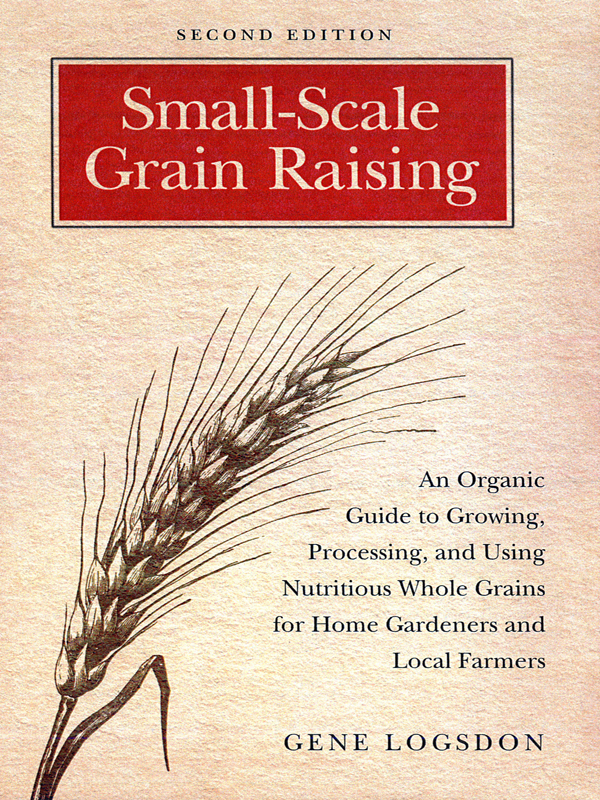

Small-Scale

Grain Raising

Small-Scale

Grain Raising

SECOND EDITION

Gene Logsdon

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

JerryOBrien

CHELSEA GREEN PUBLISHING

WHITE RIVER JUNCTION, VERMONT

Copyright 2009 by Gene Logsdon. Original

edition published in 1977 by Rodale Press, Inc.,

Emmaus, Pennsylvania.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be

transmitted or reproduced in any form by any

means without permission in writing from

the publisher.

All photographs by Gene Logsdon unless

otherwise credited.

All illustrations by Jerry OBrien, unless

otherwise credited.

Project Manager: Emily Foote

Developmental Editor: Ben Watson

Copy Editor: Cannon Labrie

Proofreader: Helen Walden

Designer: Peter Holm, Sterling Hill Productions

Printed in the United States of America

Second Edition. First printing, March, 2009

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 10 11 12 13 14

Our Commitment to Green Publishing

Chelsea Green sees publishing as a tool for cultural change and ecological stewardship. We strive to align our book manufacturing practices with our editorial mission and to reduce the impact of our business enterprise on the environment. We print our books and catalogs on chlorine-free recycled paper, using soy-based inks whenever possible. This book may cost slightly more because we use recycled paper, and we hope youll agree that its worth it. Chelsea Green is a member of the Green Press Initiative (www.greenpressinitiative.org), a nonprofit coalition of publishers, manufacturers, and authors working to protect the worlds endangered forests and conserve natural resources.

Small-Scale Grain Raising, Second Edition was printed on 60-lb. Joy White, a 30-percent postconsumer-waste recycled paper supplied by Thomson-Shore.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Logsdon, Gene.

Small-scale grain raising : an organic guide to growing, processing,

and using nutritious whole grains for home gardeners and local farmers / Gene Logsdon. -- 2nd ed.

p. cm.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-60358-216-2

1. Grain. 2. Organic farming. 3. Farms, Small. 4. Cookery (Cereals) I. Title.

SB189.L79 2009

633.10484--dc22

2009000820

Chelsea Green Publishing Company

Post Office Box 428

White River Junction, VT 05001

(802) 295-6300

www.chelseagreen.com

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION TO

THE SECOND EDITION

When this book was first published in 1977, I suspected, but could not know for sure, that a day would come when increasing populations and increasing costs of producing and transporting food with fossil fuel, fossil fertilizers, and genetic manipulation would cause food prices to rise so high that more traditional production methodsorganic, natural, low-labor, and localwould begin to rule the economy. Thirty years later, that is exactly what is happening. Whenever in history a new, more economical way to do anything is discovered, it will take over the market, no matter how hard entrenched big business and government try to stop it. Not all the forces of power, with their sickening subsidy mentality for the rich, can prevail forever against economic reality.

This book is intended for the pioneers of this new, low-cost way of making foodthose gardeners and garden farmers or cottage farmers who are interested in increasing both the quantity and quality of their homegrown food supply by incorporating whole grains and dry beans into their fruit and vegetable growing systems. I am not writing this for commercial grain producers, who know far more about their business than I do. I cant even drive one of those huge and complicated tractors that can plow an acre a minute. Nor do I wish to denigrate commercial farmers: Some of them are close friends. While I fear that their way of agriculture cannot ultimately sustain itself, we would be in desperate straits right now without these farmers. I would hope that these larger-scale farmers would find ideas and viewpoints here interesting and perhaps persuasive, especially if they are organic or natural farmers. But the methods I describe and argue in favor of do not promise what the agricultural experts call top profits, but only good food and the satisfaction of producing it on a scale that society can afford.

We have become a nation dangerously dependent on politically motivated and money-motivated processes for our food, clothing, and shelter. In the world we must live in from now on, to produce our own food is the beginning of independence. To accept that responsibility is the first step toward real freedom.

I remember the first year we grew grains in our garden. A good gardening buddy dropped by one day early in July just when our wheat was ripe and ready to harvest. He didnt know that though. His reason for stopping was to show me two splendid, juicy tomatoes picked ripe from his garden. After a few ritual bragsand knowing full well that my tomatoes were still greenhe asked me in a condescending sort of way what was new in my garden. I remembered the patch of ripe wheat. Oh, nothing much, I answered nonchalantly, except the pancake patch.

The pancakepatch? he asked incredulously.

Yeah. Sure. Until youve tasted pancakes fresh from the garden, you havent lived.

And where might I find these pancakes growing? he queried sarcastically, to humor my madness.

Right up there behind the chicken coop in that little patch of wheat. All you have to do is thresh out a cupful or two, grind the grain in the blender, mix up some batter and into the skillet. Not even Aunt Jemima in all her glory can make pancakes like those.

My friend didnt believe me until I showed him, step by step. We cut off a couple of armloads of wheat stalks, flailed the grain from the heads onto a piece of clean cloth (with a plastic toy ball bat), winnowed the chaff from the grain, ground the grain to flour in the blender, made batter, and fried pancakes. Topped them with real maple syrup. Sweet ecstasy. My friend forgot all about his tomatoes. The next year, he invited me over for grain sorghum cookies, proudly informing me that grain sorghum flour made pastries equal to, if not better than, whole wheat flour. Moreover, grain sorghum was easier to thresh. I had not only made another convert to growing grains in the garden, but one who had quickly taught me something.

Grow Your Own Grains

The reason Americans find it a bit weird to grow small plots or rows of grain in gardens is that they are not used to thinking of grains as food directly derived from plants, the way they view fruits and vegetables. The North American, unlike most of the worlds peoples, especially Asians and Africans, thinks grain is something manufactured in a factory somewhere. Flour is to be purchased like automobiles and pianos. Probably this attitude came from the practice of hauling grains to the gristmill in past agrarian times. Without the convenience of small power grinders and blenders of today, overworked housewives of earlier times were only too glad to have hubby haul the grain to the gristmill. And that gave him an excuse to sit around all day at the mill talking to his neighbors.

But even with the advent of convenient kitchen aids to make grain cookery easier, the American resists. He will work hard at the complex task of making wineseldom with a whole lot of successbut will not grind whole wheat or corn into nutritious meal, a comparatively easy task. I know, because I was that way myself. Until I saw with my own eyes that a good ten-speed blender or kitchen mill could turn grain into flour, I hesitated. Now it boggles my mind to remember that for most of my life I lived right next to acres and acres of amber waves of grain, where combines made the threshing simplicity itself, and yet our family always bought all our meal and flour.

Next page