DISCLAIMER

The world of meat butchery is very large and varied. While weve taken care to represent the most common cuts and types of meat, the author and publisher cannot guarantee that this guide addresses every possible type of meat available worldwide.

Copyright 2005 by Aliza Green

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Number: 2004103016

eBook ISBN: 978-1-59474-846-2

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978-1-59474-017-6

Print design by Karen Onorato

Photographs by Steve Legato

Illustrations and Iconography by Karen Onorato

Edited by Erin Slonaker

All photographs copyright 2005 by Quirk Productions, Inc.

Quirk Books

215 Church Street

Philadelphia, PA 19106

quirkbooks.com

Contents

Icon Key

Introduction

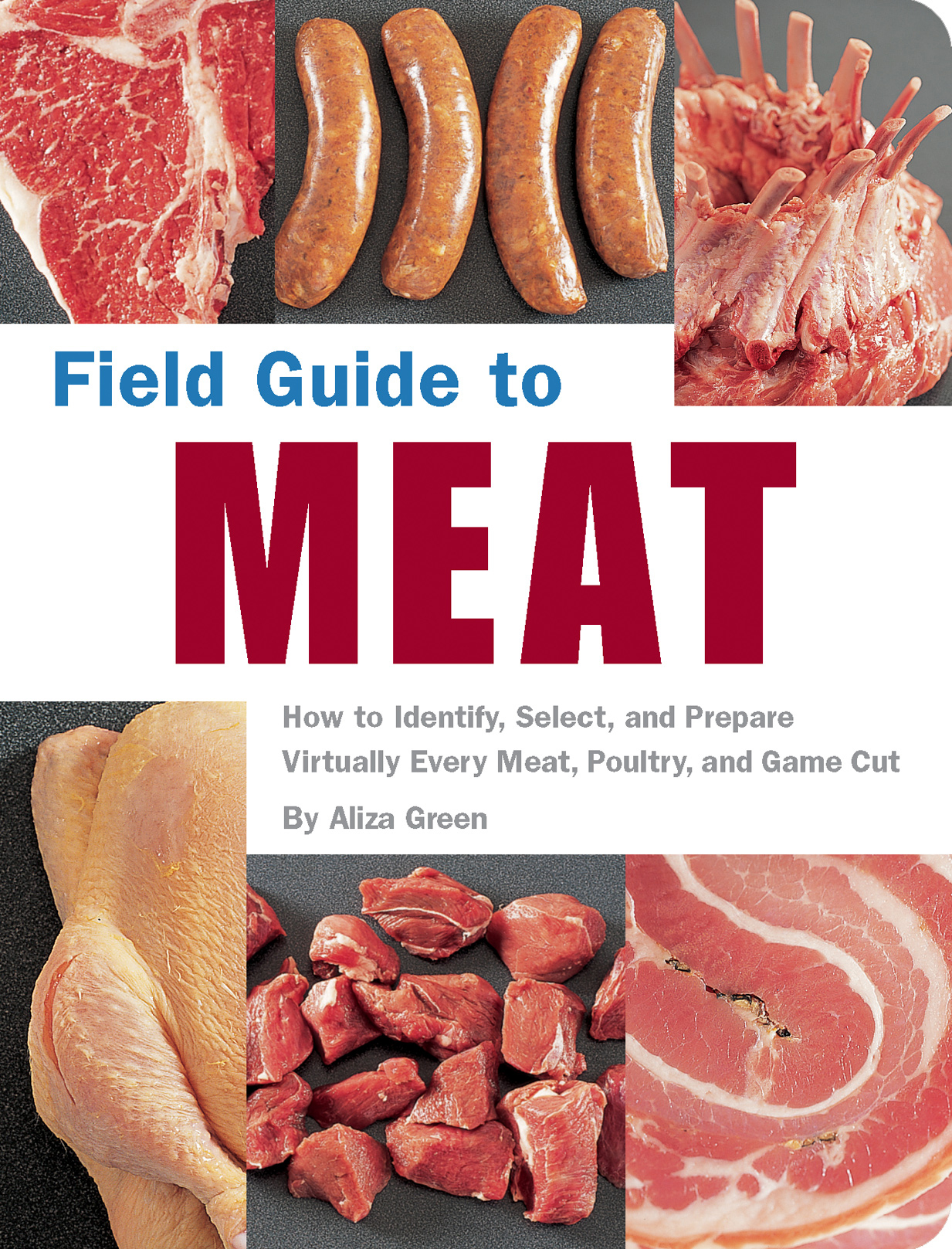

Heres a compact, easy-to-carry book packed with information and photos to help you sort your way through the meat counters offerings. It includes everything you need to know about identifying, choosing, storing, and preparing everything from common meats like beef, pork, veal, and lamb to unusual ones like goat, wild boar, and bison, along with poultry, game, cured meats and an assortment of sausages, from andouille to zungenwurst.

For professionals, the book includes the North American Meat Producers ( NAMP ) cut numbers and names. To make international cooking easier, Ive included equivalent names in French, Spanish, Italian, British, and other languages along with many regional and colloquial names.

You will learn about London broil (marinated grilled flank steak from London), guinea fowl (a close cousin to the chicken and pheasant that tastes deliciously of both), and chorizo (Spanish and Latin American spicy pork sausage). Detailed preparation instructions and food affinities make it easy to explore new cuts and meats. Turn to the photo section to help identify your cut.

To write this book, I called on my 30 years of hands-on experience working with meats as chef, mother (and home cook), food writer, and teacher as well as conducted extensive research. While it would take a book the size of a full-grown steer to cover all the meat sold in todays ever-changing food market, I have crammed as much information about as many types of meat as possible into this little book.

Im happy to hear from readers, with comments, questions or suggestions. Send me an e-mail at www.alizagreen.com and Ill do my best to reply quickly.

Aliza Green

I. Beef

Beef is the meat of domestic cattle ( Bos taurus ) and belongs to the Bovidae family. Modern domestic cattle evolved about 8,500 years ago from the wild aurochs, which died out as late as the early seventeenth century in Poland. Cattle is a broad term that includes beef, humped cattle, water buffalo, bison, and yak. Beef is eaten mainly in Northern Europe, North and South America, and Australia. Americans eat about 60 pounds (27 kg) a year per person compared with the Chinese at only 6 pounds (2.7 kg). Argentineans eat as much as 80 pounds (36 kg) annually.

Purebred cattle breeds have been selectively bred to possess a distinct identity and the propensity to pass these traits to their offspring. Beef usually comes from castrated males or steers slaughtered at 18 to 24 months of age. All beef cattle start out eating grass; in the United States three-fourths are finished (grown to maturity) in feedlots where they are fed mostly corn, while the remaining quarter are fed only grass. Beef in South America and Australia is generally grass (or pasture) fed. Corn-fed beef is richer and milder in flavor; grass-fed beef is leaner and stronger in flavor. Worldwide, antibiotics are used to treat sick animals but are prohibited as growth promoters. In the United States, hormones may be used to promote efficient growth.

Look for beef with a minimum of creamy outer fat. The bones should be soft looking with a reddish color; the meat is best when firm, fine-textured, and light cherry-red. Avoid meat with yellowish or gray fat, little to no marbling, two-toned color, or an unpleasant odor.

The U.S. government conducts stringent mandatory inspections of both live animals and carcasses. All fresh and processed meat products shipped from one state to another must be stamped Inspected and Passed by the Department of Agriculture. However, the stamp indicates safety only, not quality or grade.

Grading is voluntary and is based on the amount and distribution of marbling (the white flecks of fat) within the muscles. The greater the marbling, the higher the grade, because marbling makes beef more tender, flavorful, and juicy. (The protein, vitamin, and mineral content are similar regardless of grade.) Much of todays supermarket meat is choice, the most popular grade. Select is the lowest retail grade and is the leanest, therefore it can be tough. Lower grades are not found at retail; they are ground or used in processed meats. Only about 2 percent of beef is graded prime (advertisements for prime rib are likely for choice beef rib). Prime beef is high priced and found in high-end butcher shops and fine restaurants. Because the entire animal receives the same grade, less expensive cuts and variety meats of prime-graded steers may be worth seeking out.

A special, much-prized type of beef, Kobe beef, comes from Wagyu cattle, which are genetically predisposed to intense marbling. In Japan, they are fed sake mash and beer and are sometimes massaged with sake, producing meat that is extraordinarily tender, finely marbled, and full-flavored. Kobe beef graded A5 in Japan is 20 to 25 percent fat; U.S. and Canadian prime beef is 6 to 8 percent fat. When cooking Kobe beef, sear it quickly so that it blackens on the surface but remains rare. The meat is smooth, velvety, and incomparably sweet, with a subtle tang that lingers on the palate. Kobe beef is usually sold frozen but does not suffer in texture or flavor.

About 90 percent of American beef is shipped as boxed beef (wholesale cuts that are vacuum-packed and boxed for shipping). The retailer refrigerates boxed beef until needed for sale, when the bag is opened and the meat cut. During the period the meat is in the bag, averaging about seven days, it ages. This is referred to as aging in the bag or wet-aging.

Dry-aging is an old-fashioned, expensive, and slow process still done by top butcher shops and restaurant purveyors. Beef is dry-aged anywhere from ten days to six weeks to develop additional tenderness and flavor using controlled temperatures and humidity. The longer the aging, the more the benefits but also the more shrinkage and trimming. The length of time and method of aging is a personal preference. Dry-aging results in a unique flavor that may be described as musty; aficionados love this flavor, calling it gamy or intense. The tenderizing effects of aging are more evident in older animals. Beef that is not aged at all can be metallic tasting and lacking beefy flavor.

In the early twenty-first century, Mad Cow Disease became a concern for most beef consumers. Mad Cow Disease is the common name for bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), a progressive, degenerative, and fatal disease affecting the central nervous system of adult cattle. BSE is not destroyed by cooking. Research indicates that organ meat, rather than muscle meat, is the source of infectious prions (the diseased proteins). Limit risk by avoiding head and spinal meat and processed beef products that may contain nervous-system tissue, such as hot dogs, sausage, and ground beef. Organic and 100 percent grass-fed beef carry the least risk, since these cattle are not fed any animal products. Small producers are now selling grass-fed beef directly to restaurants and at farmers markets. Kosher and Halal meat also carries less risk because it is forbidden to use animals that are ill or injured, and the hand-slaughtering method ensures that brain matter does not contaminate the meat.