustments give these things their regional character. In the North of England, for example, they like their breads, pies and cakes to be baked darker than in the South, while in the Southwest, baking tends to be that little bit more refined than elsewhere.

I find it fascinating to look at the history of baking in this country and discover how these similarities and differences arose. Long ago, the local baker determined how things were done and people would come to think that was the way they should be done. Bakers liked to keep their recipes secret, as they werent keen to encourage their customers to bake at home. Many of the variations you find in domestic cooking are interpretations of what was on sale at the local bakery.

Fundamentally, baking relies on a few simple ingredients: flour, fat, perhaps eggs, a raising agent such as yeast or baking powder and, for sweet bakes, sugar. In medieval times, wholemeal flour and flour made from other grains, such as rye, were standard for everyone except the wealthy. It was not until the Georgian era that refined white flour became relatively affordable. Flour grown in the British Isles is quite weak, which makes it ideal for cakes and biscuits, less so for bread.

In Scotland and the North, oats and barley were the dominant grains. Although barley is much less common now, oats still feature strongly in Scottish , which would be considered rolls, baps or buns elsewhere in the country.

It is easy to see how the geography and farming of an area have shaped its baking traditions. Whether you used butter or lard in your cooking would have depended partly on income but also on the local farmland. In the Southwest, where there was good grazing for cows, butter and milk were plentiful, resulting in richer breads, cakes and biscuits. In regions such as East Anglia, where every smallholder kept a pig, lard was the fat of choice. Cheap and nutritious, it was also a means of using every last bit of the animal.

In the Southwest, cider, apples and clotted cream all find their way into baking, while in Kent, cherries are used in cakes and puddings to an extent that you simply dont find elsewhere. Scotland has virtually built its baking on oats, which grow so well in its cool, wet climate, and in Ireland the potato plays a unique role in breads and other baked goods. But some of the ingredients that play the biggest part in adding flavour and character to our baking are not indigenous at all.

Take sugar, for example. Its hard to imagine life without it but, until sugar cane was first imported from Barbados in the early 17th century, we had to rely on honey a seasonal, costly ingredient for sweetness. The availability of sugar changed everything, and Britains dominance of the Caribbean gave us the monopoly on it for over a century. The dark side of sugar is that it was, of course, built on the slave trade.

Sugar remained expensive until the 19th century. Surprisingly, it is Napoleon we have to thank for the drop in price. When the British enforced a trade blockade during the Napoleonic Wars, he encouraged sugar beet production in France. Eventually this started to be cultivated in various parts of the British Isles too, though we still imported much of our sugar from the colonies. Suddenly everything was sweetened, from cups of tea to childrens treats. Sugar was now a necessity rather than a luxury, becoming so cheap that it went from being the preserve of the rich to one of the mainstays of the working-class diet.

Yet, even before we had sugar to sweeten our bakes, we had dried fruit. Its impossible to imagine British baking without currants, raisins and sultanas. Eccles cakes, curd tarts, teabreads, mince pies, fruit cakes these are uniquely British. Perhaps the key to why weve always used so much dried fruit is that it keeps for ages and is easy to transport. It was brought back to Britain by the Crusaders and became a flourishing trade in Tudor times the classic English plum pudding was invented at the end of the 16th century. By the mid-19th century, dried fruit was cheap enough to be available to everyone. It was in the Victorian era that Christmas became widely celebrated in the way we know today, with all the festive baking and dried fruit consumption that entails.

Spices were another import that helped shape the character of our baking. Brought into ports such as Liverpool, Whitehaven, London and Bristol, they have had a tremendous impact on our cooking. One of the strengths of our cuisine is that weve never been afraid to borrow from other cultures, taking a little bit of this and a little bit of that to brighten things up. So it was with spices such as ginger, cinnamon, mace, nutmeg and caraway. Gradually, these imports bled into indigenous recipes and became part of the blueprint of British baking. In the past, spices like these not only added flavour but were also a useful way to disguise the strong taste of the yeast, or barm, which was taken from the top of beer.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Paul Hollywoods British baking»

Look at similar books to Paul Hollywoods British baking. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Paul Hollywoods British baking and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.