FOR MY MOTHER AND FATHER, WITH LOVE

CONTENTS

ix

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Anyone who writes about the history of New York City feels a kinship with the immigrant at Ellis Island, faced with a bewildering array of information, impressions, and leads, grateful fir the help of colleagues, friends and passers-by. It is a pleasure to thank those who have aided me in the long project of researching, writing and producing this book.

My oldest debt is to Mari Jo Buhle, who guided this research as a dissertation; the conceptualization of the book, its organization and prose have benefited immeasurably from her careful readings of drafts and meaningful suggestions, while her friendship and belief in my work have sustained me for a number of years. I am obliged as well to another graduate school mentor, Howard Chudacoff, for his useful questions, intelligent criticisms, and unwavering support. Susan Porter Benson and Roy Rosenzweig read this manuscript in painstaking detail, and incalculably helped me to chart revisions. I am very grateful to Linda Shopes, for her insightful advice on several chapters; Judith Gerson, who sharpened my thinking about gender; David Green, who thoughtfully commented on many drafts; and Robert Earickson, for his help on countless details. These friends have also suffered through this work with me at various times, and offered their comradeship and good humor in what has often been a lonely task.

My work has benefited significantly from discussions with various scholars at different conferences and seminars; while our meetings have often been brief, they have given me much to ponder. Lewis Erenberg, Stephen Hardy, Daniel Horowitz, Dale Light, and Priscilla Murolo in particular made very helpful comments on various parts of this work. Lois Banner and her NEII Summer Seminar for College Teachers in 1984 offered many useful suggestions, as did participants in my women's history study group, JoAnn Argersinger, Toby Ditz, Elizabeth Ermarth, Jenny Jochens, Marylynn Salmon, Linda Shopes, and Karen Whitman.

I could not have undertaken this project without the superb collections of the New York Public Library. The staff of the Rare Books and Manuscript Division, especially Richard Salvato, gave me creative advice on sources and extensive help in a project whose boundaries were broadly defined. I am particularly grateful to William Joyce and Robert Giroux for granting inc permission to examine the papers of the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures. The New York Public Library's staff in the Local History and Genealogy Division, and the Theater and Dance Collections at the Lincoln Center Library of the Performing Arts were unfailingly helpful. I am also indebted to librarians and archivists at the following libraries: Tamiment Institute Library, New York University; the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University; the Archives of the National Board of the Young Women's Christian Association of the U.S.A.; Laura Parsons Pratt Research Center of the YWCA of the City of New York; U. S. National Archives; City University of New York; Brown University; and University of Maryland Baltimore County. At U M BC, Tom Beck gave the expert help in finding photographs, and Cartographic Services skillfully and quickly drew the maps.

I have been fortunate to receive several research grants which allowed me time for uninterrupted work. A National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Stipend, Woodrow Wilson Foundation Predoctoral Fellowship in Women's Studies, and two University of Maryland Baltimore County Summer Faculty Fellowships have given me much needed support. My colleagues in the American Studies Department and the Dean of the Faculty at UMBC graciously gave me released time in order to complete the book.

The professionalism and enthusiasm of the staff at Temple University Press have enhanced the process of turning the manuscript into a book. I have been most fortunate to work with Janet Francen- dese, an editor whose infectious cheer and clear-headed advice have brought me out of writer's doldrums on several occasions. I am obliged as well to Candice Hawley, the production editor, and the many individuals who contributed to the production and distribution of the book.

Finally, thanks go to my parents, Clarence and Evelyn Peiss, whose wit, curiosity and passion for knowledge have irresistibly marked their daughter's life and work. This hook is dedicated to them.

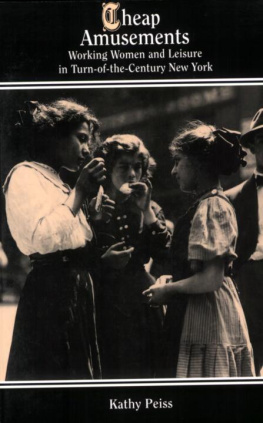

CHEAP AMUSEMENTS

INTRODUCTION

Just now her search is translated very lightly and gaily into the demand for "a good time" and a keen interest in the other sex. I

I was a lively girl, a devil, I was healthy, young and all that, and they used to say I was very pretty also, and I was all over, you know, I wasn't sleeping like other girls.2

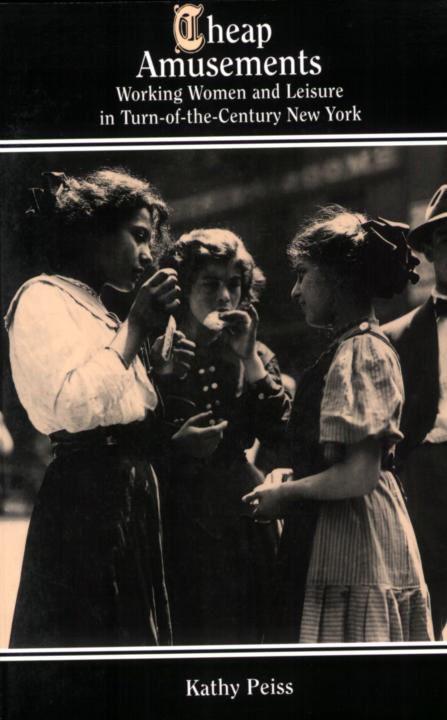

This book is a study of young working women's culture in turn-ofthe-century New York City-the customs, values, public styles, and ritualized interactions-expressed in leisure time. Wandering through the dance halls, streets, nickelodeons, and amusement parks of the metropolis, I explore the trivia of social experience for cities to the ways working women constructed and gave meaning to their lives in the period from 1880 to 1920. Until recently, the historical record silenced those who left few written accounts and committed no "great" deeds. The flowering of feminist scholarship has at last begun to restore working-class women to history, establishing the significance of their activities in the household, workplace, and political arena. But leisure?-a minor pursuit, if' not an outright contradiction; as one Polish immigrant remarked, "Who had leisure time?";

Nonetheless, many working women carved out of daily life a sphere of pleasure that belied the harsh realities of the shop floor and tenement. Their activities, moreover, offer a window into social practices often obscured in other areas of human experience, opening to view the central concern of this hook, the cultural handling of gender among working-class people. Public halls, picnic grounds, pleasure clubs, and street corners were social spaces in which gender relations were "played out," where notions of sexuality, courtship, male power, female dependency, and autonomy were expressed and legitimated.

At the same time, leisure is not simply a vessel whose contents reveal a unified culture, nor is its relationship to other spheres of life such as work and family one-dimensional. Leisure activities may affirm the cultural patterns embedded in other institutions, but they may also offer an arena for the articulation of different values and behaviors. The working-class construction of gender was influenced by the changing organization and meaning of leisure itself, particularly the effects of ongoing capitalist development on the organization of work and time, and the intensive commercialization of leisure in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.