Human evolution exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History, in New York.

HUMAN

EVOLUTION

Bernard Wood

STERLING and the distinctive Sterling logo are registered trademarks of

Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wood, Bernard A.

Human evolution: a brief insight / Bernard Wood.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-4027-7898-8

1. Human evolution. I. Title.

GN281.W67 2011

599.93'8--dc22

2010017328

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016

Published by arrangement with Oxford University Press, Inc.

2005 by Bernard Wood

Illustrated edition published in 2011 by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Additional text 2011 Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Distributed in Canada by Sterling Publishing

c/o Canadian Manda Group, 165 Dufferin Street

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M6K 3H6

Book design: Faceout Studio

Please see for image copyright information.

Printed in China

All rights reserved

Sterling ISBN 978-1-4027-7898-8

For information about custom editions, special sales, premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales Department at 800-805-5489 or specialsales@sterlingpublishing.com.

CONTENTS

Timeline of Thought and Science Relevant to

Human Origins and Evolution

FOR AN AUTHOR USED TO the luxury of lengthy academic papers and the occasional five-hundred-page monograph, and to the protection afforded by technical language and multiple qualifications, boiling down human evolutionary history to the size constraints and style of a Brief Insight was a considerable challenge. Thanks go to Mark Weiss for advice about genetics, to Matthew Goodrum, Ed Lee, and David Pilbeam for advice about the history of science and of human origins research, to my colleague, Robin Bernstein, to my OUP editor, Marsha Filion, and to an anonymous reviewer, for reading the entire manuscript and making valuable suggestions for revisions. Graduate students in the hominid paleobiology program at George Washington University, and Phillip Williams wittingly and unwittingly contributed by providing information and helping me find lost files and notes. I am grateful to several publishers for allowing me to adapt and use previously published images and figures. This book is for my family, young and old, and my teachers.

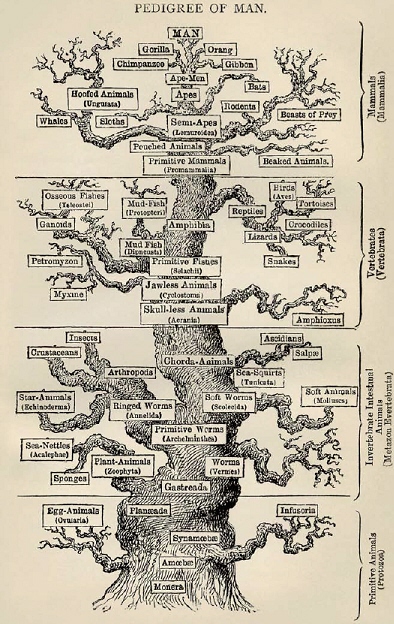

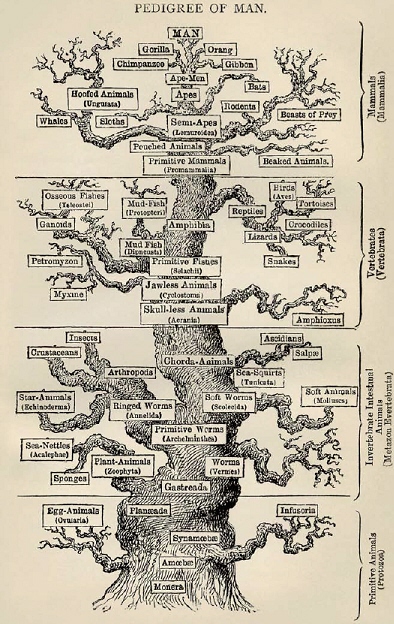

This early version of the tree of life is from German biologist Ernst Haeckels The Evolution of Man (1879).

MANY OF THE IMPORTANT ADVANCES made by biologists in the past 150 years can be reduced to a single metaphor. All living, or extant, organisms, that is, animals, plants, fungi, bacteria, viruses, are on the surface of an arborvitae, or Tree of Life, and all the types of organisms that lived in the past are situated somewhere on the branches and twigs within that same tree. The extinct organisms on the branches that connect us directly to the root of the tree are our ancestors. The rest, on branches that connect with our own, are closely related to modern humans, but they are not our ancestors.

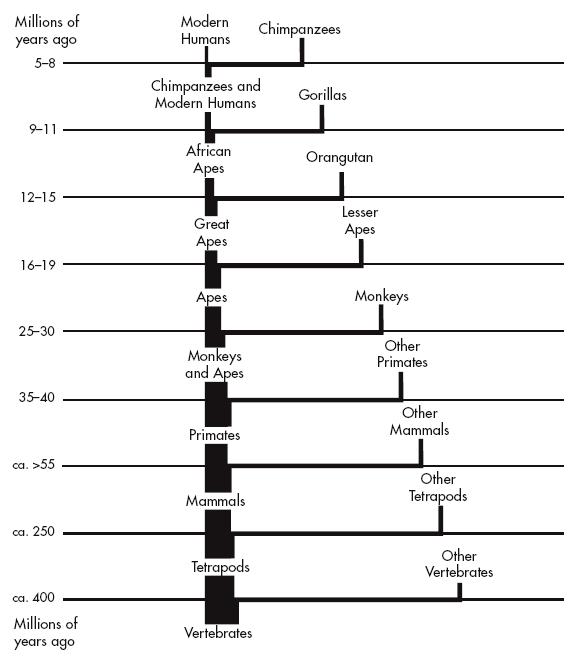

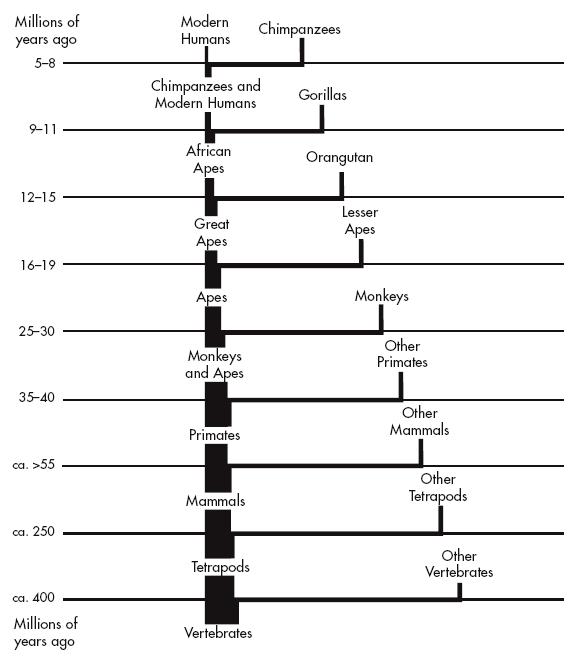

The long version of human evolution would be a journey that starts approximately 3 billion years ago at the base of the TOL with the simplest form of life. We would then pass up the base of the trunk and into the relatively small part of the tree that contains all animals, and on into the branch that contains all the animals with backbones. Around 400 million years ago we would enter the branch that contains vertebrates that have four limbs, then around 250 million years ago into the branch that contains the mammals, and then into a thin branch that contains one of the subgroups of mammals called the primates. At the base of this primate branch we are still at least 5060 million years away from the present day.

The next part of this long version of the human evolutionary journey takes us successively into the monkey and ape, the ape, and then the great ape branches of the Tree of Life. Sometime between 15 and 12 million years ago we move into the small branch that gave rise to contemporary modern humans and to the living African apes. Between 11 and 9 million years ago the branch for the gorillas split off to leave just a single slender branch consisting of the ancestors and extinct close relatives of chimpanzees and bonobos (chimps/bonobos) and modern humans. Around 8 to 5 million years ago this very small branch split into two twigs. At the root of the twigs is the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of chimps/bonobos and modern humans. One of the two twigs ends on the surface of the TOL with the living chimps/bonobos; the other also ends on the surface of the TOL, but with modern humans.

This book focuses on the last stage of the human evolutionary journey, the part between ourselves and the MRCA shared by chimpanzees/bonobos and modern humans. Paleoanthropology is the science that tries to reconstruct the evolutionary history of our small twig. It tries to find out how complex, or bushy, was the small, exclusively human, part of the TOL. But instead of referring to twigs we will use the proper biological term clade: extinct side branches are called subclades. Species anywhere on the clade that connects the MRCA with modern humans on the surface of the TOL are called hominins; the equivalent species on the clade that connects the MRCA with chimps/bonobos are called panins. And instead of writing out millions of years and millions of years ago (and the equivalents for thousands of years), we will use instead the abbreviations myr and mya and kyr and kya.

A diagram of the vertebrate part of the Tree of Life

emphasizing the branches that led to modern humans.

This introduction has three objectives. The first is to try to explain how paleoanthropologists go about the task of improving our understanding of human evolutionary history. The second is to convey a sense of what we think we know about human evolutionary history, and the third is to try to give a sense of where the major gaps in our knowledge are.

We use two main strategies to improve our understanding of human evolutionary history. The first is to obtain more data. You can get more data by finding more fossils, or by extracting more information from the existing fossil evidence. You can find more fossils from existing sites, or you can look for new sites. You can extract more information from the existing fossil record by using techniques such as laser scanning to make more precise observations about their external morphology. You can also gather information about the internal morphology and biochemistry of fossils. This ranges from using noninvasive imaging techniques such as computed tomography to obtain information about structures like the inner ear, to using a relatively new type of microscopy, confocal microscopy, to investigate the microscopic anatomy of teeth, and using the latest molecular biology technology to determine the structure of small amounts of DNA left in fossils.

Next page