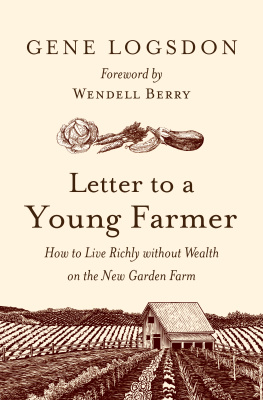

THE CONTRARY FARMER

GENE LOGSDON

THE

CONTRARY

FARMER

Contents

CHAPTER 1

At Ease with the Work of Farming

CHAPTER 2

Pastoral Economics

CHAPTER 3

The Garden is the Proving Ground for the Farm

CHAPTER 4

The Peaceable Kingdom of the Barnyard

CHAPTER 5

Water Power

CHAPTER 6

A Paradise of Meadows

CHAPTER 7

Groves of Trees to Live In

CHAPTER 8

King Corn

CHAPTER 9

Cottage Mechanics

CHAPTER 10

Winter Wheat, Spring Oats, Summer Clover, Fall Pasture

This book is dedicated to my friend, Dave Smith, on whose contrary farm the marauding wild boars understand retribution but the old redwoods grow peacefully, knowing they will not be cut down as long as lie lives.

The Contrariness of the Mad Farmer

I am done with apologies. If contrariness is my inheritance and destiny, so he it. II it is my mission to go in at exits and come out at entrances, so be it. I have planted by the stars in defiance of the experts, and tilled somewhat by incantation and by singing, and reaped, as I knew, by luck and Heaven's favor, in spite of the best advice. If I have been caught so often laughing at funerals, that was because I knew the dead were already slipping away, preparing for a comeback, and can I help it? And if at weddings I have gritted and gnashed my teeth, it was because I knew where the bridegroom had sunk his manhood, and knew it would not be resurrected by a piece of cake. "Dance" they told me and I stood still, and while they stood quiet in line at the gate of the Kingdom, I danced. "Pray" they said, and I laughed, covering myself in the earth's brightnesses, and then stole off gray into the midst of a revel, and prayed like an orphan.

When they said "I know that my Redeemer liveth," I told them "He's dead." And when they told me "God is dead," I answered "He goes fishing every day in the Kentucky River. I see Him often." When they asked me would I like to contribute I said no, and when they had collected more than they needed, I gave them as much as I had. When they asked me to join them I wouldn't and then went off by myself and did more than they would have asked. "Well, then" they said "go and organize the International Brotherhood of Contraries," I said "Did you finish killing everybody who was against peace?" So be it. Going against men, I have heard at times a deep harmony thrumming in the mixture, and when they ask me what I say I don't know. It is not the only or the easiest way to come to the truth. It is one way.

Wendell Berry

from Farming: A Hand Book

Gratitudes

My thanks go first to Dave Smith, to whom this book is dedicated. Co-founder of Smith and Hawken, Dave staked me to the writing of this book both with money and with an indefatigable flow of encouragement. Those who think that American business has grown decadent in the pursuit of self-aggrandizement need to know Dave as well as I have come to know him.

Secondly, a special thanks to Jim Schley, my editor at Chelsea Green Publishing Company. Gawd. There were times when his skill and dedication sent me nearly clawing up the oak tree outside my windowmostly because he was mostly right and I was mostly wrong. If this manuscript reads well to you, the credit should go entirely to Jim's tireless efforts. In fact, so pervasive is his hand in every chapter that I am going to depart from the usual writerly custom and say that any mistakes left are entirely Jim's. Just kidding.

Obviously, for the Contrary Farmer to succeed, he must have a contrary wife and family and a most contrary bunch of relatives and friends. You all know who you are and how much you've helped. And how I can never repay any of you adequately.

I give special thanks to two friends and university teachers, Kamyar Enshayan and David Orr. They are as contrary in academia as I am in agriculture, willing to point out problems in their university establishments with great courage and little regard for their own career security. They are true Teachers, and have inspired me greatly to keep pressing on. If only we had colleges full of people like them, then colleges might make sense again.

The Ramparts People

I remember clearly the day when I was twelve, hunting morel mushrooms with my father, when I informed him excitedly that I had decided to take my dog and my rifle and go deep into the wilderness to live. I would build a cabin on a mountainside by a clear running stream, and live out my days happily on broiled trout, fried mushrooms, and hickory nut pie. I would achieve advanced degrees in the art of living, bestowed on me by Nature, and I would know many things not even Einstein or my stupid schoolteacher dreamed of.

I thought that he would approve, since he was forever retreating to the solitude of woods and river bank and farm field himself. But he almost frowned, suggesting gently in a voice that sounded as if he were saying what he thought he was supposed to say, not what he really felt, that I needed to be thinking about making my way in the world and contributing something to it.

Unfortunately I tried to follow his advice and it took me until I was forty-two to realize that I knew what was better for me when I was twelve. And having hunted everywhere for the peculiar kind of freedom I had tried to articulate that day, I came back to my boyhood homethe place of my beginnings-and found it. What I learned in the process was to follow my own mind because worldly wisdom invariably springs from notions that are largely erroneous. The only really good advice that holds up in all situations is: Always make friends with the cook.

For a while, I thought Americans had lost the desire for independence-the kind of independence that defines success in terms of how much food, clothing, shelter, and contentment I could produce for myself rather than how much I could buy; the kind of freedom that examines the meaning of life, not the meaning of cholesterol; the kind of freedom that allows me to say what I think in public without fear that my words will be "bad for business," the fear that keeps my rich acquaintances in town in silent bondage, trading their freedom of speech for dollars. (Not a one of them will publicly say what they privately be lieve: that President Clinton is as mad as ex-President Bush for dropping "well-intentioned" bombs on defenseless countries, and so the polls all appear to approve an act of outright terrorism.)

Then I started hearing about other people who were even more independent than I dared to dream: people deliberately removing themselves from the protection of the great god, Grid, because only beyond the blessings of the holy public utility could they find affordable land of their own: and also people, excluded from even that kind of frontier, who were turning ghettos into edenic gardens. I became acquainted with a university music professor who farmed with horses and in retirement manufactured modern horsedrawn machinery; a scientist who discovered that composted sewage sludge protects vegetable plants from disease; a man who homesteaded with his family in an isolated rural area to start a million-dollar business creating beautiful and useful items out of waste wood even while a rare disease slowly incapacitated his muscular coordination; a Vietnamese immigrant who figured out how to use duckweed (green pond scum) to purify wastewater and then made a nutritious protein supplement out of the scum; a rock star who bought a thousand-acre farm and turned it back into a wilderness that produces more food than the farm did; a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who quit his career to become an organic market gardener; a famous cartoonist who built a sewage system for his huge office complex that uses the shit and urine from his fifty workers to grow exotic plants, fish, and mussels, and then discharges pure water back into the environment; a contractor who uses scrap tires, earth, and beer cans to build houses that run entirely on the sun.