Copyright 2014 by Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-62087-830-9

eISBN: 978-1-62914-036-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

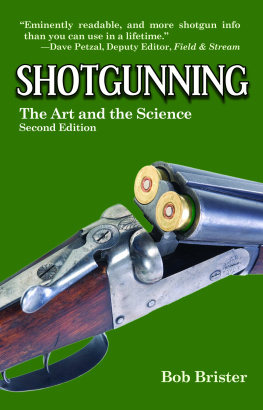

Brister, Bob.

Shotgunning: the art and the science/Bob Brister;

foreword by Grant Ilseng2nd ed.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-60239-327-1 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1. Shotguns. 2. Shooting. I. Title.

SK274.B64 2008

683.426dc22

2008025755

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

Learning to Shoot

Shotgun Etiquette

The Pump-Action Gun

Why a Two-Barreled Gun

The Modern Autoloader

The Case for the Small Gauge

How to Make Your Gun Fit

Cross Firing

Recoil and Balance

Triggers, Flinches, and Lock Time

Barrels, Chokes, and Forcing Cones

Choosing Chokes and Loads

Shot in the Dark

Effects of Wind and Weather upon Shotshell Performance

Velocity and Penetration

Stock Answers

How Good Is Your Duck Load?

Forward Allowance

The Fine Art of Waterfowl Shooting

Upland Gunning

Trap and Skeet

Competition

The Shot String Story

The Future Looks Harder but Brighter

FOREWORD

In 1956, a game warden friend of mine mentioned that the new outdoors editor of the Houston Chronicle , whod just moved to the city from the piney woods of East Texas, was one of the best field shots hed ever seen, and with a little coaching might make a champion at trap or skeet.

I promised Id help the young man any way I could.

At the Oleander Skeet Championships at Galveston that year there was a special 50-target event for sportswriters covering the shoot, and Bob Brister showed up lateI expect on purpose. It was obvious he had never seen a skeet field and didnt even know which house the bird came from. I think for fear of being embarrassed, he didnt even bring a gun.

I introduced myself, handed him my old Model 12 and told him those targets were a whole lot easier to hit than doves or ducks. His first shot went off almost before the bird got out of the house. Id forgotten to tell him my trigger had been honed down to a very light pull, and it went off before he was ready.

But he smoked the next target, and from then on all I had to do was stand behind him and tell him how far to lead the bird. He broke the next 49 straight and won the trophy.

What Brister could have done in clay-target shooting, if hed ever gotten really serious about it, nobody knows. But his heart was in hunting, and also about that time live-pigeon shooting got started along the Mexican border and with his field-shooting experience he was a natural.

I dont know how many times hes made the All-American TAPA pigeon team, and Ive watched him take trophies at trap, skeet, box bird shoots, columbaire shoots, the Southwest Quail Shooting Championship, and just about anything thats done with a shotgun. We used to have an annual powder pigeon championship in Houston, a clay-target game similar to crazy quail, and Brister either won or placed in it every year. When our Greater Houston Gun Club installed an international trap field, he broke 100 straight, practicing for the final U.S. team tryouts, which is the only straight anybody ever shot on our international field.

In the 20 years Ive hunted with him and shot competition with him, no matter whether the game was geese or clay pigeons, I could always count on two things: Brister would be hard to beat and he would also be changing guns, swapping stocks, testing loads, or experimenting with something the whole time.

I remember one big pigeon shoot; he was wood rasping the comb of his gun to make it shoot lower and somebody asked how many birds hed missed to be hacking on such a beautiful new gun. He hadnt missed any, but said he didnt like the way he hit em, that he was shooting high. The next day he won the championship and was right in the middle of every bird.

When I heard some of our gun club members talking about a 16-foot-long moving target used for studying shot strings, I didnt even ask who it belonged to. Who else would go to the trouble of changing a 16-foot-long piece of paper after every pattern? But Brister has an inquiring mind that just doesnt run down.

If anyone is capable of writing this book, I believe he is. Hes one writer who has lived what he writes about. And if there is anything he hasnt tried with a shotgun, I dont know what it is.

GRANT ILSENG

Houston, Texas

PREFACE

It has been written that shotgunning is a slapdash sort of thing, its use more an art than a science. Indeed the vague public conception of the scattergun is just thatpellets so scattered about that far less skill is required than with a rifle. Yet watching a bearded, muscled young man named Dan Bonillas, deep in concentration, relentlessly smoking fast-moving clay targets shot after shot, hundred after hundred, with the small, tight pattern of a full choke, it becomes obvious that there is also precision to the shotgun.

Each time the gun is opened, smoke curls up from cartridges evolved after years of research into the chemistries of powder and plastics, each shot a controlled explosion, firing within milliseconds of the ignition period of the one before it, and that is only part of the science of the shotgun.

An old master respectfully shoulders a fine double, and it becomes a living thing of grace and fluid motion, reading the myriad variables of angle, speed, and directional changes of birds in the wind to literally paint them from the sky. And that is the art of the shotgunthe most popular firearm in use in America.

As human populations increase, and big-game species become harder pressed for habitat, the use of the smoothbore will become more significant to the sport of hunting and thus to the continuance of the rights of Americans to own and use firearms. The majority of Americans now working hardest to uphold those rights are hunters.

The book is written out of respect for the shotgun and toward a clearer understanding of how it can be more efficiently used for the good of the game, the hunter, and the shooting sports.

Since I am neither artist, scientist, ballistician, nor even a very good nitpicker, no claim is made that my tests of patterns, performance, or shooting methods are to be taken as gospel. For acceptable statistical validity, thousands more tests would have to be run, requiring years for an individual to accomplish.

What we have here are indications , one mans attempt to find out new things about a very old firearm. The most significant findings would seem to be the addition of a new dimension to consideration of the shot string and what it means to clean-killing effectiveness with modern loads. In this respect, I am indebted to the counsel and assistance of many authorities, some shooters and some who work within the industries that produce the guns and ammunition. I have tried to be more reporter than investigator, although it is impossible to be one without the other.