Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following people who helped in the development of this book. Many people read all or sections of it, and helped to improve it: Debbie Guatelli-Steinberg, Henry Harpending, Katerina Harvati, Jim Kidder, John Relethford, Karen Rosenberg, Karen Schmidt, Liza Shapiro, Robin Smith, Shelley Smith, Christian Tryon, Christina Turner, Russell Tuttle, and Carol Ward. William McGrew was especially helpful in correcting errors and discussing the larger issues of human evolution with great enthusiasm. Nathan Brown of Blackwell Publishing should be especially thanked for his persistence and patience, both of which in their different ways were appreciated, and for allowing us to interpret his word urgent in our own idiosyncratic way. Fiona Sewell also provided much assistance in the production of the text and figures. R. F. would especially like to thank Marta Mirazn Lahr, for her tolerance of this distraction away from other things that were equally pressing, as well as, as always, endless expert advice and guidance.

PART 1

THE FRAMEWORK OF HUMAN EVOLUTION

PART 2

EARLY HOMININ EVOLUTION

PART 3

LATER HOMININ EVOLUTION

CHAPTER 1

THE GROWTH OF THE EVOLUTIONARY PERSPECTIVE

OUR PLACE IN NATURE

A s the train doors open at many stations on the London Underground, a disem-bodied voice can be heard saying Mind the gap to warn passengers that there is a larger than usual step between the train and the platform. This helpful announcement can act as a rather surprising motto for anyone about to embark on a course on human evolution.

KEY QUESTION How should evolutionary biology approach the problem of human uniqueness versus the continuities inherent in the evolutionary process?

The reason for this is very simple. If one asks the average person to come up with terms they associate with evolution, then after survival of the fittest, progress (of which more later), and missing link, another one that is highly likely to figure is continuity. Evolution is a continuous process, and so provides a link between all organisms in such a way as to place them all on a continuum, from the simplest single-cell organism to the most complex social mammal. Through evolution, plants and animals slide endlessly from one form to another. Continuity is therefore a major part of nature. However, the same average person, if asked whether there is a continuity between humans and other animals, is likely to answer no. Certainly there are many things that humans and other animals share, from their basic genetic code to the broad body plan of the vertebrate skeleton, but the gulf between humans and, say, chimpanzees, no matter how smart the latter appear to be, remains large, and to some unbridgeable. Humans are the species of Shakespeare and Dante, of Galileo and Einstein, of Wallace and Darwin, of Michelangelo and Picasso, of Beethoven and Bach; or alternatively, the species of Hitler and Stalin. No chimpanzee can come close to these sorts of achievements.

In the contrast between the continuity of evolution and the uniqueness of humans lies the challenge and interest of human evolution. It is the paradox that lies at the heart of the discipline how is it possible to simultaneously mind the gap that exists between humans and other species and be true to the continuous nature of the evolutionary process? It is that challenge that has fueled much of the research into human evolution.

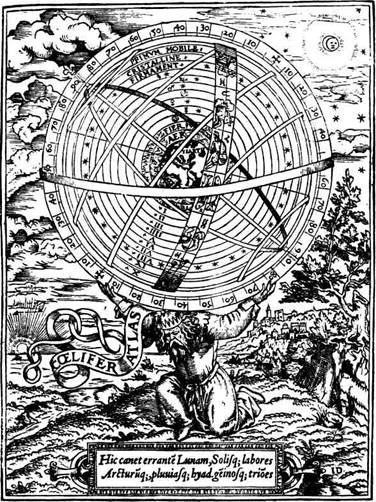

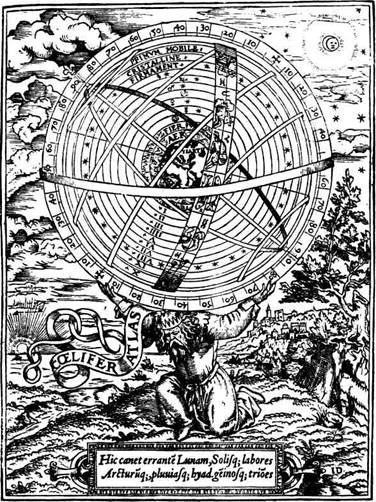

Ptolemys universe: Before the Copernican revolution in the sixteenth century, scholars views of the universe were based on the ideas of Aristotle as elaborated by Ptolemy. The Earth was seen as the center of the universe, with the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets fixed in concentric crystalline spheres circling it.

The problem of the gap has long been recognized. In 1859 Charles Darwin published his epoch-making book, The Origin of Species, in which he provided an account of how evolution worked, and how science might explain the patterns of life without recourse to supernatural beings and processes. While Darwin made little or no reference to humans, but confined himself to ordinary plants and animals, the implications were plain to see. Within four years his friend and supporter, Thomas Henry Huxley, published one of the first books on human evolution, Evidences as to Mans Place in Nature. The book was based on evidence from comparative anatomy among apes and humans, embryology, and fossils of early humans (few were available at the time). Huxleys conclusion that humans have a close evolutionary relationship with the great apes, particularly the African apes was a key element in a revolution in the history of Western philosophy: humans were to be seen as being a part of nature, no longer as apart from nature hence the title of Huxleys book. What both Darwin and Huxley, as well as many other scientists of that time, were keen to demonstrate was the continuity between humans and the rest of the biological world, and that all were the product of the same evolutionary processes. In other words, evolution underpinned the continuity of nature, including humans.1

Although Huxley was committed to the idea of the evolution of Homo sapiens from some type of ancestral ape, he nevertheless recognized that humans were a very special kind of animal. In his book he wrote:

No one is more strongly convinced than I am of the vastness of the gulf between man and the brutes, for, he alone possesses the marvelous endowment of intelligible and rational speech [and] stands raised upon it as on a mountain top, far above the level of his humble fellows, and transfigured from his grosser nature by reflecting, here and there, a ray from the infinite source of truth.2

Continuity and discontinuity

It is worth noting that the problem of continuity versus breaks in the chain of life is one that both continues through to the present day and existed in pre-evolutionary scientific thought. The reason for this goes back to the intellectual upheavals of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The revolution wrought by Darwins work was, in fact, the second of two such intellectual upheavals within the history of Western philosophy.3 The first revolution occurred three centuries earlier, when Nicolaus Copernicus replaced the geocentric model of the universe with a heliocentric model ().

This pursuit known as natural philosophy positioned science and religion in close harmony. What linked them was the notion of design.4,5 The living world could be seen to be admirably efficient and well organized, with each organism playing a role for which it was well suited. This was taken as evidence for a remarkable design, and consequently as evidence for a designer in other words, the hand of God.

In addition to design, a second feature of Gods created world was a virtual continuum of form, from the lowest to the highest, with humans being near the very top, just a little lower than the angels. This continuum known as the Great Chain of Being was not a statement of dynamic relationships between organisms, reflecting historical connections and evolutionary derivations (). This focus on continuity, echoed in evolutionary ideas, was in fact one of the platforms on which Darwin built his theory. The difference between the pre-evolutionary idea of the Great Chain of Being and the later concept of an evolving lineage, though, is that the former was fixed. According to Stephen Jay Gould, the essence of the Chain of Being is the fixed positions of biological organisms in an ascending hierarchy.6

Next page