Watch and see what happens

from Raoul Moats Facebook page

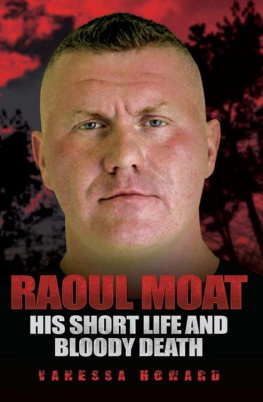

W hen the end came, it seemed inevitable. How else could it end?

The figure was picked out in green using night-vision technology; he was lying on soaking wet grass as police dogs barked and officers shouted out into the darkness. The tension between those on the ground had been stretched out over six hours. Perhaps Britains most wanted man knew that this was the moment; one firm squeeze of the trigger and it would be all over.

Even amongst those who hadnt followed the 24-hour news coverage, few would be surprised to wake on the morning of Saturday 10 July to hear that Raoul Moat had been shot and killed. He had been cornered on the side of the river bank in the now infamous town of Rothbury since seven oclock on Friday evening. He had finally been surrounded by snipers as part of the police operation, the scale of which was almost unprecedented.

In the days leading up to these final moments, the public had learned more details about the resources that had been used to find Moat. Hundreds of officers from 15 police forces had been recruited for the hunt, specialist advice had been sought from the British Army, the Police National Search Centre, and even the heat-seeking technology of a 20m RAF Tornado jet had been employed. The final cost of the operation would mount to more than three million pounds. All to track one man.

There were those who thought the use of so much firepower was risible, news that armoured vehicles from Northern Ireland had arrived to patrol the quiet streets of Rothbury was remarked on as excessive. Yet when Moat went on the run, it was only four weeks after Derrick Bird had shot dead 12 people and injured 11 more in and around the quiet country lanes of Cumbria. How else could Northumbria Police have been expected to respond?

A madman was on the loose, a self-declared maniac; a man who had killed one man, seriously injured his former partner, and shot a police officer in the face. He had declared war on the police and, as the days of his week-long evasion unfolded, he threatened to shoot members of the public. The rules had changed he had warned in a taped message left for the police to find. The hunted had become the hunter. The authorities were under no illusion as to what Moat was capable of and he had made his intentions clear in a letter that he had handed to a friend in which he had stated: I wont stop till Im dead.

How had it come to this? What had driven one man to cause such terrible suffering to the families of his victims? Had he suffered a catastrophic breakdown or had the signs of his collapse been evident for years to all who had encountered him? What had turned a loving father into a monster, a man who would declare war on the police?

Perhaps this was no more than a freak event, something so rare as to offer little insight into what can destabilise an ordinary man.

Yet the truth, even as it emerges in a fractured and partial way, suggests something that has far-reaching and even terrifying implications. All the signs were there: this was a man who had already brought misery to the lives of others, a person who had known years of destructive rages and yet was also someone who had asked for help.

He knew that he suffered from what he described as areas of fault, dark parts of his psyche that he feared: rages that surfaced in him and that he could not control.

The youngster in the baby pictures, the plump-faced and bright-eyed boy, would would become a killer, a man his mother would no longer recognise. Step by step, he walked a path of destruction and no one helped him find another way. He wanted help. None came, or at least, if and when it did it was too little and too late. Now he would ensure that everyone would pay, that the whole world would learn his name and there was only one way it would end.

We know the name yet do we know other Raoul Moats? Other men in other communities waiting for the killer inside them to emerge and take control. For Moat is no one-off, his was not a isolated act of revenge. Other people whose thinking mirrors his are out there.

This book will reveal how disturbed minds such as Moats are formed and how, as a society, we need to understand why Moat is now an antihero to many. There is a dark undercurrent of disaffection that, should it settle in the mind of someone battling instability and grievances, can yield terrifying results.

THURSDAY 1 JULY

Most of what Ive done Ive gotten away with, no arrest.

from Raoul Moats letters

T hose whove been incarcerated behind HM Prison Durhams bleak and imposing walls may well be amused to learn that its architect was imprisoned as it was being built for theft of the funds intended for its construction.

Perhaps it was not an auspicious start for a building that has housed some of Britains most infamous hard men criminals over the last two hundred years, names like John McVicar, Frankie Fraser, Ronnie and Reggie Kray. As well as men with a reputation for violence, Durham has housed female serial killers such as the arsenic poisoner Mary Ann Cotton. It is believed that she was responsible for the deaths of 21 victims and she was hanged at the gaol in 1873. More recently, the prison inmates have included Rose West and Myra Hindley.

Yet its notorious reputation perhaps belies the fact that it is no longer a Category A prison but a Category B. Once it held the countrys most violent and highly dangerous inmates but, with its downgrade, it now acts as a local prison for convicted and remand adult male prisoners, primarily serving the courts of County Durham, Tyne and Wear and Teesside. Men who the authorities decide do not require maximum security and who often serve short-term sentences. Men like Raoul Thomas Moat.

Despite its harsh appearance, HM Prison Durham has been undergoing a substantial re-fit over the last ten years and is perhaps better equipped than ever to deal with its migrating population. When the prison hit the headlines seven years ago because figures were released showing it had the highest suicide rate of any English gaol, refurbishment may well have been overdue. Coping with the often complex social and psychological needs of prisoners is far from straightforward. Many have known years of alcohol or drug abuse or both, and many more grew up in dysfunctional households or spent periods of time in care. A lack of consistent and nurturing parental attention leaves many young men ill-prepared to deal with stress, often meaning that they resort to violence when needs are not met or if a threat, real or imagined, is identified.

On top of these psychological problems, some of the prisoner population also face practical difficulties. It is thought that anywhere between a third to two-thirds of prisoners are functionally illiterate and the effect of the failure to rehabilitate prisoners has led the Howard League for Penal Reform to report that two-thirds can be expected to re-offend within two years.

Prison, then, can be a fraught environment. Whilst there are those who take responsibility for their actions and see a custodial sentence as an opportunity to change their behaviour, they remain in the minority. Help is on hand: literacy tuition, courses in woodwork, bricklaying, painting and decorating and even, with a nod to the twenty-first century, Data Inputting. Giving a structure and direction to inmates time is important but with shorter sentences, there is no simple route to rehabilitation. There is no magic wand.

A man like Raoul Moat will not have cut a remarkable figure walking the halls and walkways of Durham. True, he was tall and physically imposing at 6ft 3in and had the physique of someone who was committed to body building; yet even impressive physical attributes are not uncommon amongst those who are convicted. The gym is perhaps the busiest section of any prison and body building is a common obsession for men inside. It is easy to guess its attractions: whilst gaining bulk, men radiate the signal that they are not to be messed with, and even those who are incarcerated for the first time will seek to present an image of themselves as untouchable once behind bars. Besides, boredom is the main and overriding factor in any jail term. It is not unheard of for prisoners to spend 18 hours locked in their cells and working out is a simple distraction.

![Hankinson Andrew - You Could Do Something Amazing with Your Life [You Are Raoul Moat]](/uploads/posts/book/208553/thumbs/hankinson-andrew-you-could-do-something-amazing.jpg)