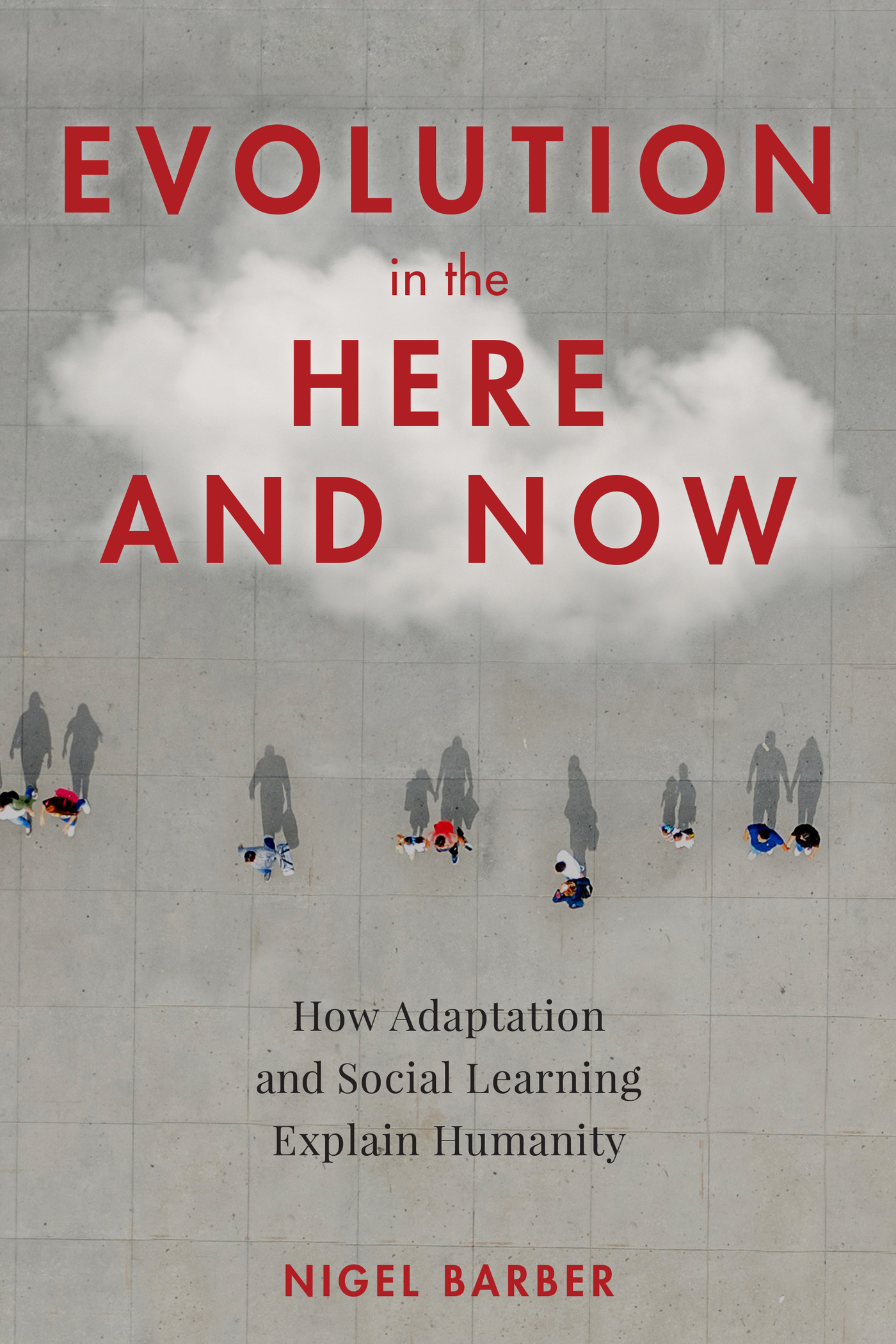

Evolution in the

Here and Now

How Adaptation and Social Learning Explain Humanity

Nigel Barber

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200

Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2020 by Nigel Barber

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 9781633886186 (cloth)

ISBN 9781633886193 (ebook)

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

To Trudy,

my wife, muse, soulmate, best friend, and champion

Introduction

This book introduces a new way of understanding the evolution of complex behavior for humans and other species. A skeptic might say that there is nothing new under the sun. There is always a grain of truth in that observation. Let me explain in broad strokes what is new here.

This book departs from the two main approaches to human behavior. The oldest is cultural determinism: maintaining that human societies differ due to socially transmitted ideas. This means that every society is arbitrarily different from others. Moreover, no human group is efficiently adapted to the way that they make their living or other features of the natural ecology. Being subject to internally driven cultural changes, human behavior is not predictable from the natural ecology in any but the most superficial ways, such as people who live in the Arctic making homes from snow and clothing from animal skins because these materials are available whereas wood and cotton are not.

Evolutionary psychology emerged as a revolt against the perceived arbitrariness of human behavior. If other species behave in ways that enhance their prospects of survival and reproduction, surely humansproducts of the same process of evolution by natural selectionwould do the same. Evolutionary psychologists emphasized adaptive patterns in behavior across most societies, such as men being more interested in physical attractiveness in a prospective spouse than women are, and women being more interested in the social status of a partner. They argued that such cross-culturally invariant patterns are evidence of Darwinian adaptation. Men are more interested in low-cost reproduction via casual sex whereas women need to ensure masculine investment in their offspring to have the best chance of raising them to maturity.

Although early evolutionary psychologists presented a refreshing challenge to the circularity and muddle of cultural determinism, their key claims were overstated. Gender differences that they assumed to be universal turned out to change over time. Gender differences in sexual psychology and behavior are disappearing in the modern world. This phenomenon pokes a hole in the argument that gender differences and other such cross-societal patterns are part of our genetic heritage and a product of gene-based adaptation.

Behavioral flexibility is not peculiar to humans. Many people fear snakes that could give fatal bitesat least for a few poisonous species. Fear of snakes is certainly powerful, but attributing it to our evolutionary history as hunter-gatherers may be a stretch. Indeed, fear of snakes in nonhuman primates is contingent on early experiences. If so, what humans fear may not be a consequence of atavistic experiences in hunter-gatherer societies. This impression is reinforced by remarkable research on the reaction of moose in North America to the reintroduction of wolves to their habitat after generations of extinction.

Initially, the moose showed no fear of their ancestral predators in a rather stunning disconfirmation of the idea that adaptive behavior is routinely transmitted via genes. Instead, moose acquired fear of wolves only after they were attacked. Young moose learned to fear the sight and scent of wolves by observing the impact of such stimuli upon their mothers. The notion that complex behavior, such as predator avoidance, is encoded in genes took a beating. Evolution is not restricted to genetic adaptation but works via learning and other mechanisms. In the end, natural selection has no preference for genes over learning. All that matters is whether the individual is successful in the current environment, not how their behavioral adaptation arose. The adaptiveness of moose reactions to their ancestral archpredators is really the consequence of their adjustment to the current environment. If so, then behavioral adaptation can occur in very short time scales rather than the millions of years it can take for anatomical adaptations to occur.

This impression is strongly confirmed by the novel antics of many species that share our habitat and have left the wild outdoors for city streets. In Thailand, long-tailed macaques happily use power lines as an elevated path over streets, as if they were jungle vines. They are skilled at stealing food from market stalls and even break into houses and steal from refrigerators. This means that they develop the capacity to eat scores of novel foods. In one of their weirdest adaptations to city life, they floss their teeth and use stolen strands of human hair as dental floss. These amusing novel behaviors were recounted by George McGavin in the British Broadcasting Corporation documentary series Monkey Planet. That these behaviors can emerge in a single generation in response to current opportunities shows how very far off the mark evolutionary psychologists were in assuming that adaptive behavior is genetically heritable and fixed.

The assumption that complex human behavioral propensities are encoded in genes is equally disputable. This is particularly true of gender differences in psychology that could only reside in the sex-determining Y-chromosome. Apart from initiating sex determination, the Y-chromosome does little that is functional, so any impact on gender-typed behavior would have to be quite indirect and therefore indeterminate.

If complex behavior cannot be genetically determined, then the entire tactic of using ancestral living conditions as a lodestone for identifying psychological adaptations is mistaken. Contrary to the views of early evolutionary psychologists, behavioral adaptations can occur on a very brief time scale. If moose become behaviorally adapted to new predator threats within a couple of generations, then human adaptive change must occur on a comparable time scale.

At such short time scales, genetic evolution is irrelevant given that this relies upon chance mutations that might crop up once in one hundred thousand years. Consequently, we must alter our definition of adaptations. These are no longer just gradual changes occurring over such slow time scales that are traced in the fossil record like the evolving leg bones of modern horses from tree-browsing ancestors.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.