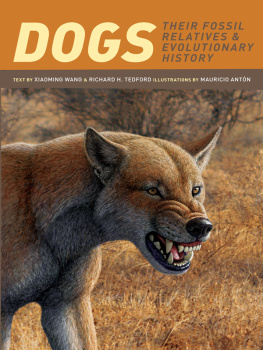

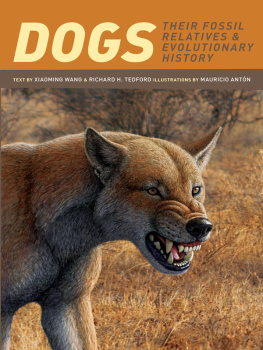

DOGS

DOGS | THEIR FOSSIL RELATIVES AND EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY |

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

XIAOMING WANG + RICHARD H. TEDFORD | MAURICIO ANTN

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2008 Columbia University Press

Illustrations copyright 2008 Mauricio Antn

Paperback edition, 2010

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-50943-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wang, Xiaoming, 1957

Dogs : their fossil relatives and evolutionary history / Xiaoming Wang and Richard H. Tedford ; illustrations by Mauricio Antn.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-13528-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-13529-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-50943-5 (e-book)

1. Dogs. 2. Canis, Fossil. 3. DogsEvolution.

I. Tedford, Richard H. II. Antn, Mauricio. III. Title.

QL737.C22W36 2008

599.772DC22

2007052328

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

BOOK DESIGN by VIN DANG + JACKET DESIGN by MARTIN HINZE

CONTENTS

THE LONG ASSOCIATION OF HUMANS and the domestic dog has attracted considerable interest in the biology and natural history of the Canidae (dog family), among both specialists and the general public. Several recent events have converged to inspire further interest in canids. New discoveries of early domestic dogs living in Israel and Germany more than 14,000 years ago push back the fossil record and provide tantalizing evidence of initial interactions between early humans and their first domestic animal. Meanwhile, molecular studies indicate that China, not Europe or the Middle East, may have been the center of first domestication. Moreover, humans fascination with large predators such as wolves and hunting dogs has continued to draw public attention to a variety of issues ranging from predatory behavior to ecology and conservation. The conservation and reintroduction of gray wolves in Europe and North America and of red wolves in the southeastern United States have promoted public debate regarding the need to protect large predators in order to achieve a balanced ecological community.

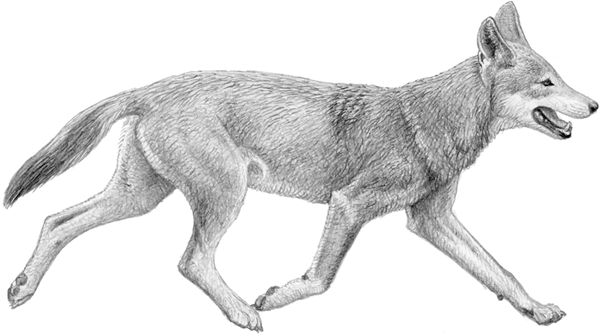

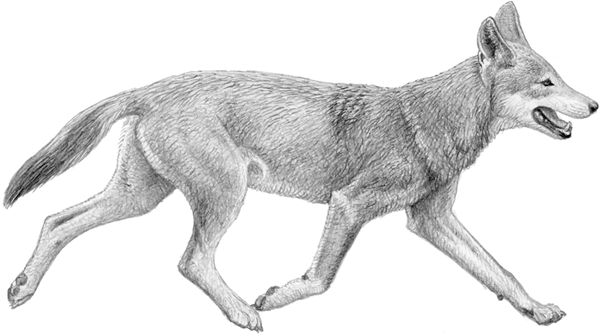

Against this background of sustained public interest in everything about dogs, the unparalleled Frick Collection (American Museum of Natural History) of North American Cenozoic canids has been the subject of three monographs by Xiaoming Wang (curator of Vertebrate Paleontology), Richard Tedford (curator emeritus of Vertebrate Paleontology), and Beryl Taylor (curator of the Frick Collection) (Wang 1994; Wang, Tedford, and Taylor 1999; Tedford, Wang, and Taylor in press). The wealth of information provided in these monographs reveals a vast array of extinct canids in North America, the continent of their origin, and their subsequent expansion to the Old World about 5 to 7 million years ago (Ma) and to South America around 3 Ma. These immigration events ultimately helped to make canids one of the most widely spread living carnivores in the world and the dominant predators on some continents. This book attempts to capture the excitement of recent advances in our understanding of the natural history of this family of carnivorans. The book is richly illustrated, both to provide an unprecedented visual reference for the specialists and to make it accessible and interesting to a wide nontechnical audience.

The family Canidae was the earliest group that still has extant members to arise within the order Carnivora. During their history of more than 40 million years, canids have also achieved a longevity and diversity unrivaled by any other group of carnivores. Their success is also exemplified by a worldwide distribution and achievement of top predator status in modern North and South America, Australia, and northern Eurasiaonly in Africa are they less dominant among large predators. It is argued that the propensity for canids to form large, social hunting groups and the associated development of their brain were crucially important in the domestication processhumans learned to form a mutually beneficial relationship with such an intelligent carnivoran that was preadapted to life among a different species. The importance of the domestication of various animals in early human societies cannot be overestimated, and it may have been first inspired by the domestication of dogs.

The evolutionary history of canids is a history of successive radiations (rapid expansions of diversity within a group of organisms, often in response to environmental changes or new resources) repeatedly occupying a broad spectrum of niches, ranging from large, pursuit predators to small omnivores and possibly even to herbivores. Three such radiations were first recognized by Richard Tedford (1978), each represented by a distinct subfamily. Two archaic subfamilies, Hesperocyoninae and Borophaginae, thrived in the middle to late Cenozoic from about 40 to 2 Ma. All extant canids belong to the final radiation, the subfamily Caninae, which achieved its present diversity only in the past few million years.

Previous diversities of canids were intimately related to environmental changes during the past 40 million years. Large, wolflike pursuit predators were in particular the direct consequence of the opening up of the landscape. A worldwide change from a warm and humid climate to an increasingly colder and drier climate resulted in large-scale transformation of forested environments to open grasslands worldwide. These changes were reflected in the terrestrial vertebrate community by an increasing cursoriality (the ability to run fast and for a long time) among predators and prey. This greater ability to run is clearly reflected in the fossil history of canids, which shows increasingly erect standing postures, progressively lengthened limb bones, and restricted movements of the joints.

Humans fascination with canids is derived from two main sources: our love affair with our dogs and our reverence of their top predator status in much of the world. Such a high interest in a group of mammals is generally rare and offers a great opportunity to engage the public in paleontology, functional morphology, evolution, and behavioral ecology.

WE THANK OUR PUBLISHERS at Columbia University Press, Patrick Fitzgerald and Robin Smith, and editor Irene Pavitt for their encouragement and helpful guidance. We are indebted to Lars Werdelin and Blaire Van Valkenburgh for their critical reviews, which brought to our attention records that we missed and other factual errors. A thorough editing by copyeditor Annie Barva has greatly improved the language and expression of this book. Alejandra Lora of the American Museum of Natural History typed part of the manuscript for publication and helped in numerous other ways to facilitate communications. A substantial part of the monographic treatments of the three subfamilies of canids were funded by two grants from the National Science Foundation (DEB-9420004 and DEB-9707555) and a Frick Postdoctoral Fellowship from the American Museum of Natural History. Xiaoming Wang thanks his wife, Yanping, and his son, Alex, for their support and understanding throughout the preparation of this book. Richard Tedford is grateful for the patience of Elizabeth and Vivien during the 30 years this study took to complete. Mauricio Antn thanks his wife, Puri, and his son, Miguel, for their patience during this long process.

Next page