Throughout the 20th century, various labels have been applied to students who were considered the hard-to-teach, the hard-to-reach, and the least privileged (Allington, 1994, p. 97). Whether they have disabilities, are at-risk, are low achieving, have limited English proficiency, or are marginalized for some other reason, they have traditionally been placed in.

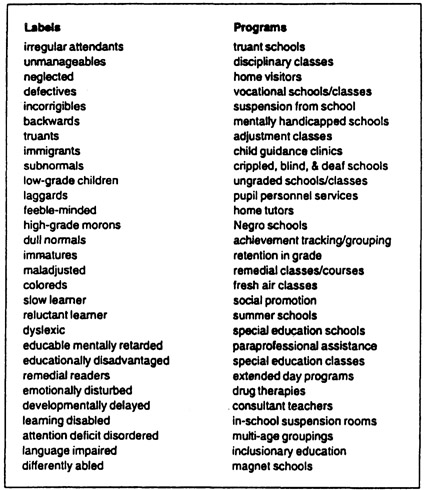

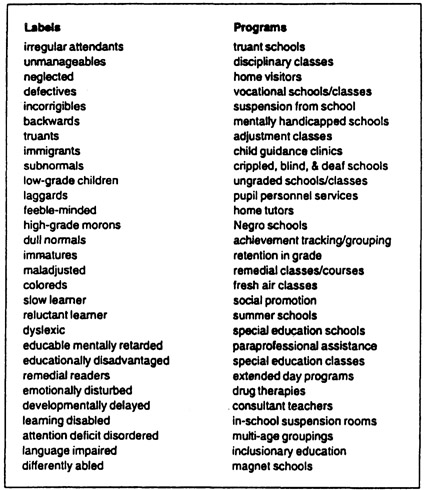

Labels and programs for marginalized students in American elementary schools, 1900-2000 (Ailing ton, 1994, p. 99; reprinted with the permission of Richard Ailing ton and the National Reading Conference.)

In response to federal legislation and court rulings, these labels and programs have changed over time and grown in number. The most important federal legislation affecting special education was the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, known as Public Law 94-142, renamed the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, (PL 101-476) in 1990). Originally passed by Congress in 1975, the purpose of IDEA was to provide equal educational opportunity and access to the public schools for students with disabilities. In addition to mandating that students with disabilities have access to a free, appropriate public education, IDEA also established the concept of the least restrictive environment (LRE). The intent of LRE is to educate students with disabilities along with their nondisabled peers to the maximum extent appropriate, and for special classes, separate schooling, or other removal of students with disabilities to occur only when the nature of the severity of the disability is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aid and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily (IDEA, 1990, p. 169). Although LRE has often been confused with mainstreaming, these terms should not be used interchangeably (Osborne & DiMattia, 1994). Whereas LRE refers to a range of possible placements, with a preference for general education settings, mainstreaming refers to the practice of placing students with disabilities in the general education classroom, which is only one of the options available in LRE. However, to many educators mainstreaming has become associated with cost-cutting measures in which students with disabilities are placed in general education classes without the necessary additional supports and services (see Hardman, Drew, & Egan, 1996).

Since IDEA went into effect in 1976, special education has grown enormously. In 1994/1995, for example, more than 5.2 million children (10% of all students enrolled in school) were receiving special education services (U.S. Department of Education, 1997). Tens of thousands of additional special educators have been hired, representing 13% of all teachers in the United States in 1990 (Fuchs & Fuchs, 1994). Not surprisingly, state-reported expenditures for special education have also grown enormously. For example, $18.6 billion was spent on special education and related services in 1989/1990 (Chaikind, Danielson, & Brauen, 1993).

As the number of students in special education has grown, so have the different kinds of specialized programs in segregated settings and the special education personnel to staff them (Allington, 1994). Critics of LRE (see Lipsky & Gartner, 1996; Taylor, 1988) have argued that, although LRE states a preference for the education of students with disabilities in regular education settings, it legitimates segregated, restrictive environments. Taylor (1988) argued that defining LRE operationally in terms of a continuum of educational placements, ranging from the most restrictive environment to the least, suggests that the most restrictive setting, such as an institution or special school, would be appropriate under some circumstances. Further, according to Taylor, the continuum of placements confuses the physical setting with intensity of services; that is, it assumes that the most restrictive and segregated placements offer the most intensive services, whereas the least restrictive and integrated settings provide the least intensive services. Yet, as critics note, intensive services can be provided in integrated settings, and some of the most segregated settings have provided the least effective services. Another criticism is that LRE is based on the readiness model, which assumes that people must acquire certain skills and thus earn the right to move to the least restrictive setting. However, critics argue that restrictive environments do not prepare people for more integrated settings. Yet another criticism is that the criteria for assigning labels and determining placements are ambiguous, vary widely, and are influenced by issues of race, class, and gender, as well as funding considerations.

The percentage of students who are classified as needing special education varies enormously from state to state. Based on an analysis of Department of Education data, U.S. News & World Report (Shapiro, Loeb, & Bowermaster, 1993) reported that 15% of students in Massachusetts were labeled as special needs students compared to only 7% in Hawaii and 8% in Georgia and Michigan. In Alabama, 28% of special education students were classified as mentally retarded, compared to 3% in Alaska. Furthermore, a disproportionate number of special education students were from minority groups. For example, African-American students were two to three times as likely as White students to be classified as mentally retarded; when White students were classified, they tended to be given the less stigmatizing label of learning disabled (LD). Wide discrepancies also occurred among states in their labeling of African-American students: Whereas five states (Alabama, Ohio, Arkansas, Indiana, and Georgia) labeled 36% to 47% of their African-American students in special education as mentally retarded, five other states classified less than 10% of such students as mentally retarded (Nevada, Connecticut, Maryland, New Jersey, and Alaska).

According to statistics from the Report of the American Association of University Women (AAUW, report 1992), far more boys than girls are referred to special education, although medical reports indicate that disabilities occur almost equally in boys and girls. Furthermore, girls who are identified as LD have lower IQs than boys labeled as LD, suggesting that boys are overreferred. Socioeconomic status (SES) also plays a role in referrals to special education, although it is a complicated one. Teachers who perceive themselves as ineffectual are far more likely to refer lower SES children with mild learning problems to special education than similar children from higher SES families (Podell & Soodak, 1993).

According to Allington (1994), classification has more to do with lack of early literacy experience than with innate ability: The most direct route to being identified as at risk or handicapped in schools today is to arrive at school with few experiences with books, stories, or print and then exhibit any sort of difficulty with the standard literacy curriculum (p. 95). Others argue that labels and segregated settings are designed to serve the needs of schools and societynot studentsby attributing the problem of school failure to deficiencies in students, their parents, or their culture, rather than to inappropriate educational programs or practices (McDermott & Varenne, 1995; Skrtic, 1991). A related concern is that decisions regarding classification and placement are highly influenced by funding patterns rather than clinical evidence or objective judgments (Kliewer & Biklen, 1996).